Under Electric Clouds: An interview with director Aleksey German Jr

Under Electric Clouds, the fourth feature length film of Russian director Aleksey German Jr, premiered at the Berlin Film Festival 2015 in the competition category. We sit down for a chat with the director for unique insight into the film and the current political climate in Russia.

More than ever in recent years, there is a real impetus around contemporary Russian film, such as Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan and your Under Electric Clouds, can you explain what is going on right now?

Russia is happening to Russia. It’s a very different country, not only about alcoholism and small towns, but also big cities and contemporary art museums, people being very rich, the current crisis, corruption, the intelligentsia, imperial ideas and also about paranoia. For 300 years, Russia has been questioning itself about where to go, and it still hasn’t figured it out. It’s about historical circles, repeating and repeating themselves over and over again.

To put it simply, Russia is going through a very imperial period right now. It’s difficult and a very long story, but the tragedy of Russia is that it’s neither Asia, nor Europe; it’s somewhere in the middle. 20 years ago, Russia wanted to be a part of Europe, but for various reasons that didn’t happen. What we have now is a country trying to prove itself. I don’t know why this is. For sure, it would have been better if it had become a NATO member in 1999 and the EU as well, but they didn’t want us.

The way you portray Russia is quite desperate, but is that representative only of Russia, or of other European countries as well?

I know Russian culture better than European culture. That’s clear. To me it seems that to try to be artistic anywhere can be a rather sad business, and that living artistically is better when left in its own format rather than in the real world. We live in such a stigmatised society, and it’s difficult to do something different, something higher than you are. This is true everywhere, not only in Russia; but in Russia, it’s perhaps a little more difficult.

I know Russian culture better than European culture. That’s clear. To me it seems that to try to be artistic anywhere can be a rather sad business, and that living artistically is better when left in its own format rather than in the real world. We live in such a stigmatised society, and it’s difficult to do something different, something higher than you are. This is true everywhere, not only in Russia; but in Russia, it’s perhaps a little more difficult.

In the film, you lay special emphasis on those people who belong to the intelligentsia. How do you see the role of this group today?

Now the intelligentsia has very much split. It doesn’t seem possible, but they’re still talking about things on the internet which they were arguing about in articles in the 19th century. In the last year they haven’t decided on anything. This is for various reasons, but one of them is that the intelligentsia has lost a lot of power because of too much infighting.

How do you feel about the near future of Russia?

It’s difficult to speak about Russia alone. You need to, for example, speak about Russia and America. It’s going to become more and more about weapons, and neither side is backing down about defence. I think we’re entering more and more into a cold war situation, and Russia has this paranoia which is getting bigger. It has been invaded so many times, and it’s afraid of being invaded again. Russia is so afraid of its borders, even those far away. Talking about the Ukraine, I would call it a historical paranoia. I would like to say something different but I can’t. It’s not possible for it to be a democratic path for Russia, because people in Russia are contending too much to be able to come to an agreement.

Your previous movie was set in the Soviet Union, Under Electric Clouds is set in 2017, exactly 100 years after the Russian Revolution. Is there a kind of nostalgia, not necessarily for the regime, but for the nation that Russia was at that time?

In 1917, Russia was already no longer a great country, and I wouldn’t say that there is any kind of nostalgia about some kind of greatness from imperial times. What is very important for the protagonists in my film is the feeling of a dying or melting away of culture. In the film, it’s very important to categorise time, because I think that time in Russia doesn’t develop in a linear way. It goes backwards and forwards, constantly changing direction. The remaining nostalgia that there is, it’s nostalgia about some kind of possibility of a unity of thinking people. We had this at the end of [the Soviet period in] the 80s, even in the beginning of the 90s, and then everything started to fall apart.

Can you say something about the general colour of the movie, the cinematography, and the quote from Cezanne at the opening?

Can you say something about the general colour of the movie, the cinematography, and the quote from Cezanne at the opening?

Impressionism for me is very important, and we tried to go in this direction very much with this film. Film is a very visual art, and we tried to find visuals which corresponded to the idea of how impressionism visualises the world. I shot my first film in black and white, a kind of half-documentary, but I think that this sort of realistic thing doesn’t interest me anymore.

Your film is a Russian-Ukrainian-Polish production. Considering the current political crisis between Russia and Ukraine, were you under any conflicting pressures from either country while making the film?

We were shooting for a long time in Ukraine before the war started, and we tried to keep it this way without too much attention. Afterwards we started shooting in Saint Petersburg. There is a certain tension towards the film in Ukraine and in Russia as well. Today is a hysterical time in Russia. You can be accused of being a foreign agent, and you could also expect a similar reaction from Ukraine.

A few of the characters unexpectedly speak foreign languages, and foreign products are frequently mentioned. Is this supposed to represent something more than just the idea of internationalism, but of cultural globalisation?

Of course! You go in your backyard and you see lots of immigrants from different countries. We have a huge ethnical diversity in Russia at the moment, and I think it is good, but still the situation is that builders are always immigrants. This image of Russia consisting of huge, blonde people, it’s an odd picture.

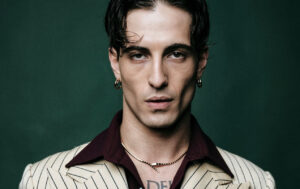

Rosie Boys

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Berlin Film Festival 2015 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS