Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the NY Society Library

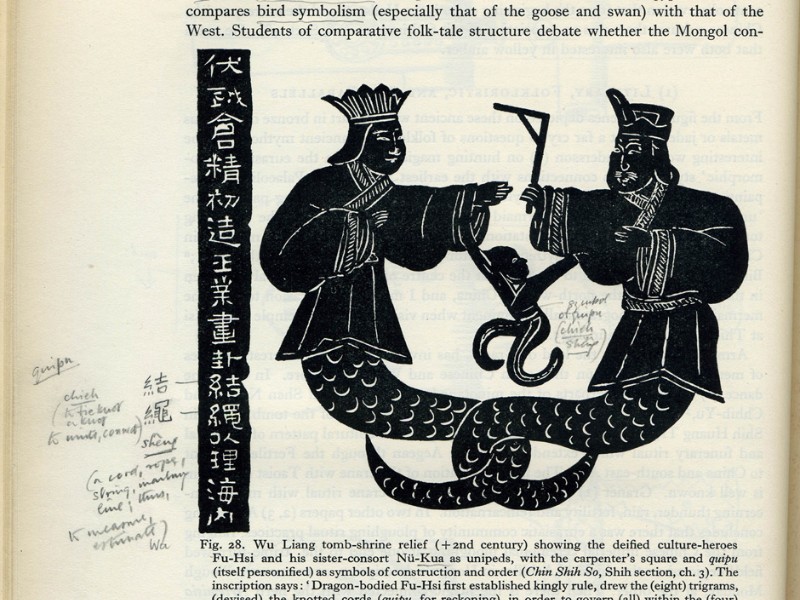

There’s still something vaguely illicit about scribbling in the margins of books – a kind of literary graffiti where the public space is between text and binding. It’s only recently that this stigma has started to lift, with annotations being allotted the same critical eye given to content just a few millimeters on the right. One of the forerunners for this new approach is the New York Society Library, with their current exhibition Readers Make Their Mark, which focuses on such handwritten comments bordering the texts of their collections. The exhibit asks us to redefine the standard definitions of author and reader, as the latter can’t exactly be considered passive upon seeing their annotated interactions with the text.

One of the co-curators Erin Schreiner shares her thoughts and findings with us on these “renegade” footnotes, and why they deserve our attention.

What was the “genesis” story for this exhibit? Annotations have become increasingly popular, but what was the development and curating process for Readers Make Their Mark?

In June of 2013, I wrote this blog post about Anthony Grafton and Daniel Rosenberg’s Cartographies of Time – an illustrated history of the timeline – and illustrated my post with an annotated chronology by Heinricus Pantaleon from the John Sharp Collection. Somehow, the post made its way to Grafton and Rosenberg, who contacted me to find out more about chronologies and annotated books in the Society Library’s collections. Grafton was a fellow at the Cullman Center at New York Public Library in the 2013-2014 academic year, and in the fall he organized a trip to the Society Library with a group of Princeton students that included my co-curators, Frederic Clark and Madeline McMahon. The group spent a full day in our reading room with about fifty annotated books from our collections, including the Pantaleon that he had seen in my blog post. After the visit, I contacted McMahon and Clark with the idea of co-curating an exhibition based on that day’s work. They said yes, and we moved forward from there. In early spring of 2014, Clark, McMahon, and I dug through the NYSL collections, discovering rich new veins for exploration (especially in the Winthrop and Sharaff/Sze Collections) and planned the scope and organization of books on display.

Annotations can show how popular thoughts morph and adapt over the years (i.e. between Adam and John Winthrop). Any specific examples you can think of in trends of thought?

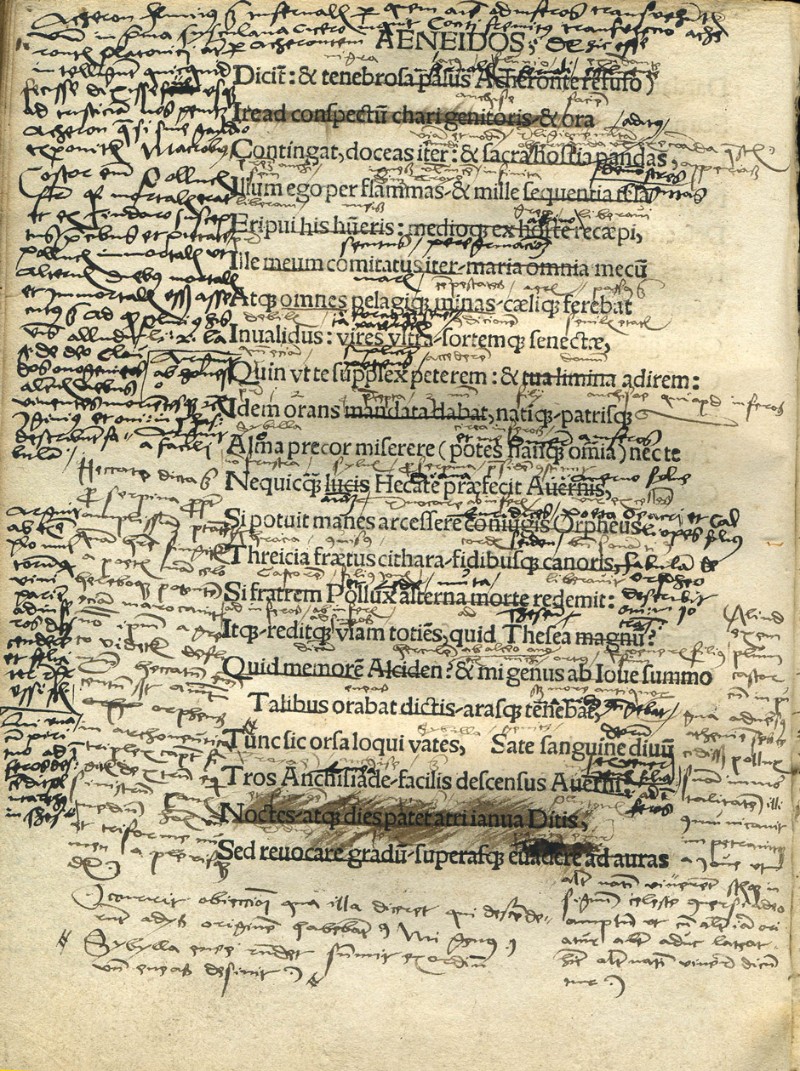

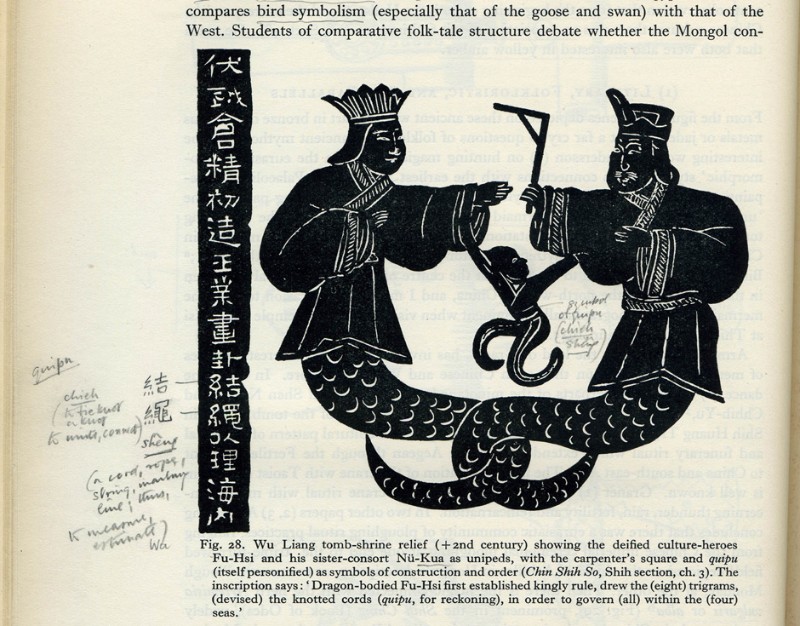

I think that one of the most interesting things that come to light in this exhibition is the continuity in annotating practices. The cases are organised to reflect this: people annotated as they read in order to respond to texts with commentary or criticism; to remember what they read; to revise what they’ve written or correct others’ mistakes; and as part of the practice of scholarly research. Despite remarkable disparities across time, space, and culture, there are remarkable similarities in the reading/writing practices of Mai-mai Sze and the Winthrop family. Both engage with difficult books covering a variety of spiritual, philosophical, and material subjects. As annotators, Sze and the Winthrops work through difficult texts in a variety of languages by cross-referencing other sources, creating their own indexes, and making careful notes on the authors whose books they study. These readers lived in totally different worlds, and came from astonishingly different backgrounds, and yet the way that they approached their books were remarkably similar.

Why are annotations important/worth studying?

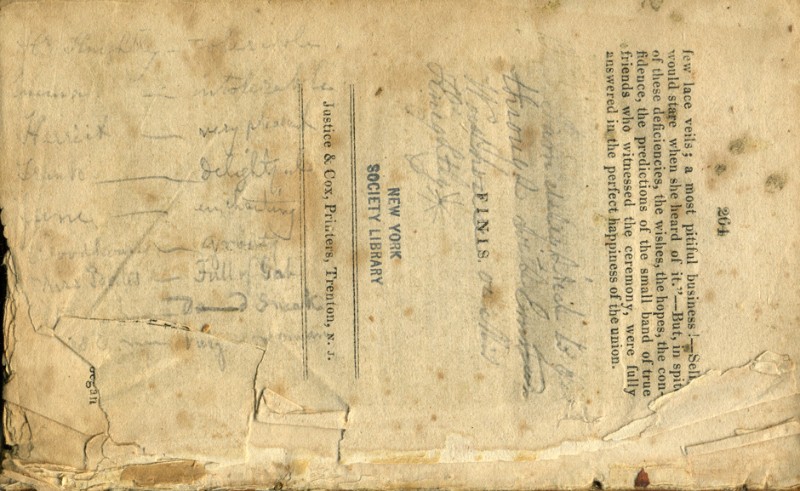

Annotations are worth studying because they are the only physical remnants of an incredibly private practice. Readers’ experiences with particular texts can tell us a lot about who they were (or are), how they lived, and the way they related to the written word in all of its forms: fiction, poetry, non-fiction. Particularly as we come to terms with new media, I think it’s important to look back to reading practices of the past to see how people adapted to new technologies and incorporated them into their learning lives, and how those technologies have changed the way we create and share knowledge. Annotations provide us with an extreme close-up of the individual reader at work, and that can be interesting whether or not the person is a well-known individual with a celebrated body of creative or scholarly work.

On a more personal note, it’s exciting and inspiring to look so closely at another person’s reading practice. There is some voyeuristic pleasure in studying annotations – and that comes with all of the consequences and complications of voyeurism – and having access to someone else’s learning and thinking processes. Annotations can serve as a main line to the reader’s humanity. We can see, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly, the questions that drive them to read more, reaching farther and farther into an ever-expanding galaxy of resources.

What about the annotations that don’t necessarily add to the “conversation” of the text? Are they equally important?

I think that annotations that are not in direct conversation with the text can be important or at least informative, but that depends upon the eye of the beholder. At the very least, such marks in books (or even unintended marks or artifacts like food stains, animal paw prints, pieces of hair or grass) provide evidence of reading. I think it’s safe to say that all of us own books that we have never read, so knowing that a person interacted with a book enough to have something even uninspiring to say about it tells us something. These kinds of marks can tell us a lot, also, about the book as an object people lived with. For example, John Winthrop Jr used a blank leaf in his copy of Aelian’s Variae Historiae to sketch a view of London Bridge during a visit to the city. This might not tell us much about what Winthrop thought about Aelian, but it does tell us something about Winthrop’s whereabouts, his interests outside of the text, and his access to paper at that moment in time.

As readers do we have an obligation to contribute to the texts we study?

As I think this exhibition clearly shows, annotation is a very personal process. It’s something that readers on display mostly did when they were intensely engaged with the text (or texts) in hand. I do not think we’re obliged to mark up the books we read because I don’t think we engage with every book with the same level of intensity. But reading and writing relate much like dancing and music: one complements the other, the experience of reading enriches the experience of writing and vice versa. I think that people build interesting and complex relationships with books as objects, and annotating is one way to do that. Are all of us required to build such relationships with our books? Certainly not. Does it make things more interesting when we do? Yes, indeed.

Kelly Kirwan

Photos: New York Society Library

Readers Make Their Mark is open to the public at the New York Society Library until August 1st 2015. For further information on the New York Society Library visit here, for further information on the exhibit visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS