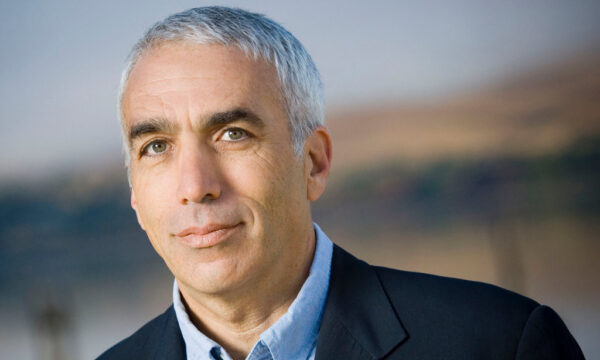

What Milo Saw: Virginia Macgregor talks about her beautiful debut

“As Milo shifted his head and focused in on the images through the small ‘O’ of his vision, he felt kind of lucky that he didn’t have to see it all.”

Berkshire writer Virginia Macgregor’s first mainstream novel is hot off the presses: What Milo Saw is the story of a nine-year-old whose vision is slowly fading, but whose heightened remaining senses allow him to see things others don’t. The author looks set for an illustrious career in British fiction; we got behind the scenes to ask her all about it.

What was your inspiration for What Milo Saw?

What was your inspiration for What Milo Saw?

I love old people: they’re warm, funny, quirky and full of stories and life experiences; they have so much to contribute. And yet, in the UK, we don’t value them and sometimes, sadly, we fail to care for them. I wanted to address this issue in my writing and when Milo Moon, my gorgeous 9-year-old protagonist, came along, I knew I had a character that could carry the weight of this story.

What challenges did you encounter during the writing process?

Writing What Milo Saw was a real joy – it’s a story that came from the heart and I had a wonderful time working on it. That’s a rare gift for a writer! The challenges were to get the various voices right. I wanted to create Milo’s world (a quirky nine-year-old boy with a degenerative eye condition) in a way that was believable and engaging. I also wanted to convey Gran’s voice (as someone who is very old and whose mind is slipping) with sensitivity and authenticity. Perhaps the greatest challenge was doing the edits when I was suffering from chronic morning sickness as I was pregnant with my first child, my little girl, Tennessee: it felt like writing on board a tiny sailing ship in the middle of a squall!

The relationship between Milo and his grandmother seems inverted in terms of care and responsibility – what led to this?

Some children carry the weight of the world on their shoulders, feel responsible, and want to help beyond what is natural for their age. Like Milo Moon. When Milo sees something is wrong, he sets out to put it right – and he’ll do just about anything for the person he loves most in the world, his grandmother. Milo senses that his mum, having been left by his dad, isn’t coping, so he steps into the breach. One of my aims as a writer is to convey the way we live now. Children all over the UK act as carers for their parents, their siblings and their grandparents. Milo is just one of many. I hope we’ll find a way to support them better.

Was there a message the book is intended to communicate?

Novelists are often wary of this question: they feel that their job is to entertain, not to convey messages. I believe there’s room for both. I want readers to enjoy What Milo Saw – to laugh and cry; to fall in love with Milo; to cheer for him; to hiss at Nurse Thornhill; to be desperate to find out what happens next – but I also want readers to become more sensitive to the world around them, especially to those who are struggling. To children who are losing their sight, to the elderly living in nursing homes that are failing in their duty of care, to refugees seeking to make their home in the UK, to single mothers left by their husbands… Novels should make us more compassionate human beings. If Milo goes some way in achieving that, I’ll be hugely proud.

What brought you to the split perspective narration structure?

It’s my favourite way of writing – my next novel also has multiple points of view. I find it thrilling to step into different shoes and to look at a story from different perspectives – and I think that readers enjoy this too. It’s a cliché to say that there’s more than one side to every story – but it’s true. We may feel cross at Sandy, Milo’s mum, for not being more understanding about Gran, but then, when we read a chapter from her point of view, we come to understand her struggles and how she’s doing what she thinks is right for Milo. I suppose it’s a democratic way of writing – of giving everyone a voice.

How was writing from the point of view of a sight-impaired protagonist?

Nerve-wracking. I wanted to get it right. As I wrote, I hoped that, if someone with Retinitis Pigmentosa read or heard my novel (there’s a wonderful audiobook of Milo), they would feel that their condition was accurately and sensitively depicted. So I did quite a bit of research. I joined discussion forums for people with RP, I quizzed my optician for ages, I read books. Besides the scary bit, it actually made the writing process more interesting as it allowed me to get closer to Milo: for every situation he found himself in, I had to work hard to imagine exactly what he saw, how he saw it, how he felt and responded to it. It made me love him even more!

Why did you choose to change genre from writing for children?

I spent a few years writing for teenagers because, having worked as a housemistress and English teacher, I felt I understood a bit about how they felt and saw the world. Teenagers get a bad press – I think they’re fabulous and I wanted to write novels with strong, interesting, teenage protagonists. My agent, Bryony Woods, signed me for my young adult novel set in a boarding school: When I Hold My Breath. Sadly, the YA wave seems to be ebbing – there’s much more focus on humorous middle grade (7-11) novels now. So I diversified and, as is so often the case when we try something new, I found my real home: writing novels for adults but with multiple narrators, including the voice of children. I do hope that When I Hold My Breath will find its way to the shelves… It’s a powerful story with a wonderfully plucky teenage narrator.

What writers would you consider inspirational or influential for you?

If you wanted to pay me a HUGE compliment, you’d say that I come half-way between Charles Dickens and Roald Dahl. Their characters are awesome and their stories, though very much grounded in the real world, also have a magical quality – I hope that you’ll find some of these ingredients in my novels. I’m also inspired by the international bestseller, Jodi Picoult, who tackles big contemporary issues through the lives of everyday characters. Emma Donoghue’s Room, narrated by a five-year-old child, is exceptional and gave me the courage to write from Milo’s perspective. Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible is one of the best multiple-point of view novels I’ve ever read. I could go on for ages but I imagine you want me to stop now.

What themes do you prefer writing on and why?

Human beings. Is that too broad? I love to write about ordinary people leading ordinary lives and to uncover how, in fact, they’re pretty exceptional. If we take the time to look closely at just about anyone, we’ll be blown away by how fascinating and bonkers and funny and amazing they are. More specifically, I’m fascinated by the tricky dynamics of family life and of how, when our blood relatives fall short – or are absent – we create new families for ourselves. That’s the theme of my next novel! Beyond this, I like to tackle “now” issues, problems that define the times in which we live: a shocking news item on the nursing home crisis in the UK triggered my idea for the plot of What Milo Saw.

What are your plans for the future?

I’m editing book two, which, though not a sequel, is very much in the same style as Milo: multiple narrators, one of them a child, another quirky animal, a powerful family story, a novel that addresses contemporary issues. I’m also working on a memoir of my mother’s life. With her identical twin sister she hitch-hiked through the twentieth century, fleeing the Russians in Berlin, sailing to America on a cargo ship, living with Quakers whilst dancing to Elvis, taking part in the student riots in Paris, meeting Salvadore Allende in Chile before he was assassinated… I grew up with these stories and now it’s time to write them down!

Francesca Laidlaw

What Milo Saw is published by Sphere at the hardback price of £14.99, for further information visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS