Is the rise of UKIP symptomatic of an endemic problem with the British political system?

The recent Eastleigh by-election saw UKIP record their strongest ever result, finishing with a considerable 28% of the vote. With such a large number of people casting what is widely considered a protest vote, does this mark a crisis for the three main parties and the underlying system that they represent?

At Eastleigh, UKIP took advantage of the Government’s low approval rating, which, according to YouGov, shows 62% of people disapproved of their “record to date”.

Nationally, UKIP currently takes 12% of the vote in the latest YouGov poll, level with the Lib Dems. UKIP have been able to mobilise the support of right-wing voters, primarily based around the uniting dual issues of Europe and immigration.

But rather than being about the strength and appeal of UKIP as a party, what the result really shows is the weakness of the main parties, and the overall sense of dissatisfaction many voters feel with mainstream politics in general.

Indeed, according to a poll carried out immediately after the Eastleigh by-election, 75% of those asked said they voted for UKIP as a “general protest” – in effect meaning 21% of the overall vote was a protest vote.

Taken together with the 47% who did not vote, that amounts to a staggering 58% of all eligible people either did not vote or cast a protest vote – what you might call in political terms a sweeping majority.

Admittedly, by-election results are notoriously divergent from general election results. However, in the 2010 election the turnout was just 65%, the third lowest of all time, and it is estimated that less than half of people aged 18-34 voted. Something is clearly wrong.

This widespread disenfranchisement is often dismissed as apathy, but it is both inaccurate and unfair to suggest that people simply don’t care about politics. A study carried out by ex-GMTV presenter turned MP, Gloria De Piero, concluded: “[During the study] people wanted to talk about things that affect their lives, and they had lots of views”. Non-voters are often engaged with issues but feel excluded from the political process.

Trust in politicians is at an all-time low, due in no small part to the MPs’ expenses scandal and the incestuous relationship between sections of the Government and the media, revealed by the phone-hacking scandal. According to consumer group Which?, politicians are the least trusted profession.

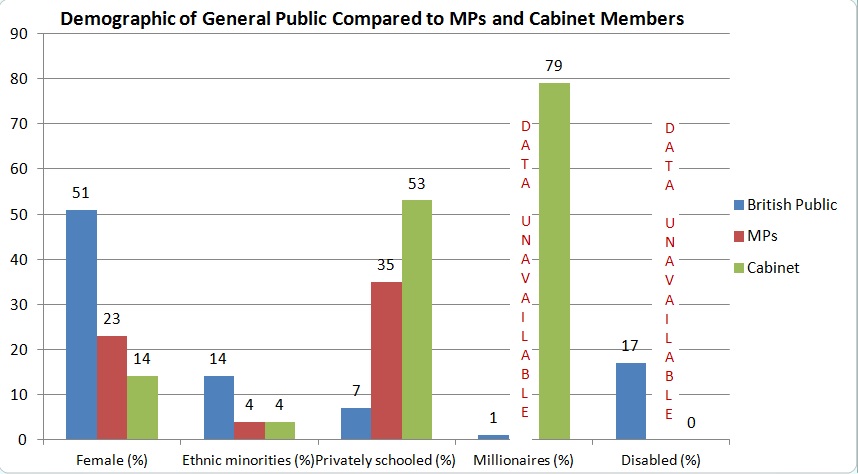

This chart illustrates the make-up of the general population compared to our MPs and cabinet ministers. Photo: Joe Turnbull

Whilst distrust of politicians is certainly nothing new, it is currently more pervasive than ever – in 1987 47% of people polled trusted the Government to “place the needs of the nation above the interest of their political party” – by 2010 this had plummeted to just 20%.

In a YouGov study people were asked “do politicians do a good job of understanding the daily lives of people like you?”, nine out of ten people said no. The fact is that politicians as a group are not representative of the general population in several crucial ways. This chart illustrates in percentage terms the make-up of MPs and cabinet ministers compared to that of the general populace.

If our democracy was truly representative you would expect each bar to be roughly similar in each category. But as you can see from the chart, there are some striking disparities. For instance, 79% of the cabinet are millionaires, whereas less than 1% of the British population are (there was no data for how many MPs are millionaires). Similarly, 23% of MPs and only 17% of the cabinet are women, compared to 51% of the population.

A measly 4% of MPs are from ethnic minority groups, whereas more than 14% of the population are. There are no statistics available for the number of politicians that are disabled, but the Government Equalities Office states that the number is “very low compared to the proportion of the population as a whole.” None of the cabinet is disabled compared to 17% of the population.

Politicians are supposed to represent the public – that is how a representative democracy works. But if politicians are completely unrepresentative of the population as a whole, and if the public have no faith that politicians are acting in their interests, then it really is no wonder that there is a crisis facing the British political system.

A seismic shift towards UKIP would do nothing to tackle these underlying problems and most voters are aware of this – remember, 75% of votes for UKIP are, after all, a “general protest”. Politicians need to be more accountable, more honest and much more representative of the electorate for the public to re-engage with mainstream politics.

Joe Turnbull

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS