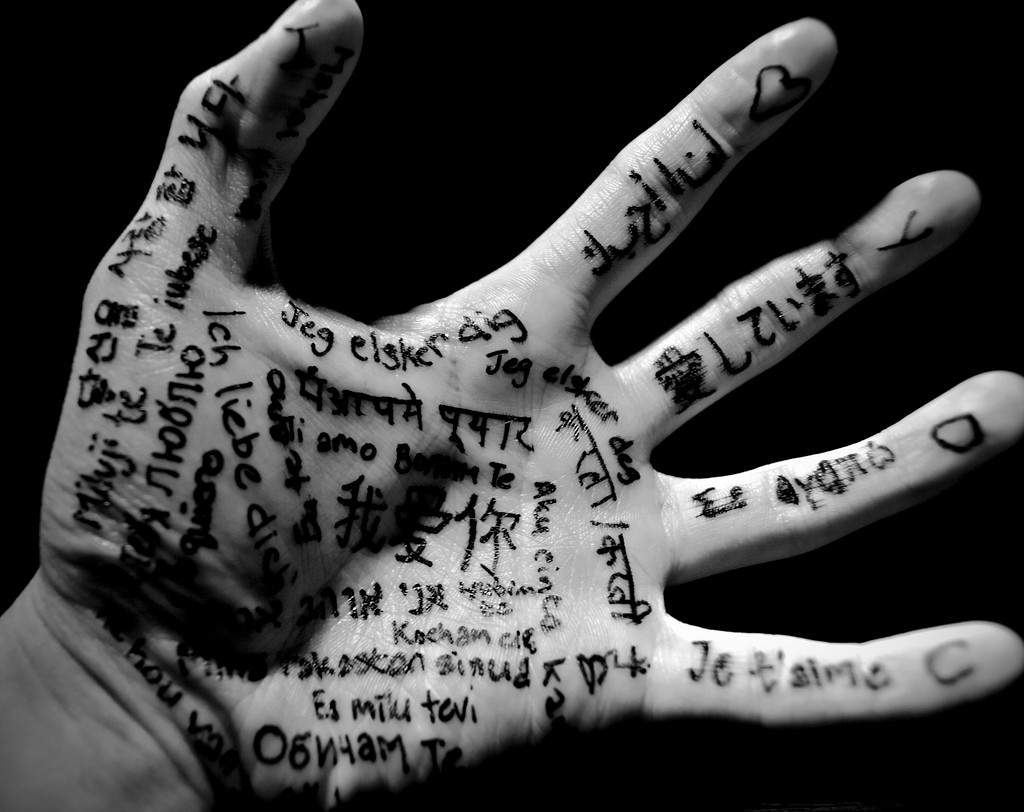

Does language change the way we see our surroundings?

The neurological benefits of knowing more than one language have long been touted by medical professionals. As well as improving general understanding and cognitive skills, research has also shown that it can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by up to four years. However, a recent study by John Hopkins University in Baltimore has shown how, as your language recognition skills develop, so too does your general perception of your physical surroundings.

The study tested two groups of 25 people – half experts in Arabic, half new to the language – to identify differences between the pairs of characters. The results showed that, while the novices were speedier at telling the letters apart, the experts were not only more precise but could identify more complex characters more quickly. One of the researchers on the project noted that “What we find should hold true for any sort of object — cars, birds, faces. Expertise matters… you know what to look for.”

Language and perception – a special relationship

Many linguists have pointed out the way the traits of certain languages can change a culture’s lifestyle. For example, certain native Australian languages refer to compass points – north-east and south-west for example – instead of left and right; this has apparently improved the spatial awareness of these Aboriginal tribes, particularly concerning directions.

This also applies to the way we see colours: while in English we have words for single colours, and additional words to describe brightness and shade, other languages have individual words to differentiate. For example, in Greek, there is a specific word for dark blue (ghalazio) and for light blue (ble) rather than a single word for “blue”.

English eccentricities and ambiguities

Even in English, the use of words in a certain context can impact how we view and comprehend situations. As reported by Slate, one test asked people to read an article each about an increase in crime; in one article, the crime was described as a “beast”, and a “virus” in the other. 71% of test subjects who read the “beast” article felt more should be done to improve the crime situation, whereas only 54% felt the same when reading the “virus” article. The researchers behind this study noted that this is likely due to the connotations of the words: “In the best case, people say… the kinds of things that you would imagine doing for a real beast… for a virus people come up with more preventative solutions.”

Similarly, the Wall Street Journal points out that English seems to be a language all too eager to assign blame and responsibility. While the construction of Japanese or Spanish sentences would lead to a phrase like “the coffee spilt itself,” English syntax insists that a person needs to be grammatically identified as the cause of action. This has impacted on the relative ability of speakers of different languages to actually remember who is responsible for these sorts of incidents. When it comes to English, the article suggests that this particular quirk of the language can directly affect “what [people] remember as eyewitnesses and how much they blame and punish others.”

The editorial unit

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS