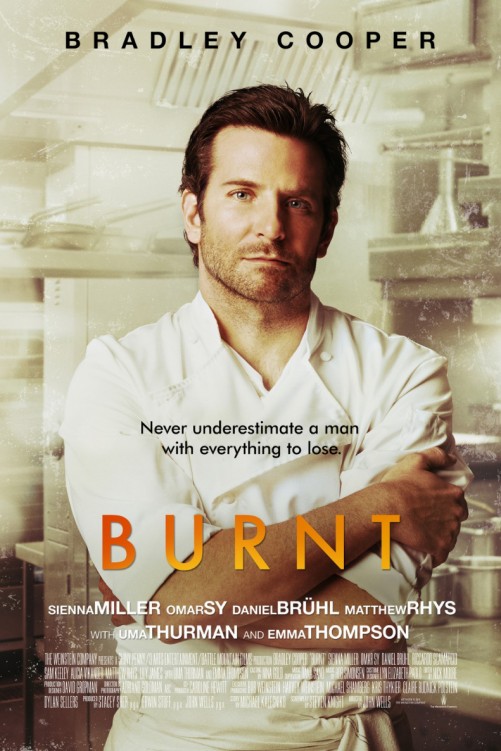

Burnt

To add to the recent surge of fine-dining films, Burnt contributes a sense of arrogance and badassery to the genre, rather than finesse and taste. It’s difficult not to assume the influence Gordon Ramsay had to the food-culture phenomenon, with shows like Hell’s Kitchen and Kitchen Nightmares running rampant. Bradley Cooper’s solid and aggressive performance delivers homage to these dramatic and antagonising chefs rather than to the brilliant cuisine they produce.

Cooper as Adam Jones, a brilliant – yet troubled – chef seeking his third Michelin star, emerges as the rock star of fine dining: fallen from grace and seeking redemption. After his disappearance, or rather banishment from the Parisian culinary scene due to his own self-abuse, he strives to tackle the London culinary world with the aid of his old maitre d’ confidant Tony (Daniel Brühl) and single-mum sous chef Helene (Sienna Miller).

Directed by John Wells and written by Steven Knight – with the help of Marcus Wareing as culinary consultant – the film does well to capture the reality of a Michelin-star kitchen with close ups of igniting blue flames, sizzling proteins on a cast-iron skillet, and beautifully plated dishes. However, the film does not capture the reality of the man behind the food. Jones is portrayed as an arrogant, violent, unstable character, and somehow his contemptible behaviour is forgiven because of his culinary brilliance. This plotline tends to become cliché and predictable and doesn’t credit the hard work and love that goes into making truly brilliant food. Here, the film becomes less about the chemistry of molecular gastronomy or innovative cooking techniques, and more about the chemistry between humans.

Rather than focusing on the substance, the food, Wells’s film turns its attention to human imperfection, leaving the cuisine underdone and lacking in flavour. With the food playing a supporting role, Cooper and his cast mates highlighted strength of human intensity and determination, and the restaurant business served as a cultural metaphor. The relationship between Cooper and Brühl conveyed the teamwork of the chef and maitre d’: the chef delivering artistry and beauty, the maitre d’ providing precision and presentation to create the magical dining experience. Scenes of the produce and ingredients in their raw, natural state reminded the audience of the integrity of the product, and the labour, care and respect needed to create “culinary orgasms” – as Jones puts it.

Burnt narrates and derives from the “food porn” culture that has emerged over the last few years, which is similar to the level of filmmaking: mouth-watering, but dissatisfying.

Dominique Perrett

Burnt is released nationwide on 6th November 2015

Watch the trailer for Burnt here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS