Venice Biennale 2017: The top ten pavilions

The 2017 edition of the Venice Biennale opened last week, offering a glimpse of the most cutting-edge contemporary art being produced around the globe. A staple of the art world calendar, at its core the event consists of specially produced artwork from each of the 57 participating countries, presented in a unique pavilion. This is usually either a specially designed permanent space in one of the Biennale’s official locations, or one of several requisitioned buildings around the city. The Biennale has grown to include a host of collateral events and exhibitions, meaning that, for a few months every two years, the historic city of Venice becomes the top international destination to see contemporary art.

This is our guide to ten of the most interesting, experimental and beautiful pavilions at the 57th Venice Biennale.

Austria: Licht-Pavilion – Erwin Wurm

Austria’s Licht-Pavilion draws the gaze immediately across the Giardini due to an upended truck installed outside the entrance. After climbing to the top, visitors are invited to stand and gaze out at the view over the Venetian lagoon. Similarly, throughout the pavilion artist Erwin Wurm offers a selection of unremarkable objects, made special by small, hand-written instructions about how the viewer should interact with them. Each work humbly asks for only a minute of your time – to put your arm through a hole or sit quietly with your legs drawn up – but the effect is to make you question the active role of the viewer and the moment when meaningless object becomes meaningful artwork.

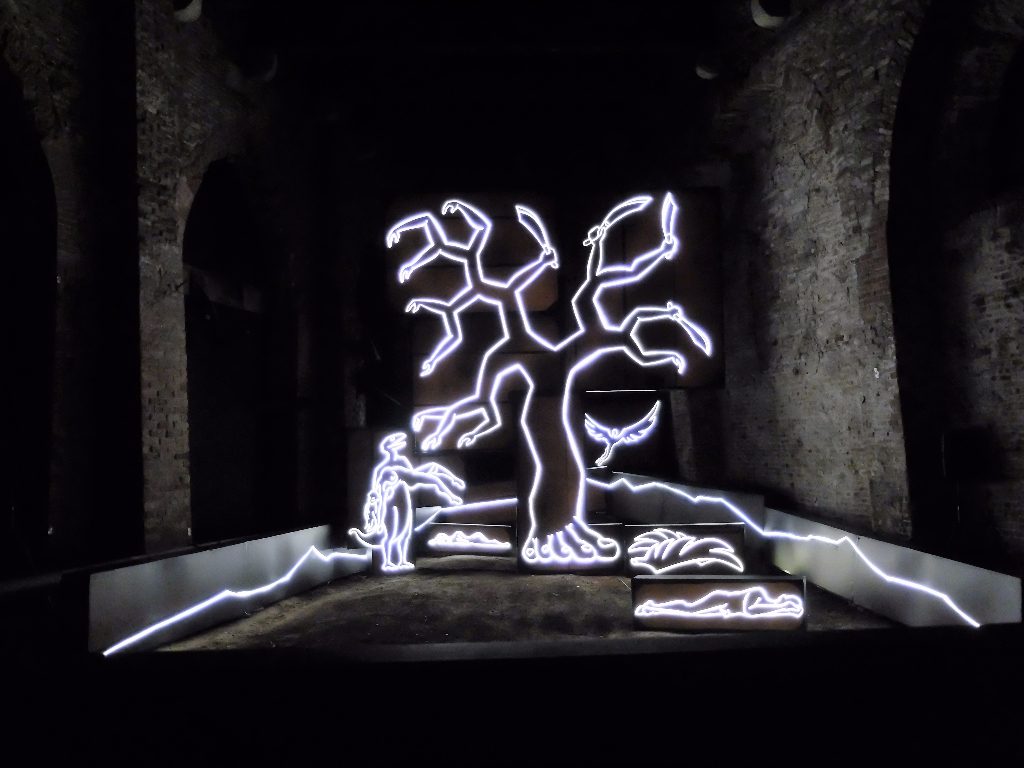

Greece: Laboratory of Dilemmas – George Drivas

George Drivas’s Laboratory of Dilemmas combines video with immersive installation in a work based on Aeschylus’s play Suppliant Women. It’s a poignant nod to Greece’s ancient cultural heritage at a time when, as a nation, Greece is struggling with major political and socio-economic issues. But this reference to Aeschylus shows that these problems are far from new: it’s the age-old dilemma of whether to help foreigners in need at the risk of creating more problems at home. The video couches it in terms of a historical scientific experiment where scientists accidentally discovered a new type of cell. They debated whether to allow the new cells to mingle with the ones being studied, which might either improve the culture or destroy it completely. Presented in piecemeal fashion through speakers, texts and video arranged in a labyrinth, the viewer is uncertain how they should feel about the points of view presented.

Japan: Turned Upside Down, It’s a Forest – Takahiro Iwasaki

The best way to approach the Japanese pavilion is from below. Wait in the queue to climb the stairs, and put your head into the small hole to find yourself the centre of attention. It’s embarrassing to suddenly find yourself part of an artwork without your consent, your eyes and nose peeping out of a hole in the floor while other people stand around laughing at you. But it’s also a highly effective way of making you question your own instincts, as your first impulse is to rush round to the other entrance and stand watching other people popping up where you have just been, and to laugh at their startled expressions in turn. The work is by Takahiro Iwasaki, an artist born and raised in Hiroshima, a city whose history has deeply affected his art. The installation includes tiny detailed pieces, only visible at eye level when visitors pop up through the floor, addressing the micro and macro, and echoing the atomic bomb which, through the interaction of tiny atoms, destroyed a whole city.

Iceland: Out of Controll in Venice – Egill Sæbjörnsson

You can find the Icelandic pavilion over on the island of Giudecca, tucked down a back street. Go inside and you’ll be offered a coffee, to be stirred with a tiny crafted “troll spoon”. Inside, there are tables and chairs on three levels, with viewing holes looking out onto the opposite wall, where a huge animated troll is being projected. According to the artist, this work wasn’t made by him at all, but by two trolls who took over production from him after working for several months in his studio. Their interests include perfume-making, fashion, drinking espresso and eating tourists. By allowing these imaginary characters full rein, Sæbjörnsson has eschewed conventional social constructs and favoured the free flow of creativity. A bit mad, but wonderfully so.

Georgia: Living Dog Among Dead Lions – Vajiko Chachkhiani

Artist Vajiko Chachkhiani is interested in the lives of average people who are invisible in the eyes of history but who still contribute to it. His installation consists of a typical Georgian house, found abandoned in a rural mining town, purchased and meticulously recreated in Venice. There’s something unsettling about it, though, because it’s raining inside the house, while viewers outside remain dry. Sparse belongings are soaked, the wallpaper is peeling and an unpleasant smell of mildew emanates from it. Initially, the interior was dirty and the water washed it clean, but because it falls relentlessly the rain will eventually cause the objects inside to decompose; over the course of the exhibition, mould and moss will grow inside while the outside remains unchanged. Chachkhiani compares this to how a person is changed inside by traumatic events, although they appear the same externally. It’s tragic and fascinating in equal measure.

New Zealand: Emissaries – Lisa Reihana

This work by Lisa Reihana is a fantastic example of how contemporary technology can be used effectively in art. One huge wall of the pavilion is taken over by a projected panoramic image, where a number of narratives involving real actors are played out against an animated background. The viewer’s eye is drawn to one vignette and then another, distracted but also drawn in by the way the panorama travels along the wall, accompanied by a moving soundscape. The narratives are taken from interactions of colonialist conquerors and native peoples of the Pacific Ocean, from New Zealand, Australia, Hawai’i and Tahiti. The installation interrogates the gaze of imperialism, pointing to the multifaceted nature of every story as well as the interconnectedness of history.

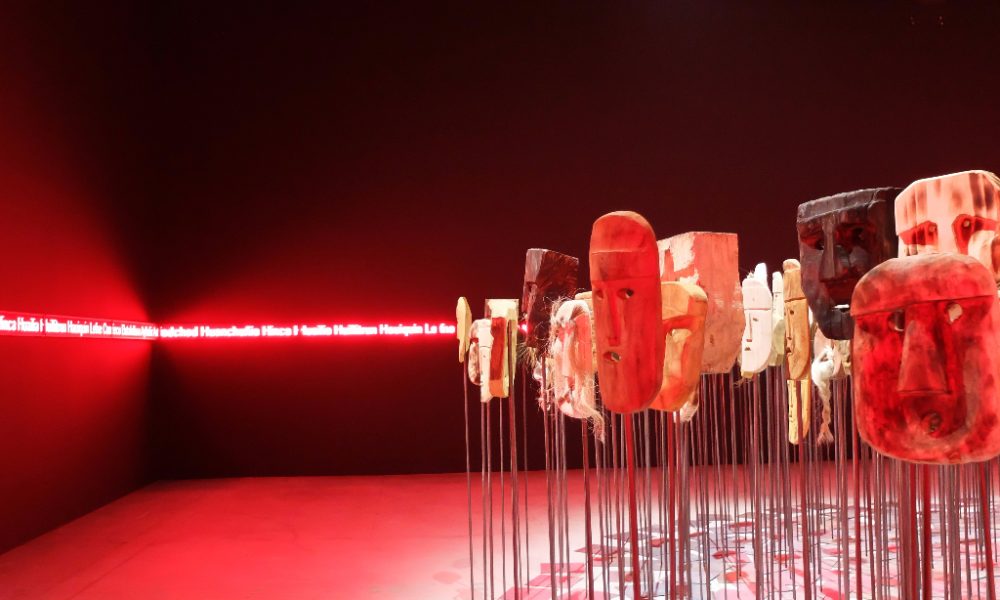

Latvia: What Can Go Wrong – Miķelis Fišers

The title of the Latvian pavilion – What Can Go Wrong – can be interpreted in a number of ways: as a reckless or carefree question or a statement of risk. Miķelis Fišers is drawn towards bodies of knowledge that are seen as unsubstantiated or without status; that which is esoteric or conspiratorial. Consequently, his visual language is one of monsters, aliens and futuristic technology. These things populate a series of cartoonish carvings, featuring titles such as “Aliens Force Musicians to Defecate in the Orchestra Pit at the Metropolitan Opera, NY” and “Modified Squids Loot the Potash Plant”. Unafraid to use humour, the installation points to the bizarre things human beings find to fear in the face of genuinely unsettling changes in our environment and government.

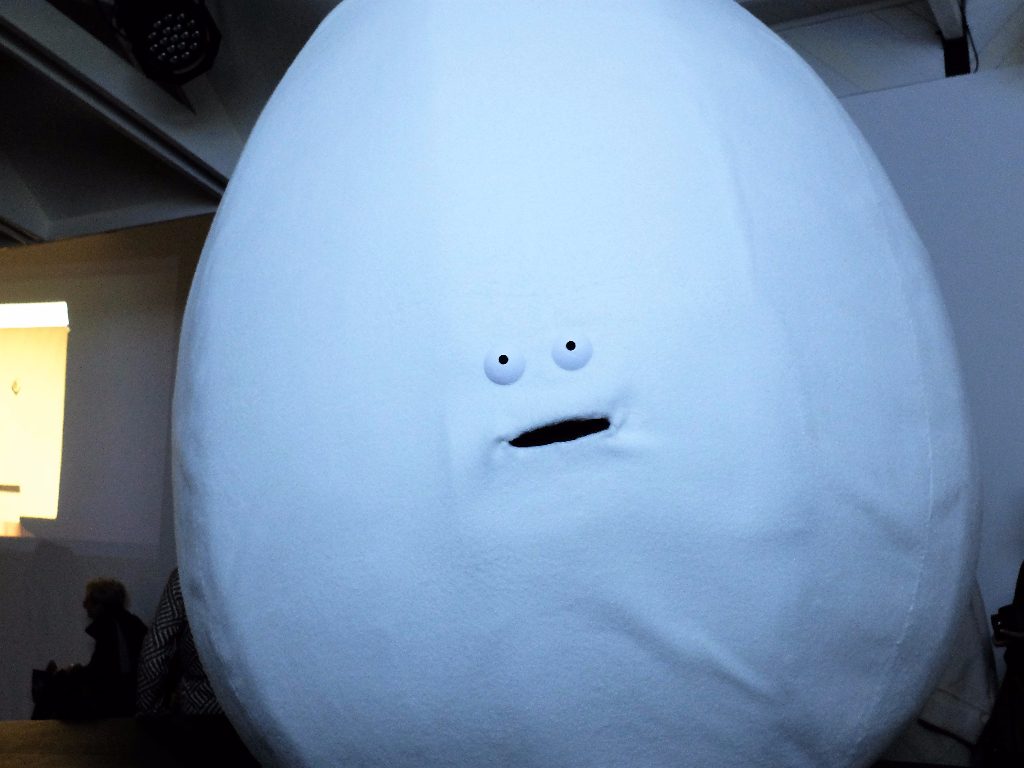

Finland: The Aalto Natives – Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen

The Finnish pavilion is another place where humour is used to great effect. Artists Mellors and Nissinen have worked together to produce a video piece complemented by a giant animatronic talking egg, using absurdity and laughter to confront profound issues of morality, power and communication. An examination of Finnish culture is made through the eyes of Geb and Atum, two God-like figures who supposedly created the country millions of years ago. The interrogation is nominally directed towards Finland, but the use of universally recognised childhood entertainment features such as Muppet-like puppets suggests the wider applicability of their questions about nationalism and tolerance.

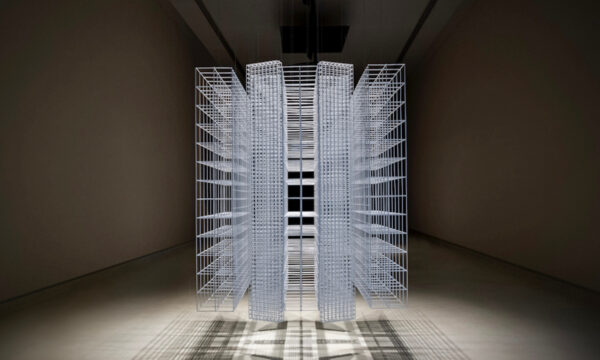

Britain: Folly – Phyllida Barlow

Phyllida Barlow’s installation for the British Pavilion is intended to explore every facet of the historic architectural space. It starts outside the building and makes its way inside, sometimes dissecting rooms or crossing spatial boundaries. The title – Folly – refers both to the purely decorative buildings that were a key part of Romantic English landscape design and to the state of foolishness that the word implies. Barlow’s installation is fun, with its bright colours and lollipop-like structures, but it also feels somehow sinister: these foreboding details can be found in a huge crushed cardboard tube and in the towering pieces that look far too flimsy for their height. These strange recycled creations invite the viewer to consider the concept of sculpture and to form their own unique response to objecthood.

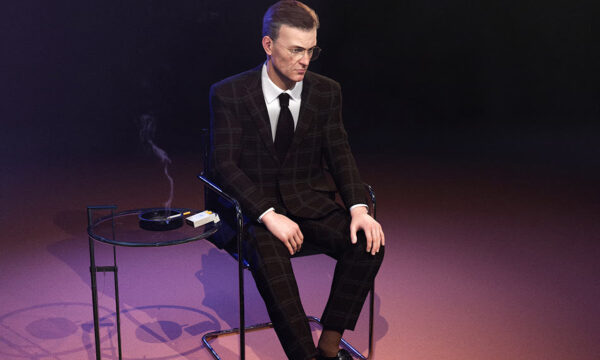

Hyperpavilion

Last but not least, the Hyperpavilion is located on the opposite side of the Arsenale, accessible only by boat. It’s not a national pavilion like the others on this list, but it’s worth mentioning as one of the largest spaces in the Biennale in 2017. Picking up on some of the biggest intellectual trends of the last year, the Hyperpavilion examines the merging of life offline and online, networked culture and hyperconnectivity. Work by 11 artists is on show, including video pieces, immersive digital experiences, installation and performance. Theo Massoulier offers a series of strange hybrid objects, all part-organic, part-technological, that look like futuristic sea creatures, attractive and repellent in equal measure. Also particularly effective are an installation and performance from Aram Bartholl consisting of a mirrored tank situated on a large sheet of brand logos and a pair of security guards who ask visitors to hand over their phones so they can check their Facebook profiles. The dim lighting adds to the sense of paranoia that the visitor is being viewed as well as doing the viewing, drawing attention to the growing global culture of surveillance.

Anna Souter

Photos: Anna Souter

The Venice Biennale 2017 is open from 13th May until 26th November 2017, for further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS