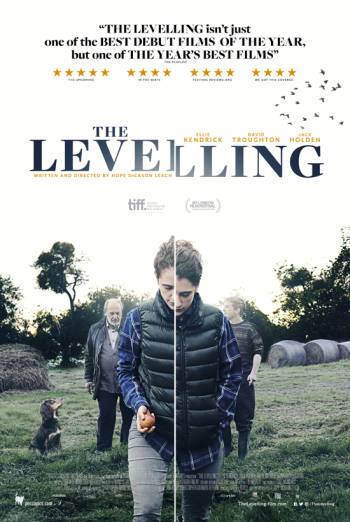

The Levelling: An interview with director Hope Dickson Leach and star Ellie Kendrick

Hope Dickson Leach is a British director whose debut feature, The Levelling, has proved to be a critical hit on the festival circuit. It’s a striking portrait of family and grief, set in rural Somerset, shortly after the floods of 2013-14 decimated many farmers’ livelihoods – and filmed with the sort of rigour and confidence usually attributed to seasoned European directors, such as Bruno Dumont and the Dardenne brothers. We asked Leach and her brilliant star, Ellie Kendrick (best known from Game of Thrones), about the process of making the film, and its exceptional take on some very British issues.

The Levelling premiered in Toronto, which was about nine months ago. How’s the festival tour been?

Hope Dickson Leach: It’s been brilliant. I mean, Toronto was obviously a complete whirlwind, and such a brilliant privilege to premiere the film there – and then London was amazing, bringing it home…

Ellie Kendrick: I loved LFF.

HDL: It was just a dream, and they were so supportive of the film – it was so important for this film to be received well by a British audience. And it’s lovely going to Sweden, and Rotterdam, and dairy farmers suddenly appearing at all these screenings going, you know, “Oh, yes!”.

Where did you get the idea of filming this muddy, elemental portrait of grief in, specifically, Somerset?

HDL: The story was originally the family story – the grief, the family that didn’t connect. What do you need to do to a family like that to make them actually break through and start changing the way they communicate? So I wanted to put them through the ringer, and I had made some shorts about grief – it was something I was interested in – and because it’s a drama, I think context is so important. So I wanted to find somewhere that would really amplify the story; and it was while I was writing it that I saw the Somerset floods.

I went down and met with some of the farmers, and just started listening to their stories. It just seemed like such an extraordinary and specific experience to have gone through that I thought it was actually more universal. I always think the more specific you can be, the more universal [the story] is, and it just appealed to me on so many different levels. You know! The dredging, all the kind of visual stuff that I think cinema is so good at – the metaphorical, cinematic things that work well for something that’s ultimately quite intimate.

Was it a tough shoot? I’ve read reports of mischievous cows…

HDL: (Laughs) I mean, it’s tough in the sense that you’re working long days, and you’re outside, and there’s mud… But actually, no, I think I had a lovely shoot. We knew it was going to be muddy, we knew it was going to be emotionally intense, we knew it was going to be, you know, hard and tight and fast. But what was a top priority for me and the producers and such was that this felt like a safe, secure place; because I was just very keen that the performers, the actors, who were going to be opening up emotionally, had a safe atmosphere.

And I worked really hard to cast the crew – when I was meeting [assistant directors] I needed someone I knew I could trust, who would have the same approach, the same kind of calm, that would reflect the way I’d like to work. And I think we did have a crew and a cast who all felt very invested, so it felt like a real collaboration. Because however hard it gets, you’re all making the same movie – it’s still rewarding.

(To Ellie) And for you, was it a hard shoot?

EK: I mean, it was obviously pretty emotionally intense, because your script asks its performers to go to some pretty dark places. So it was hard work. But I love working hard when I enjoy the project. And Hope was great at the helm – she made us feel very welcome and invested in the project, and you’ve got to have that if you’re working on an independent film. Because that’s all you’ve got – the community. You’re definitely not getting paid well! You’re definitely not getting a lot of time, the food isn’t going to be the best… Actually, we did quite well there.

HDL: Our food was actually quite good.

EK: Yeah, it was probably the best independent film food I’ve ever had!

HDL: Turning that around nicely.

EK: But yeah, it’s got to be so much about the community and the atmosphere, and actually, [Hope] made that possible for all of us. We all sort of fell in love with each other.

HDL: We did, we really did. But yeah, obviously, the cows were difficult…

EK: There were some moments of actual terror.

Even though it’s a little European in its formal sensibilities, this struck me as a very British film – and I mean that in a good way! Specifically, it really seems to engage with the idea of the “stiff upper lip”, where people are reluctant to confront emotional problems.

EK: Denial, silence, yeah.

Was this something you set out to dismantle?

HDL: Absolutely. And I think that’s why it’s interesting that [Ellie’s] character is someone who’s had this very British, army, middle-class upbringing – you know, boarding school and all that – and [to look at] the effects of this, with the family now falling apart, and everyone dying. Where does it take you? And that was something that I believe quite strongly as a human being – I think there’s something to be said for casting aside these shackles of Britishness and trying to move beyond that.

EK: Agreed!

The film is also so interesting in terms of class. Because the conflict between Aubrey and Clover isn’t as simple as working class vs middle class – it exists at a kind of borderline between upper-lower and lower-middle. Why do you think this is such a recurring problem in British cinema?

HDL: I think class is something that’s really hard to talk about, to make work about, and I think that social-realist cinema we see usually depicts the working-class. And so this is something that I would say is middle-class. But I think in the countryside, class is a whole different thing, and taking [the story] out of the urban environment, we were certainly able to look at it in a different, more concentrated way.

And I guess that, even though this was made before it all happened, this does feel like a very post-Brexit film – in terms of the generational divide, realising a family member isn’t quite who you thought they were… Are you comfortable with this reading of the film?

HDL: Yeah, absolutely. I think this is one of the reasons why we’ve got to where we are, politically, today: older people thinking that young people don’t understand, young people thinking older people don’t understand – this lack of communication and knowledge about each other’s life experiences. And it’s Brexit, but it’s lots of things in the world.

EK: And it’s also doubly resonant because Brexit’s going to be hitting farmers particularly hard…

But they voted for Brexit?

EK: Yeah, exactly. So I think it’s telling about this film, that it’s becoming more resonant with time.

HDL: And it’s a community that’s still… (She sighs) I mean, when we were making it I was thinking, “This is such a hard life, such a hard way to make a living!”. And it’s inescapable, because it’s a family thing, you inherit it, you can’t sell a farm for what it’s worth because very few people want to buy farms. So it’s this kind of emotional, financial burden. And now… It’s a harder and harder lifestyle, and I have more and more respect for people who are doing it – and I think we need to engage with them more.

Thank you so much for talking to us – I’m already looking forward to your next film!

HDL: Me too! (Laughs)

Sam Gray

The Levelling is released in selected cinemas on 12th May 2017. Read our review here.

Watch the trailer for The Levelling here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS