Ross & Rachel: An interview with playwright James Fritz

After a very successful run at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2015, playwright James Fritz’s production of Ross & Rachel is ready to hit the London stage in June. The play is unusual in that it consists of only one performer, the talented Molly Vevers, and tells an eye-opening story about modern relationships, shedding a harsh light on our understanding of “happily-ever-after”. We spoke to James about his motivations behind the play and its title, his casting decisions and his views on the relationship between pop culture and theatre.

What made you decide to use Ross and Rachel’s relationship from Friends as the archetype of the stereotypically troubled modern relationship that your play addresses?

I think I could’ve picked a lot of titles for the play, but those three words have become a kind of pop cultural shorthand for a certain type of relationship. You hear people say things like “they’re hardly Ross and Rachel” all the time. I saw two characters in Game of Thrones being jokingly referred to as “the Ross and Rachel” of the series just the other day. So even if you’ve never seen an episode of Friends you know what sort of relationship those words represent.

What made you decide that the play should be a one-woman duologue, instead of using two actors?

Having a single body on stage is such a massive choice and I like shows that make that choice for a reason. I felt that with this it was a great way of exploring that idea of a relationship being “two halves of the same whole” and what that does to the identity of the characters. I was really interested in what happened to an audience’s reading of those identities when they share a body and a voice with very little to differentiate them.

Were you ever worried that, upon hearing the title of your new play, people would immediately assume it was actually based on the Friends series and not an original work of your own?

Maybe a bit, but I also think that’s fine. It’s fantastic that people bring their own pop culture experiences and expectations into the room. Whether the play works with or against those expectations, it creates an interesting tension either way.

What do you think it is that has made the stereotypical “love story” such a recycled concept throughout literary history, one that keeps people coming back to it again and again?

I think it’s a really satisfying narrative and one that we can all relate to. Love is one of the strongest emotions we can feel, and so many people have felt that strongly about another person. But we also like to believe in it as a catch-all solution to life’s problems. The idea of the “thunderbolt” is a bit like winning the lottery – it implies a lifetime of happiness when the reality is often much more of a mixed bag.

Considering Ross & Rachel has only one person performing in it, it must have been very important to cast the right actress. Was this difficult and what exactly were you looking for in the right performer?

It was massively important, and for that reason we saw a lot of people for the role. With Molly we were incredibly lucky to find someone who found her own fascinating way through the challenges that the text posed, who could play both characters while still keeping herself really present in the room. I think the play’s most interesting when you’re aware of the performance, of there being three people on stage – the two characters and the actor channelling them. It’s a tough job, but Molly does it wonderfully. I love watching her performance every time – it changes so much, and is definitely the major reason why people should come and see the show.

Were there any other rom-coms that particularly inspired you to write the play or influenced your characters?

Yeah lots. I used that title but the show and its development were influenced by all manner of romantic sources. There are as many references to tragic traditional love stories as there are to modern rom-coms, I think. Love Actually and other Richard Curtis movies were a big touchstone, as were Titanic, Jerry Maguire, Pretty in Pink, Twilight, When Harry Met Sally, Pretty Woman and The Holiday. And the end of Grease. Loads of films that I really enjoy: all of which have people doing strange and problematic things all in the name of love.

I was really struck by the end of How I Met Your Mother a couple of years ago. The show spent ten years moving away from its original proposition of Ted and Robin getting together, actually doing the impossible and introducing a new “mother” character in a way that made us care about her. And then, right at the end, they undid all that good work and threw Ted and Robin together again because that’s how they’d decided things should end. We can’t help but embrace the idea of destiny winning out, even if it makes no narrative sense.

How did you find your way into your current career? Has the theatre always been an area you wanted to work in or have you written for other mediums too, such a film or TV?

I was in my school play and decided I wanted to act. Then I got to university and realised I was a dreadful actor so I started to write. I wrote comedy sketches mostly at first, and then started trying to write longer things for theatre. I did an MA at Central which was incredibly important to my development as it gave me a year to think about what writing was and what sort of writer I wanted to be. I then worked hard for quite a few years writing short plays and longer, terrible plays that were really good practice and I’m very glad never saw the light of day.

I’ve started to dip my toe in TV waters, but theatre’s what I love and the thing I most want to focus on. I find it a fascinating process, and there’s nothing I love more than watching my words as part of a live performance that I’ve helped make with a bunch of other people. It’s such a weird, wonderful experience.

How has it been working alongside your director, Thomas Martin, and producer to bring Ross & Rachel to life? Do you have any advice for other playwrights about working in theatre production?

It’s been so rewarding. I’ve known both for years and the chance to get to work together on something like this has been such a wonderful process. It’s been an incredible and rare experience because I’ve been able to develop this play right from the beginning with both producer and director involved. The play went through a lot of development before it got to production and my name might be on the front cover but it feels like something by all three of us. I think we often give writers too much credit in British theatre. So many people help shape the script into what it is and yet it’s mine that ends up being the only name on the front cover of the play text.

The way we write about dramaturgy and direction can be far too simplistic – Tom’s directed “the show” but he’s also been shaping the text since I first put pen to paper. It’s been incredibly collaborative, and any writers out there looking for someone to work with should track down his email and pester him. He’s a really talented dramaturg, and without him this play would have been terrible.

My advice to playwrights starting out would be to open yourself up to other people’s input. Theatre is a team sport – you’re making something that is going to be worked on with loads of other people, so there’s no point working in a vacuum. Find people you trust and make things together. They will only make you better, not worse. And try to work with your mates, because there’s nobody better to share these experiences with.

What do you think about the current place of pop culture in today’s society and the effects it has on modern writing and directing?

I think the more it finds its way into the theatre in different ways the better. It’s such a wonderful shared shorthand we all have with each other, and thanks to the internet and meme culture has never been more important to the way we communicate. Theatre is a place of communion, so it seems churlish to leave something that unites so many of us at the door.

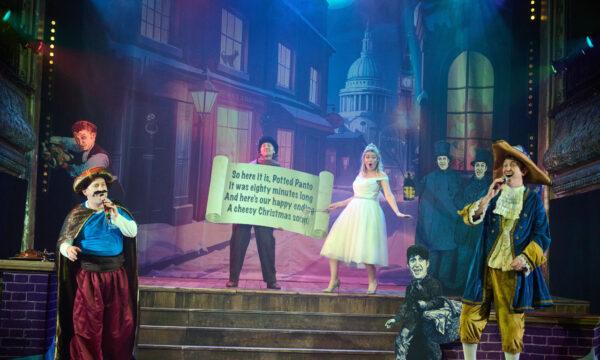

I think one of the reasons pantomime is the most popular form of theatre in the UK is because it has always played on this shared sense of cultural knowledge. Everybody goes and can enjoy a reference to the town mayor, or the local butcher, or a celeb from TV. It’s inclusive. It’s thrilling to see productions at all kinds of theatres now embracing pop culture and bringing an audience together in interesting ways.

What do you hope audiences will take away from Ross & Rachel? Is there an important message you hope to convey through the play?

I hope they’ll all take away lots of different thoughts about lots of different things. The reactions we’ve had so far have been wonderfully varied. I hope that continues.

Jo Rogers

Ross & Rachel is on at Battersea Arts Centre from 21st until 25th June 2016, for further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS