Hirst’s flagship Tate Modern exhibition flounces on

Reviewing a Damien Hirst show is an awkward and tiresome task, because the two easiest arguments to make against him would mimic two of Hirst’s very own worst features.

It is possible to write an entirely negative review, as most critics tend to. The Evening Standard’s deeply respected Brian Sewell recently described Hirst as “polished shit”. However, this would add nothing to the general pool of ideas and simply repeat an already over-worked idea – much as the work of Damien Hirst does. Secondly, it would be possible to fawn over Hirst as a great modern artist and deeply scrutinise the themes of his work: life, death and the dualities of beauty and horror. This would imitate Hirst in an even more frustrating way. It is difficult, then, not to criticise Hirst without becoming a hypocrite.

Hirst is an excellent manufacturer of expensive products and an even more astute marketing man. Owning a Hirst could be seen as the same as owning an expensive piece of designer furniture. For the general populous (who are not the target market of his products), visiting his exhibition has the feel of an overpriced and disappointing amusement park. This is particularly true at the Tate Modern’s current exhibition in London, where dullish queues form around the most ghoulish exhibits, Mother and Child Divided and The In and Out of Love(aka The Cow Cut in Half and The Room Full of Butterflies).

The question is why Damien Hirst feels the need to constantly justify his repetitive and under-developed concepts. If Hirst were to admit art has become so interconnected with fashion and consumerism that this very fact can make for an interesting examination, many critics would have a lot more time for him. It would seem, though, that Damien Hirst at least believes in his own justifications and is incapable of seeing the recycled nature of his repeatedly reworked pieces. And it’s hardly surprising; what student artist has the income to construct giant tanks of formaldehyde? Hirst must have enjoyed a large following of very wealthy patrons in his early career. One can hardly blame him for having a warped self-image. Nothing like money to create a God complex, after all.

The Tate have succeeded in curating an exhibition that, in its organisation at least, seems to offer some view to the development of Damien Hirst’s career. Room 1 includes the first ever “spot painting” from 1986, followed up by a number of these mass-produced (most of these works are made by Hirst’s assistants) pieces throughout the exhibition. Rooms 2 and 3 astutely juxtapose Hirst’s pharmaceutical collections the Medicine Cabinets with A Thousand Years and The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

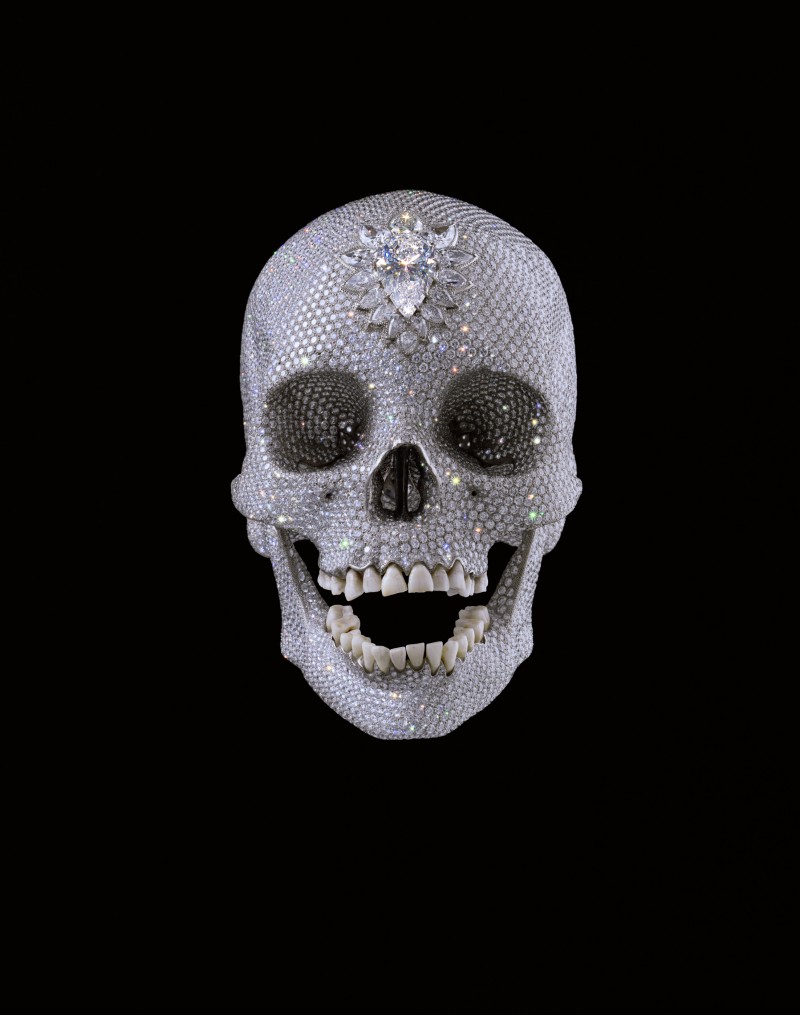

A Thousand Years is Hirst’s first vitrine work, in which the life-cycle of flies plays out from egg to maggot to fly to death, around a skinned cow’s head. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living is essentially a scaled-up, pricier version of The Kingdom – the first a great white, the second a tiger shark suspended in Hirst’s signature tanks, appropriately made specifically for advertising master-mind Charles Saatchi. So, medical science is a fallacy; we can’t escape death. We get it. As the exhibition goes on, The Anatomy of an Angelin Room 11 hints at this idea being extended to religion and by Room 13 the same point seems to be made sardonically about wealth (the first apparent nod from Hirst towards the vacuous nature of his own work).

However, there is so much sheer repetition throughout that it can’t be hidden away for long. Lullaby and Dead Ends Die Out mimic the exact processes of the spot paintings – the paradox of control in process to create an uncontrolled aesthetic. Like the sharks, Beautiful in My Mind Foreversimply injects expense to an identical process. Things lined up, things alive in tanks, things dead in tanks, spots. This has taken Hirst over 30 years to develop – it becomes easy to see where Sewell’s bitterness comes from.

Damien Hirst’s overblown justifications are all a part of the pitch. The fact of the matter is, his work sells and his shows sell out. Perhaps this is why his ideas, processes and aesthetic have been endlessly recycled since he was a student. Coca-Cola haven’t changed their packaging much since 1915, so why should Hirst?

Abigail Moss

Photos: Damien Hirst

Damien Hirst is at Tate Modern, London, from 4th April until 9th September 2012. For further information or to book visit the gallery’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS