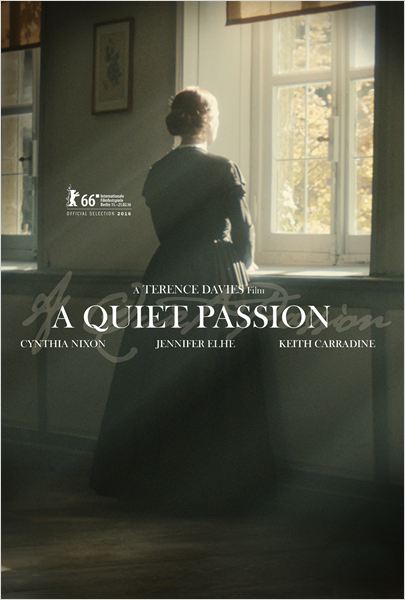

A Quiet Passion

At its Berlinale premiere, the only comment director Terence Davies allowed himself to make about his newest film was a characteristically self-deprecating one: that it was evidence of his talent for depicting “misery and death”. Its subject, the poet Emily Dickinson, may well have had similar thoughts about her own work in her darker moments. But the statement, though contestable on the surface, would be inaccurate for both. Rather, what Davies and Dickinson both achieve is a profound understanding of the at times symbiotic relationship between agony and ecstasy, in life and in art.

The Emily Dickinson depicted in A Quiet Passion (first by Emma Bell, then by Cynthia Nixon) is marked out from the beginning by her defiance, with her teenage defence of the sovereignty of her soul against a stern seminary lecturer forming only the first of many debates. Her ideas and opinions are given eloquent expression throughout Davies’ script, which allows Dickinson ample opportunity to confront the prevailing puritanism of her day and its concurrent marginalisation of women.

The assuredness that Dickinson demonstrates in Davies’ dialogue – which often sparkles with Austenian wit – finds a perfect counterpoint in her poetry, which reveals the vulnerability and uncertainty Dickinson steadfastly refuses to betray in public. Few filmmakers understand the spoken word in the way that Davies does, and his previous adaptations of Edith Wharton and Virginia Woolf for film and radio demonstrate his particular affinity for the work of women writers. Thus, as in her life, Dickinson’s poetry becomes an ever-present part of the film, whether woven into casual conversation or crafted into sublime set pieces. In Davies’ hands, it becomes “the poetry of the everyday”.

In the end, the objects of Dickinson’s quiet passions are manifold: her family, her friends, her writing, her ideals, and the dream of consummate love, which she ultimately foregoes. But, throughout the film, it becomes clear that her greatest passion is for honesty. At a time when women had (as she points out) little more to aspire to than decorousness, she consistently wages war with her opinions, maintaining her beliefs against the tyrannical intolerance of polite society. This dedication to telling the truth has also marked the most personal of Terence Davies’ films. In this respect above all, filmmaker and subject have rarely been better matched.

Marc David Jacobs

A Quiet Passion does not yet have an official UK release date.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Berlin Film Festival 2016 visit here.

Watch a clip from A Quiet Passion here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS