Hannah Höch at Whitechapel Gallery

Hannah Höch is not held in the esteem she should be. There are various reasons for this, and not one of them is the cliché that women get sold short by art history, true as that so often has been. Collage rarely gets the appreciation it deserves – even to this day – next to high art forms like painting, and Höch was a master of the collage.

Furthermore, Dada tends to rely either on the nonsensical or the abstruse – Höch is neither, she is shrewd, rational and precise. Had she been a man, she would have been sold short anyway. There is, from what other reviewers have written, a tendency to call her the first punk. If there is not truth in this then at least a justifiable explanation – namely that Höch handles issues that still have not been resolved. Her From an Ethnographic Museum, 1930 is a sharper look at racism, its cultural manifestations more intense than any being made today, in the age of post colonialism.

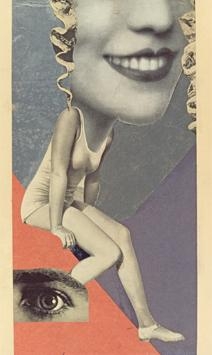

However, to compare her to the subject of Whitechapel Gallery’s last show, Sarah Lucas, is to find a more deadpan, ironical sensibility. Punk tends to touch on taboos like nerves; Höch tends to run a spike through them. Her Marlene of 1930 is a masterpiece of spectatorship, as is Little Sun of 1969. Readers will have noticed the gap, and it is one that the gallery is a little awkward about in turn.

Höch stayed in Germany during Nazi rule and kept herself to herself, in a cottage on the outskirts of Berlin. Her work rarely makes reference to what was going on during those years – those hunting the retrospective might find The Strong Man, 1931, and The Sea Snake, 1937 as direct references to those times. Needless to say, Höch was not exhibiting much.

Post-war she moved into abstraction, though keeping up with satirical collages, going now for Hollywood bombshells. Whitechapel Gallery has a problem reconciling these two sides of her work post-war – the show ends with Höch on film talking about the absolute beauty of abstraction – and then we are presented with work that is abreast with Rosenquist (try his Marilyn to her Marlene).

Höch, says the gallery, has never seemed more relevant. This too, is not true. Hoch is not “more relevant”; she has not been saved from Bluebeard the art historian’s tower, but is still unsurpassed. We still hold some of those old snobberies – while Höch was not being shown, Jenny Saville, super-pseud, was being lauded for doing certainly nothing radical, nothing short of reactionary in fact, but doing it in oil paint. There is the spectre of our new morality in calling Höch “never more relevant”, to which there is a simple antidote: imagine Höch’s works – Marlene, From an Ethongraphic Museum – made by a man.

Stephen Powell

Hannah Höch is at Whitechapel Gallery until 23rd March 2014. For further information visit the gallery’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS