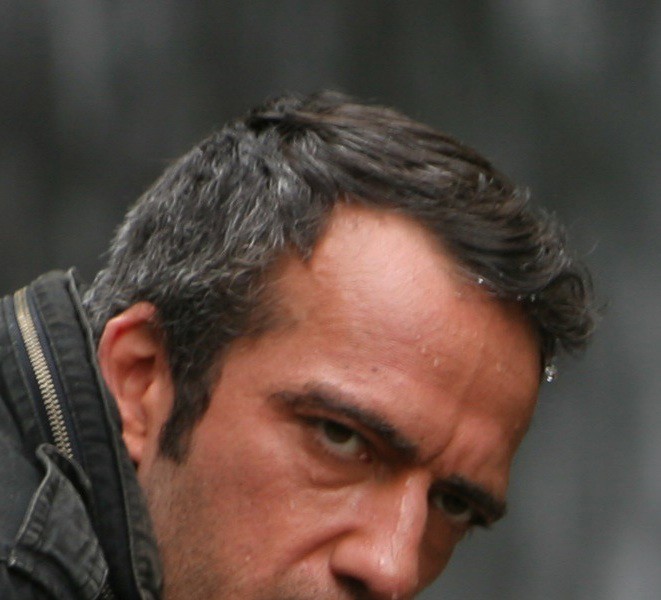

Berlin Film Festival 2016: Rafi Pitts: An interview with the director of Soy Nero (I Am Nero)

Hailing from Iran and now living in France, director Rafi Pitts has made his first English language film with Soy Nero (I Am Nero). Depicting a little-known aspect of life for young people who grew up in the US (but who were not in fact legally permitted to be there), the film shows how joining the US military as a Green Card Soldier (also known as the DREAM Act) can be a path to citizenship. This method is not always successful, and a number of undocumented young people found themselves deported after serving in the US military – something that infuriates Pitts. We spoke to him, just after his film premiered at the 66th Berlin Film Festival, about what made him want to tell this story, and how he hoped it would give actual Green Card Soldiers and their families a sense of pride.

You’re Iranian, and the film tells the story of a Mexican hoping to build a better life in the US. The themes are universal, and yet elements of the story are very specific to the US and Mexico. What made you want to tell their story?

I wanted to make a film about No Man’s Land. I relate to No Man’s Land and to me, America is this No Man’s Land. America doesn’t have a nationality because it belongs to the world. It’s a country of immigrants. There’s not a single nationality that you could say is truly American apart from the Native American Indians, and these people are not in charge of America. The Green Card Soldiers are fascinating: there are Iranian Green Card Soldiers, and there are German Green Card Soldiers – they come from all over the world. So here you have an army without a nation, and a nation without a country, if you will. And the juxtaposition of these two things is, for me, the story that needed to be told. It doesn’t pinpoint an issue. If I had chosen, say, an Iranian Green Card soldier, the world would be saying that the film is about the Iranian-American relationship. People simplify everything and I didn’t want that to happen. It’s about the humanist point of view that I have. The world is aware of American culture, the world is aware of the need to belong, and the world is aware of immigration. The problem is that it’s happening all over the place, but we’re more clear than that country (the US), which is building walls. They’re not letting people into a country that belonged to them not so long ago. California belonged to Mexico not all that long ago really.

Have you shown the film to any of the DREAM Act soldiers, those who served in the US military in an attempt to become a legal resident, as Nero does in your film?

I plan to screen the film in Tijuana, Mexico, right next to the wall that faces America, just to give a sense of pride for the people in Tijuana who helped (with the movie) and also the Green Card Soldiers, many of whom are from there. So the first screening we do in Mexico will be on the beach there. It’s important, but one thing I should clarify about the DREAM Act is that it only passed in congress for California, so it’s actually called the California DREAM Act. The other states haven’t passed it yet. So this is why it concerns Mexicans more than other nationalities. They were the largest number of people being deported after 9/11.

The film is critical of the DREAM Act and yet it acknowledges that it can give hope to someone in Nero’s situation. What do you think about the Green Card Soldier scheme?

These days we are living in an absurd world moving at a very fast speed, and like here we are, you weren’t even born when the first Green Card Soldiers were deported. You are unaware of it, of these Green Card Soldiers. I’m not a visionary person, but as a filmmaker it’s a very complicated thing. I’m very upset with humanity, and it doesn’t make sense in a world that keeps saying people need to integrate. When politicians make very big speeches, I find it inadmissible that these things exist. It became one of the big influences in the film: the very title of the DREAM Act. I want to find a picture of the guy who came up with it so I could ask him a simple question: “Why did you call this law the DREAM Act?” A dream is something with hope, and here you are giving this to someone you are throwing out of the country, and you’re saying, “Oh, but we have the DREAM Act… if you go and fight for us.” Why they call it the DREAM Act I don’t know.

Do you find it strange that a story depicting Green Card Soldiers hadn’t been told before your film?

It’s crazy because these Green Card Soldiers have existed for a very long time – since the Vietnam War. This is why I don’t understand it. Whether you are American or not, it’s got nothing to do with your political beliefs. There’s an angle to tell a story, and to find something unique in this film, so that when it comes to war you can say something new. Why is it that I haven’t seen an American war film where at least one of the characters is a Green Card Soldier? They have been in the Army for so long, and some of them were then deported. Is everybody blind? Because I went there and I saw these deported people in the camps. They are very young men and they have been thrown out. You wonder why there haven’t been ten documentaries about this.

Oliver Johnston

Read our review of Soy Nero here.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Berlin Film Festival 2016 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS