Ophelias Zimmer at the Royal Court Theatre

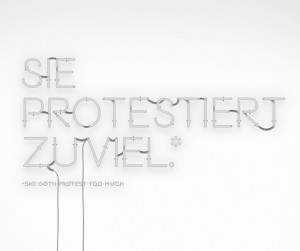

Freeing the character from the limitations of Shakespeare’s original text, Ophelias Zimmer takes a frank look at the ways in which the narrative of Hamlet shapes Ophelia’s existence and reinforces the traditional gender stereotypes that continue to pervade our culture.

Whilst Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead may appear the most obvious touchstone in terms of concept, Alice Birch’s script shares far more thematically with the likes of Sarah Kane’s brittle, brutal bibliography and Samuel Beckett’s looping Krapp’s Last Tape. Chloe Lamford’s set, meanwhile, has the grim austerity of a prison or institution and Max Pappenhelm’s ambient sound design, mixed with earthy Foley artistry, is like an aural ghost story.

All of this coalesces under Katie Mitchell’s masterful direction. Ophelia is stuck in a near-endless routine of emptiness dictated by others, the punishing portrayal of which becomes increasingly hypnotic as the play goes on. With Cleansed at the National Theatre Mitchell drew criticism for the numbing nature of the constant violence. The patience Ophelias Zimmer displays, however, means that those moments that punctuate the cyclical action take on an almost unbearable intensity.

Arguably the most memorable instance is also the play’s most comic, as Hamlet bursts into Ophelia’s room and performs an epileptic dance to Joy Division’s Love Will Tear Us Apart. What initially appears absurd becomes more and more distressing as Ophelia’s face remains frozen in a grimace of anguish. And it is no accident that such a clichéd choice of song is used. It reveals Hamlet to be a stunted, volatile example of a certain kind of toxic masculinity, who treats Ophelia as an object of obsession instead of a human with any agency of her own.

In a near-speechless role (in German with English surtitles), Jenny Konig’s performance as Ophelia is mesmerising. Konig manages a delicacy that is startling, her face a canvas for suppressed panic and pain to dance across. She is haunted by the disembodied voice of her dead mother, who repeatedly urges her to “smile”, while being trapped in a world that barely exists beyond the four walls of her room. Just as radical is Birch’s treatment of Hamlet, which explodes the idea of the character as a brooding, tortured anti-hero by showing him through Ophelia’s eyes. He is a sexually aggressive, grotesquely recognisable combination of adolescent and adult, silencing Ophelia through his complete disregard for her boundaries.

The play becomes increasingly queasy as it gradually moves towards its unavoidable crescendo. Yet, the inevitably of the ending is subverted by an act that poses a direct challenge to the ambiguity of Ophelia’s death in Hamlet, in the process forcing the theatre to face some of the unsavoury aspects of Shakespeare’s legacy.

Connor Campbell

Ophelias Zimmer is on at the Royal Court Theatre from 17th until 21st May 2016, for further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS