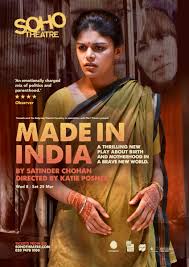

Made in India: An Interview with playwright Satinder Chohan

Satinder Chohan is a journalist and documentary researcher and producer turned playwright, from Southall, West London. Her plays include Zameen (Kali Theatre national tour 2008), Kabaddi Kabaddi Kabaddi (Pursued by a Bear national tour 2012), 1984 (Vibrant Festival 2014 Finborough Theatre) and Lotus Beauty, shortlisted for the 2016 Sultan Padamsee Award for Playwriting. In 2013, she received Off West End’s Adopt a Playwright Award to develop Made in India, which explores the issues surrounding commercial surrogacy in India. As writer-in-residence at the University of Cambridge Centre for Family Research, Satinder wrote Half of Me, which explores similar themes to this play. Half of Me accompanies Made in India at select venues on tour.

What was it that compelled you to move into playwriting?

I was researching Meera Syal’s fascinating family history for the BBC series Who Do You Think You Are?, working in Punjab, India. I hadn’t been back to Punjab in years and was there alone for the first time. It was a hugely inspiring, emotional time. I went back briefly to my mother’s village and my father’s village – and cried when I saw my great aunts and those lush golden and green fields unfurl! But I also learnt about untold farmer suicides in Punjab and around India, ecological and economic devastation, due to increased corporate/chemical farming and land grabbing. I had to write about it. I had always wanted to write but never had the confidence – until I got back from that trip. For some reason, and with absolutely no connections to theatre, I felt like playwriting might be a good way to start. I began writing a short play, Zameen, about a Punjabi cotton farmer. I submitted the play to Kali Theatre, where I developed the piece into my first full-length play and production.

How does the stage offer a better platform for this story than, say, television or film?

I do think this story can be explored effectively in any medium, using the full power of the chosen medium – whether it’s documentary, fiction, film or television. But theatre is effective because of the immediate and potentially explosive way it can fuse politics, creativity and emotion through drama, in a communal, distilled and live space. Theatre also demands the issues are kept tight, without the additional visual and narrative space other mediums might give us. By allowing the entwined stories of these three women to take centre stage, we see the essence of what surrogacy and all its emotional transactions entail in the present moment.

What has it been like working with director Katie Posner?

It’s been brilliant working with Katie and a largely female creative team, from the cast of Syreeta Kumar, Gina Isaac and Ulrika Krishnamurti, to the brilliant designer Lydia Denno, lighting designer Prema Mehta and AV designer Shanaz Gulzar. Katie has done an incredible job with the production and a tough script. Where I’m indecisive as a writer, she’s decisive as a director. Trust is so important in creative collaboration and very early on, I learnt to trust Katie with my script.

The theme of motherhood will always be timeless, so how have you reconciled it with the volatile contemporary issues of the story?

As well as motherhood, the theme of surrogacy is also timeless; there are examples in the Bible, in Hindu mythology and Greek mythology. I think there is a real beauty and solidarity in one woman giving birth for another woman, altruistically. The contemporary aspect brings science and money into the process – and suddenly, commercial surrogacy becomes a complex and potentially messy business. So I think it was important to bring these conflicting aspects together through three very human characters, who, with their contrasting but very modern world motives, each want something different from a commercial surrogacy transaction. So in Made in India, the volatile combination of science and economics conflict and play out through the female bodies of these pregnant surrogate workers.

Performances of Made in India have received acclaim from publications and audiences all over the country. What it is about the play that seems to speak to everyone?

Honestly, I have no idea! I think the commercial surrogacy premise of motherhood, reproductive science, fragile relationships between women, the conflicting cultures, emotions and politics involved is so compelling and certainly drew me towards writing the play. I’m very grateful that audiences seem to be embracing a confronting, diverse and very female-centred work that says a little about the “everything for sale” world we live in. I really hope audiences continue seeing the play while it’s on tour, to show that stories like these that are perceived as risky, marginal and irrelevant by the theatre establishment can be thought-provoking, worth telling and will be heard. Especially in a frightening political climate when we all need to speak up and stand up for marginalised global underclasses more than ever.

Your play Half of Me also explores the issues surrounding Assisted Reproductive Technologies. What is it about this subject that interests you?

I think it’s a fascinating subject for so many reasons, primarily because the world is really only just catching up with the rapid advance of this powerful, life-changing reproductive science and its impact on the people involved and society as a whole. We’re only just working out what it means ethically, morally and emotionally – even legally – given that countries such as India, Nepal, Thailand and Cambodia have recently banned commercial surrogacy or the way that donor children are being given increasing legal rights to find their donor parents.

ART is an incredible if sometimes controversial science that has contributed to creating miracle “new families” all over the world. While Made in India is about female infertility and the adults involved in the ART process of surrogacy, Half of Me is an offspring young people’s play about male infertility and the young people born from ART. While researching Made in India, I always wondered if any of those surrogate babies might search for their birth mothers in commercial surrogacy countries such as India, Nepal, Cambodia or Mexico as adults. In fact, a whole ART generation is currently coming of age and we’re only just learning about their unique experiences, growing up in these new modern families, where some youngsters might have up to five parents or half-siblings in double-digits. But in essence, this whole subject is also just about origins, birth, and family – who we are and where we come from – mainstays in my work.

Which writers inspire you and your work?

Oh too many to mention! There are so many dramatists, novelists, poets, filmmakers, artists alike who inspire me and my work; dramatists like Lorca and Arthur Miller to contemporary writers like Arundhati Roy, Jhumpa Lahiri, Tarell Alvin McCraney, filmmakers like Terrence Malick and Joachim Trier, even musicians like Sufjan Stevens, who would definitely feature among them!

You’ve been working with Tamasha’s Artistic Director Fin Kennedy since 2013. How have you collaborated to develop the play over the years?

From the beginning of our 15-plus drafts, I would write a draft and then Fin and I would have the most brilliant, searching, synergistic dialogues about the play that went on for hours. It would take a couple of days to process but was massively helpful in moving onto the next draft. We did this intermittently for about three years – discussion, draft, feedback etc. During my Adopt a Playwright Award year when I began writing the play, we also had three rehearsed readings. We then had another reading and intensive workshop later, so other vital feedback from directors and actors also pushed the play on dramatically. Fin is a hugely talented creative – an excellent Artistic Director, dramaturg and award-winning playwright rolled into one! It helped the process hugely that he is a writer too. He easily understood my creative objectives, obstacles and was always quick to suggest a wealth of dramatic solutions and savage cuts. As a writer, he could help me shape the drama much more effectively than I could alone as he could easily understand the play I was trying to write and help me work out the best possible way of writing it. I’ve just learnt so much from my work and all those creative discussions with him; it’s been an intensive, invaluable process and an incredible experience working with him.

How do you feel India’s ban on commercial surrogacy will affect the practice of surrogacy and potential surrogate mothers in the country?

There are fears the industry will be driven underground through illegal clinics/surrogacy, much like the illegal organ transplant industry in India. There will be a higher degree of exploitation, which could seriously endanger the lives of many desperate and poor women. Before the ban, commercial surrogacy in India was an unregulated multi-billion pound industry. Thousands of surrogate babies were delivered in India for parents all around the world. Since the ban took effect over a year or so ago, the lack of foreign clients is bound to have had a huge financial impact, both on the surrogates not able to find more work and the industry itself. The ban is currently being tabled by Parliament in India but it’s been Cabinet approved and is expected to be made law in the next few months.

When I began writing the play, I was staunchly anti-commercial surrogacy. As I began researching the play more, I realised the issue wasn’t so black and white. Maybe commercial surrogacy with greater regulation is a possible solution. Maybe this issue is about reproductive choice and it’s up to every woman to decide whether she wants to be a paid surrogate or not. It’s such a complicated issue, there are just no easy answers.

While I understand why a village woman in a developing nation would become a paid surrogate, I don’t think it’s right that many women have been so poor and neglected (deprived of adequate education, healthcare, social welfare) that they are compelled to hire out their wombs and deliver babies for money. It’s a systemic problem and perhaps in an ideal world that problem would be urgently addressed, so illegal (or commercial) surrogacy would never be an option.

How has Made in India taken on a different meaning since the ban?

I actually thought I was close to finishing the play about a year and a half ago before the Indian government decided to ban commercial surrogacy. That decision upended a lot of the play. I dropped some favourite scenes and rewrote the play from a different angle. We reshaped the story, which took a few more discussions and drafts, expanding and contracting until the final distilled version of the play. In a way, it turned out to be quite a timely development for the piece because it focused a lot of the issues and heightened the stakes more strongly. I think the play also captures a post-ban world in which society is trying to catch up with the powerful if controversial science of ART and, also, a political climate in which women’s reproductive choice is taking centre-stage once again, albeit through a slightly different economic and scientific lens.

Isabelle Milton

Featured photo: Robert Day

Made in India is at Soho Theatre from 8th until 25th March 2017 before continuing on its tour across the UK, for further information or to book visit here.

Read our review of Made in India here:

Watch the trailer for Made in India here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS