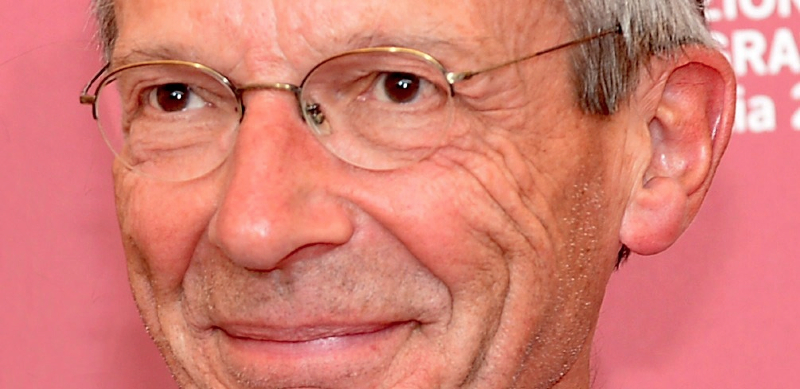

A Promise: An interview with Patrice Leconte

French director Patrice Leconte adapted Stefan Zweig’s novel Journey into the Past (Widerstand der Wirklichkeit) and for the first time has made a movie in English. Starring Rebecca Hall, Alan Rickman and Richard Madden, the picture tells a complicated love story that faces the challenge of time and distance separation in the Germany of early 20th century.

Why did you want to adapt Stefan Zweig’s novella?

Why did you want to adapt Stefan Zweig’s novella?

Jérôme Tonnerre, my friend and regular co-writer, recommended Journey into the Past to me because he thought certain of the subjects it deals with would interest me. Several days after I finished reading it I realised the story had stuck in my head. In fact I was deeply touched by the emotions, the feelings that it conveyed. I called Jérôme to tell him his recommendation had hit home and that I thought we should adapt it together with a view to making a film.

Are you particularly attracted to Zweig’s work?

Even though I love his work, he’s not a writer I keep by my bed, and I’d have never thought that I’d adapt one of his stories for the screen. Deciding to adapt a book is like half-opening a door: you see a possibility. And as with everything that’s happened during my career, my encounter with this book was both fortuitous and crucial – it echoed feelings that touched me particularly at the time.

What particularly interested you in this story?

It wasn’t so much a matter of knowing whether love can withstand the passing of time but rather whether desire can last beyond the years. There was something dizzying about this notion of declaring one’s love but swearing to belong to each other later. I found the fact that these characters experienced strong desire without telling each other very moving indeed.

Do you think holding back this way was linked to the period?

No, and anyway, I didn’t approach this subject like an historian. I projected myself as a man, I identified myself with the characters, I felt the emotion physically.

The film is set in Germany and begins in 1912, but we don’t perceive the tensions of the times so strongly. Was that deliberate?

Absolutely. Even though the film is set at a precise time in a precise place, I didn’t want World War I, which was brewing in 1912, to take over what seemed to me more important: the feelings that unite these two characters. They evolve in an emotional bubble that appears to anaesthetise them against outside events. But I didn’t invent anything since Zweig doesn’t depict any more of the beginnings of the war in his story than we do here.

Is your adaptation generally faithful to the novella?

Zweig’s spirit is there and the emotional issues are the same as in the book. But to adapt a work is to adopt it. You need to project yourself into it; you need to invent. Beyond the narrative ideas we had, the only remarkable adaptation we made was the ending. Zweig, being both a writer and a deeply pessimistic man (as his suicide proved), gave the novella an extremely disillusioned ending. In the book, when Charlotte and Friedrich meet again, they are like strangers. It’s winter, desire has faded away and their love has frozen. For the cinema, without wanting to have a happy end, we had to give their reunion a little bit of blue sky, a glimmer of hope for later.

What are the pleasures and the constraints of making a period film?

I didn’t have any problem with making a period film; while I like to remain precise, I always concentrate on the characters’ feelings, without allowing myself to be overwhelmed by too many details. What very quickly became clear to me was that in 1912 (and all the more so in Germany) women’s fashion was quite sad and not at all becoming. Their clothes covered their bodies entirely. To see a wrist, the nape of a neck, shoulders, not to mention a forearm or ankle – it was mission impossible! Yet since desire was the subject I both wanted and needed to see skin. But Pascaline Chavanne, the costume designer, quickly reassured me, telling me we could allow ourselves some freedom with the era without falling into anachronism or incongruous frills and flounces.

At first you wanted to shoot in Germany and in German. What made you change your mind?

At the very beginning I thought that a German language German co-production was the only way to adapt this book honorably. But I quickly realized that shooting in a language I didn’t speak at all was simply bizarre. Since shooting in French would have been absurd, my producers (Fidélité) suggested that I shoot in English with an Anglo-Saxon cast. The idea was very appealing; this universal language allows the story to be set in Germany while the characters speak English, without any problems.

How did you go about the casting?

Since my knowledge of British actors is not encyclopedic, I needed the help of a British casting director. I met a wonderful woman, Suzy Figgis, who works with Tim Burton, and with whom I really hit it off. She quickly suggested Rebecca Hall for the lead. I had only seen her in Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona.

I met her the first time I thought she was a bit “girl next door” and wasn’t sure she could be my Charlotte. But as always, the idea found its path. We saw each other again, she did some tests, and something magical happened. It was remarkable to see how this cheerful modern woman, who showed up on set in jogging pants, could transform herself. In costume, her hair done, and made-up, she became the character, with an intense sensitivity.

Richard Madden is a very young actor who has become famous through the successful series Game of Thrones. There’s something a bit wild about his character in the series; he has a beard. I kept asking myself if, once shaved, he would keep his appeal, if he would be able to portray this poor, young opportunist, crazy with love but extremely reserved, a Balzacian character utterly unlike what he has always done. But his enthusiasm and intense immersion in his work won me over.

Alan Rickman surprised me in a different way. Several people who had worked with him had told me he was a great actor but a complicated man. Nonetheless we understood each other very well and he trusted me. He was incredibly docile on set. His awareness of his character’s contradictory feelings allowed him to play him with much emotion and reserve. Watching him act, I had tears in my eyes. A talent that precise and precious is thrilling.

How did you direct them?

As I would French actors. With the same complicity, the same trust. But I did feel the pleasure they experienced being framed by the director. To film the actors myself is very precious in my work but strangely very few directors do their own framing. However actors adore this benevolent European sensitivity. Rebecca Hall – who had just finished shooting IronMan 3, a huge American machine where she was needed for five minutes a day to act against a green screen – was delighted. Just

like Alan Rickman who admitted to me that after two huge American productions he had slightly lost his taste for acting. When he hugged me at the end of the shoot and told me I had given him his taste for cinema back, it was better than if I had been awarded the legion of Honor!

Where did you film?

In Belgium. After a lot of location scouting, we found all the spots we needed for the film. The crew included my favorite collaborators but the majority – and far from the least – consisted of Belgians. It was a very pleasant shoot because it was very light- hearted. Everything was harmonious. The British actors were open-minded, available, trusting, focused on their work. I haven’t worked with the worst actors in France, far from it, but I’ve never seen such quality work. The weather was on our side, things went really well, as painters working direct to canvas would say. On this film, we truly enjoyed a little ‘state of grace’.

What did you want from the music?

I chose Gabriel Yared early on because I’ve very much wanted to work with him for some time. The challenge was to illustrate the feelings with much restraint, to be lyrical without falling into sentimentality. Pressing the accelerator and the brake at the same time wasn’t easy but it was captivating. His score is remarkable.

Was your recent experience with animation on The Suicide Shop useful in any way for this film?

If I change genre often it is to avoid taking the risk of falling asleep. But I can’t say that that experience helped me for this film, as it was such an entirely different area. What I do know is that it made me realize how much I love to shoot. I very much enjoyed making an animated movie, but I did miss being on set.

Is your wish to retire on hold for the moment?

I don’t know. For forty years I have always known what the next film would be, but I believe that this constant forward flight has finally started to make me feel dizzy. For the first time in my life, I’ve chosen to end a shoot without knowing what I will do next.

The editorial unit

For further information on the 70th Venice Film Festival visit here.

Follow our daily reports from the Venice Film Festival here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS