Venice Film Festival 2014: Interview with 3 Hearts director Benoit Jacquot

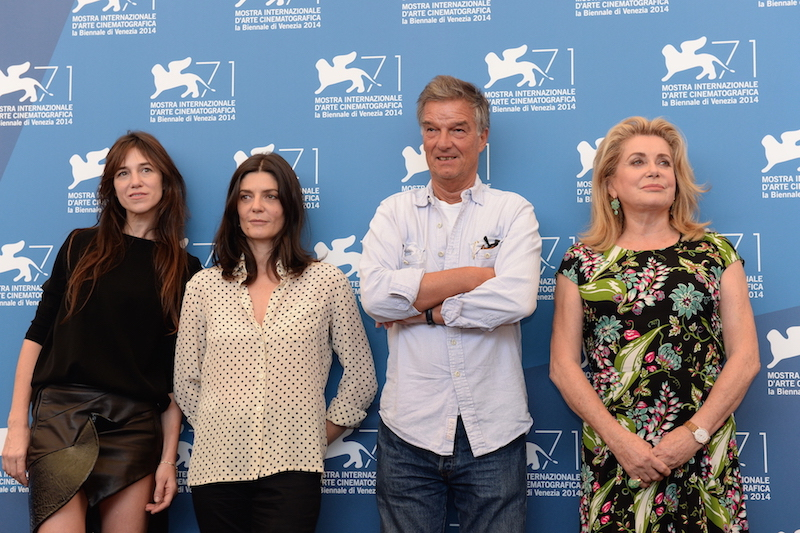

Presented at the Venice Film Festival 2014, 3 Hearts stars Benoit Poelvoorde and the three fantastic actresses Chiara Mastroianni, Charlotte Gainsbourg and Catherine Deneuve. This is what director Benoit Jacquot had to say about the movie.

How did the screenplay of 3 Hearts come about?

As always when I write an original screenplay, there was a combination of desires: after a number of costume films, I needed to make something more contemporary, a film that took place in the here and now. And after having abundantly focused all my last features on female characters, I felt a need to deal with a male character, if only to make sure I could do it. My cinema is mostly tied in to female figures. I wanted to test myself on another ground.

You hadn’t done it since Sade.

Yes, but Daniel Auteuil quickly realized I was at least as interested in the character played by Isild Le Besco. He made the most of it, the very most, in fact: the role interested him even more.

Let’s get back to the origin of 3 Hearts.

I wanted to shoot a story that took place in the provinces, a mid-sized town that had a southern feel. The French provinces are conducive to developing a melodramatic argument: I specifically wanted to deal with a man grappling with a secret romance.

Because he missed a meeting with Sylvie, with whom he fell in love (Charlotte Gainsbourg), Marc (Benoit Poelvoorde) ends up marrying Sophie (Chiara Mastroianni) without knowing she is the sister of the girl he’d fallen for head over heels.

I had long been interested in studying the particular effect two sisters might have on a plot. Marc loves one and then the other, in different but intense ways. Only the audience knows it and that’s what creates the melodramatic tension. Together with Julien Boivent, my accomplice in writing Villa Amalia and Deep in the Woods, we tried to bring all these elements together. A man misses his train in a provincial town, he meets a woman, they don’t tell each other anything about themselves in a sort of game. They agree to meet again, and like in any self-respecting melodrama, miss their appointment. The story can begin.

I had long been interested in studying the particular effect two sisters might have on a plot. Marc loves one and then the other, in different but intense ways. Only the audience knows it and that’s what creates the melodramatic tension. Together with Julien Boivent, my accomplice in writing Villa Amalia and Deep in the Woods, we tried to bring all these elements together. A man misses his train in a provincial town, he meets a woman, they don’t tell each other anything about themselves in a sort of game. They agree to meet again, and like in any self-respecting melodrama, miss their appointment. The story can begin.

Marc misses the meeting because of a heart attack.

3 Hearts is about the heart in the literal sense. I was interested in the idea of seeing a character suffer physically because of a heart problem – the opportunity to show the heart as an organ.

There is real magnetism involved in Marc’s meetings with Sylvie and then with Sophie.

I like romantic encounters that start like that, with a simple gaze – an instant that acts like a spark between protagonists. There’s a lot of poetry in that scene: as in the moment for instance, when Marc gives his age by walking by a house number.

That really happened to me. All my original screenplays are full of coincidences like that – those signs that the surrealists relished and that seem to make room for chance between lovers.

Sylvie immediately dumps her boyfriend, as does Sophie a little bit later. As does Marc, when he realizes he can’t live without Sylvie. The characters in the film behave radically.

I have the feeling that women always behave that way when they leave a man. Personally, that’s how I’ve always been dumped. Love doesn’t wait, it proceeds at its own pace.

In 3 Hearts there are extremely rapid, almost brutal movements, and others on the contrary that are very serene, like the scene in which Marc’s character suddenly feels happy in his marriage, almost forgetting the other woman in his heart.

The story, which brings literally extraordinary moments into play (romantic encounters are the only ones that warrant that term), had to be set in the most ordinary, normal environment possible. Regarding that passage, I emphasize this new happiness Marc experiences at that point in his life in voice-over: he has decided to live a normal life, but it’s not abnegation. Except that there is something buried within him that bears Sylvie’s face and is waiting for its moment.

And that moment constantly appears and disappears with amazing completeness and transience.

And that moment constantly appears and disappears with amazing completeness and transience.

Charlotte Gainsbourg is like that: she slips away. She occupies space and time in a very special way, but you get the feeling she could vanish in an instant. Her presence is like an apparition. There’s something powerful and evanescent about it. True charm in the strong sense of the word.

3 Hearts plays with literary time.

It is the heart’s time. It doesn’t obey the usual calendar and breaks the classic rules of narration. In 3 Hearts there are leaps in time, sometimes several years, and present times that on the contrary can be very detailed.

Is there an influence from the operas you’ve been staging over the past ten years or so?

I would say rather that I practice understatement. Opera has allowed me to shed a certain restraint, to cross barriers that I had placed up until then with respect to physical expression and the formulation of feelings. In opera the music and the singing carry you away in a very specific, almost brutal way. I realize today that it has had an effect on my filmmaking. It’s not by chance that the subject matter of 3 Hearts is melodramatic.

You’ve always been very fond of the great American melodramas.

That passion remains intact. While writing the screenplay for the film, I had in mind John Stahl’s Back Street, Leo McCarey’s Love Affair and An Affair to Remember, and Douglas Sirk’s movies. But opera awakened in me what stirred me when I watched them.

3 Hearts can be watched like a melodrama, but it can also be described as a sentimental thriller.

Absolutely. A film isn’t powerful and doesn’t really work unless its genre is forgotten. At no point during the shooting of 3 Hearts did I say to myself: “Let’s make it a melodrama.” I couldn’t have done that. It would have been a sign that something was wrong. Sure, the film describes a melodramatic situation, but in my own way.

Each of your films seems to be taking a new risk.

Even if I constantly shot the same thing over and over again, like hammering away at the same nail, I would still feel the same anxiety. My movies are like experimental protocols: the same experiment goes on, the protocols change and any new opportunity is welcome.

Do you mean tackling a central male character is part of a new protocol?

How do you film a man when you have the reputation of filming women, and beyond that, of spending your life with the actresses you film? Could my cinema accommodate the presence of a male actor? I was indeed curious to see if it would work and how it would work.

Did you have Benoit Poelvoorde in mind from the start for Marc?

Not right off. My first idea was for an actor friend but he and I both realized very quickly that our closeness was likely to get in the way. We had already done two films together, and I had the impression – maybe wrongly so – that I’d know beforehand what he would do. Working with someone I didn’t know afforded me the freedom to discover other emotions. And discovering things in the cinema is to invent them.

Who was the actor that impressed me the most today? The one I liked the most and with whom I would most like to do a film? Benoit was an obvious choice, and I knew through his agent – who is also mine – that he too wanted to work with me.

How did things go with him on the set?

How did things go with him on the set?

There’s always an unknown aspect about Benoit’s way of acting and being. What is he going to do? What state is he going to be in: exuberant or on the contrary totally depressed? Even his use of language is unusual, at once very articulate and very digressive. You never know what leg you’ll be standing on when you film Benoit.

Why did you make his character a tax inspector who on top of it glorifies his profession?

Because I’ve met some of them and they are fascinating people. An old friend of mine, an art dealer, once went through a long and complicated tax audit. The two tax inspectors in charge of it were a couple, and on top of it, became his best friends. Tax inspectors run into more types of human beings than police detectives: they are excellent judges of character. They interfere in people’s private lives in an entirely legal fashion and they have to have intuition.

It’s finally through a mirror Sylvie had bought at an auction that ends up in the home of the newlyweds that Marc enters into communion with the one he loves.

The mirror plays an important role – it’s almost a device of fantasy films. Sylvie fell in love with the piece, bought it and placed it in her shop. In a way, the mirror retains her image; it holds on to her. Having the piece at home, Marc lives with Sylvie’s spirit.

There’s a tragic dimension to this secret couple. Even though she loves her sister and she tells herself she’d die if Sophie found out about her betrayal, Sylvie yields to passion…

They’re living a Racinian tragedy. On the set, I often told Benoit: “Racine, think about Racine.” It’s a little like the “Alas, alas…” at the end of Bérénice: a scarcely audible melody, unfathomable and tragic.

Charlotte Gainsbourg and Chiara Mastroianni are amazingly credible in the roles of the two sisters.

Because they both totally believed in the story. I immediately had Charlotte in mind when I was writing 3 Hearts. Among the few great French actresses, she is one of the ones I like the most and with whom I’d never yet worked. Chiara came later because for a long time I thought that Sophie, her character, should be younger than Sylvie. Charlotte was thrilled when I mentioned Chiara. She totally agreed.

This sort of part is very unusual for her… She gives the film a very romantic and incredibly fleeting dimension.

It surely has to do with the way she is, very frank and up front. Paradoxically it suggests at the same time a secret and unresolved side, even to herself. Chiara is one of those actors who surrender to their characters as if trying to understand their own mystery. It lends their acting a very intimate tone; a rather unique touch of truth. I really like that sort of actor: I know they’ll astonish me.

In 3 Hearts, you are working again with Catherine Deneuve with whom you did Princesse Marie in 2003, about Marie Bonaparte’s relationship with Freud.

I knew Catherine well before this shoot but that wonderful experience we shared abroad during the three months of filming meant that we would work together again.

The problem remained of finding the right role for her, and I admit that without Edouard Weil, the film’s producer, I probably wouldn’t have had the guts to offer her this character, which is theoretically not a central one. Catherine agreed right off the bat.

On the set, she was not only the mother who played hostess to her two daughters and this guy, Marc, at home; she was not only the actress filmed with her partners. For the whole cast and crew, and for me, she truly became the “lady of the house” working with the property person on designing menus, the cooking – there are a number of meals scenes in the film. In this hostess role she found a freedom that allowed her acting great subtlety, making her role decisive. In 3 Hearts her glances, her way of being there and intervening, her tone of voice and rhythm are decisive and that helps the others find their roles. Charlotte, Chiara and Benoit were totally impressed by Catherine…

Given that each of the four actors have a movie past, the meal scenes have particular resonance.

It’s a tradition in French cinema: when meal scenes are good, they’re really good. Meals in Sautet’s films, to mention him alone, are really fantastic. When you shoot them, it’s almost like you were filming archive footage documenting actors in the process of acting and on the period in which the scene takes place: how people eat, how they interact. As to the fact that the cast carries with them a movie past, I’d say instead that I trust their characters to make me forget it. But the romantic dimension is there, undeniably. How many French actresses have had a career like Catherine Deneuve? I can only name three: Jeanne Moreau, Isabelle Huppert and her. All three of them are walking cinematheques! Every film with that sort of actress practically guarantees there will be more to come. It’s almost a necessity.

Catherine Deneuve’s character as well as the one played by André Marcon, a local government official, cast a light on the sentimental situation of the three heroes that could almost replace the camera lens: they are both acutely aware of what is going on before their eyes.

No matter what situation they find themselves in, I like the protagonists in my films to be intelligent, I like them to have such sharpness about themselves and others that at no point can you think they’re idiots. For instance, it’s not because the audience knows the situation Marc is struggling with that they feel smarter than him: they see Marc blinded and finally destroyed by the situation he got himself into, but they still don’t have an answer to it.

As is often the case in your films, the outdoors, gardens and forests occupy a special place.

Just as it’s very important to me that the characters find the right actors, I like scenes to find the right places.

You show Versailles in Farewell, My Queen, you show the Tuileries Gardens in 3 Hearts. Do you film a period movie the same way as you film a contemporary movie?

I certainly don’t say to myself that I’ll film it differently. The distances, the types of approach and the angles aren’t necessarily the same. The light isn’t the same in the 18th century and the 21st century, nor is the way of dressing – and undressing. But I’ve always made sure that even when my films took place in a bygone era they remain as modern as possible. Despite that, I absolutely wanted 3 Hearts to be grounded in the present day, with all the outer signs of the present.

Why shoot that final meeting in the Tuileries at the end of the film?

The scene is directly inspired by Back Street. The hero is at home surrounded by his children who forbid him from seeing the woman he’s been having an affair with for the past 30 years. He is on the phone with her, he’s dying of a heart attack – heartbreak? – he puts a positive spin on the fact that they missed their rendezvous and because of that never married. It’s heart-breaking.

The editorial unit

Read all our Venice Film Festival 2014 reviews and interviews here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS