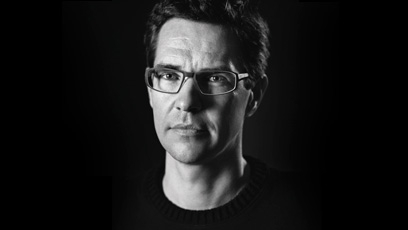

Cathedrals of Culture: An interview with Michael Madsen

We spoke with Michael Madsen, one of the directors of Cathedrals of Culture about his contribution, filmmaking and thoughts on criminality.

How were you invited to contribute to Cathedrals of Culture?

Michael Madsen: I was the first director to be asked if I wanted to participate, because the producers have seen my previous film Into Eternity, which had an architectural interest. They found out I have made a 3D film as well, and it seemed for them even more interesting. We had a meeting where I was pitched the idea and asked for my thoughts. They seemed to be thinking about concept-houses and museums, but I think there can be a wider interpretation to what is a cultural cathedral: in what sense is it an expression of culture in society? It was more interesting to look at a prison, because the prison in many ways is the flipside of the society. That’s where society ends; that’s where people cannot be in society anymore. I knew that my chosen prison in Norway was working perhaps to the highest degree in the world on rehabilitation. So that place, you can say, is an expression of how the state has decided to (ideally) bring its citizen back into society. The idea there is that the architecture, the interior design they chose, the colours and materials, the furniture – all of that contributes to making a better person, a better human being.

How did you research for the film?

I tried to be put into a prison and locked for several days, but that was not possible because in Norway, you’re not allowed to lock people unless they are criminals. I still needed to get some kind of understanding of what a prison is, so I conducted interviews with staff and prisoners to find out what kind of a place Halden is.

What, in your opinion, are the core values of Halden?

Time magazine claims Halden to be “the most humane” prison – and it is often criticised for being too humane. But the point is the justice system in Norway is not about revenge – it’s about rehabilitation. It’s much more valuable for both the individual person who goes to prison, and for society as a whole, that one can be re-integrated into society afterwards – that’s the idea. How does this rehabilitation technology actually work in terms of architecture was the quest of my film.

Do you hold personal opinion that a criminal should not be punished, but aided and helped to become a good person?

Yes, that is my personal opinion as well, very much so. I share it with the prison. One crucial point is that the staff also share the idea that dignity and respect are code-words in the interaction between them and the inmates. In the film, you will see that once you enter the prison, you are stripped naked and checked carefully throughout the whole body as to whether you are not hiding anything, and then put into a cell; but the guard also shakes hands with you and says “welcome”.

Halden is a modern prison, so it doesn’t look like a castle or a fortress – it looks almost as an old people’s solitude. The wall around it emulates a little village. Nevertheless, this is an institution of power, and there are rules for everything here – also for the things that there aren’t rules for.

It seems like the architecture is designed to hide the hierarchy and resemble a normal town as much as possible, but there is still an implicit hierarchy clearly felt and ever-present.

Yes, the challenge of hierarchy remains. Halden tries to emulate the surrounding society, or so-called normality inside its ward, and have a village-like structure so that even though you are imprisoned in one part of the town you go to work across to the other every day, you get education and so on. But still, only the guards have the keys that lock the door of your cell every evening. So there is someone who has absolute power – and you can’t remove that.

I remember getting the impression that it’s almost as if everyone were friends there: the guards interact with the inmates, eat together, etc. But of course, it’s only possible to a certain degree because at the end of the day, it is the guards who lock up the inmates, and not the other way around. And you can try to diminish that fact – but you can’t remove it.

Is this your personal opinion as well, or do you think that a self-sustaining prison with no higher power structures could ever be possible?

I don’t think that would be possible. To go as far as possible is saying “yes, this person has done something wrong – that’s why he is here. But what he did is not important anymore – now he’s here, and everybody is trying to get the best out of it” – I think that’s already an extremely powerful point. But it’s also clear that trying to pretend that there is no power or limits, or somebody who decides and others who decide nothing – to forget about that would be a mistake, because that would be another way of looking down on inmates. I don’t think that’s the case in Halden, but I suppose one has to be aware of that as well.

Now, a bit about your personal experience as a filmmaker, filming this prison in 3D. In what way does this new technology interest you? Do you think 3D is the future of the cinema?

I may be doing more films in 3D, and I think there are certain genres where it would be appropriate and interesting to use, like psychological horror films and thrillers. But turning to 3D with an interest of enhancing naturalism does not interest me. I think the more you can make a film play inside the viewers’ heads, the more interesting and richer film you can create. So if you use 3D for naturalistic or realistic purposes, then I think it’s artistically a dead end.

For the Cathedral series, 3D was appropriate because architecture is space; psychology is space. Architecture is not walls – it’s the space that’s created within the structures of a building. And that is a psychological space. That’s why when you are in some buildings, you like them. Perhaps you couldn’t say why, but there’s something about the dimensions, the layout that makes a difference compared to other spaces. It is very evident, it’s a sensibility that all humans have. So trying to render space for an architecture film – 3D is a sound choice.

Why are you interested in architecture?

Because it is a concrete manifestation of a society. A concert house is a concrete manifestation of certain ideals that a society may hold when this building is erected. In that sense, buildings are physical manifestations of, one could say, the best possible image that a society can hold of itself. That is also why for the series it was more interesting for me not to chose a celebration like a concert house or a museum, because I think that you may be able to see less truth about a society in such a building than if you went to look at the backside of it, in the form of a prison.

Ruta Buciunaite

Read our review of Cathedrals of Culture here.

Read more reviews from Berlin Film Festival here.

For further information about the festival, visit the official website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS