Mothering Sunday by Graham Swift

In the wash basins of the World War I the red socks of modernism were thrown in with the starched whites of mainstream thought with the result that everything went a little pink. By the 1920s, recent experiences had cast widespread doubt about the assumptions and the institutions of the past: how could we trust authority when it was authority that had sent the boys to the front? How could we pretend that art represented reality when all around were the fantastical echoes of trench warfare? It became clear for many that things would never be the same.

In fact, one couldn’t even be entirely sure which “things” there were. As Jane Fairchild, the central character in Graham Swift’s new novella puts it, the war was “so like another world that trying to remember it was a bit like writing a novel.” But in a way, this was true of everything, or at least became true at some point. For Jane it came to a head on Mothering Sunday, 1924.

Raised an orphan, she is put into service with a family in Berkshire where she falls in love with the princely Paul Sheringham, next door, one year her senior. The two begin a clandestine affair that is to last seven years until the soon-to-be-married Paul calls on Jane for one last day together. She had always taken care to hide her bicycle in the shrubs and to take the back path when he calls, but his instructions that day are different: “11 o’clock. Front door.” It is Mothering Sunday, the day the staff are free to visit their parents – if they had any of course – but not Jane. Today he has the house to himself. Today it is the front door.

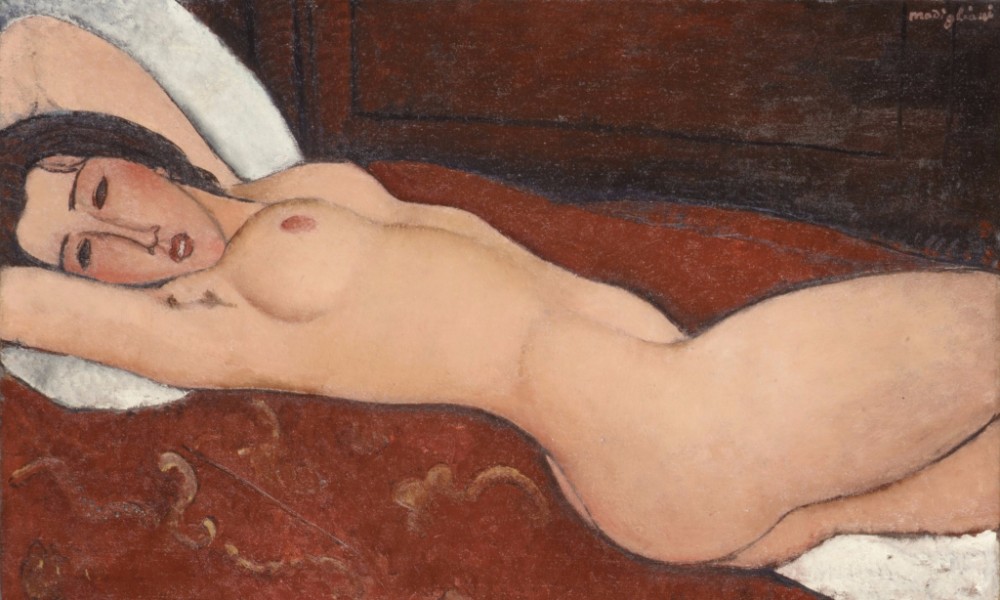

Mothering Sunday was already an outdated occasion by this time in history, a relic to match the clothes and lifestyles of those that clung to it; but as Jane follows her lover into the house, the clothes come off, and with them the ideas that had structured their past. She is divorced from her uniform, literally and figuratively, and born again into a world of narrative and construction, where a maid isn’t a maid but merely a woman who works as one.

Though it is, at its core, an ironic book, a self-conscious romance out to discredit itself, it is also deeply moving. And despite his occasional gracelessness (“She didn’t move – she didn’t know how long she didn’t move – until it seemed the absurdity of her not moving won out against some dreadful need not to. Then she moved.”) Swift’s little book is exquisitely thoughtful, subtle, and expertly told. It might be his best work yet.

P B Craik

Mothering Sunday is published by Scribner for the hardback price of £12.99, for further information visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS