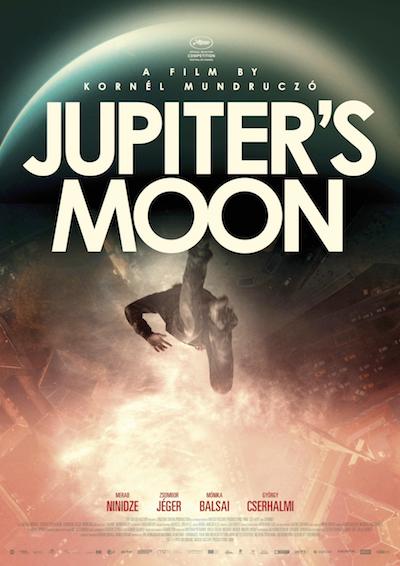

Jupiter Holdja (Jupiter’s Moon)

This is a movie with grand ambitions that aren’t ultimately reached. Hungarian filmmaker Kornél Mundruczó has produced something confrontational but the persistent symbolism and heavy-handed metaphors don’t quite click. It is a picture for Cannes: grand, sometimes beguiling and momentarily overwhelming. But there is a lack of control, and it’s hard to be sure whether this lack concerns its moral clarity or its broader sense of purpose.

Jupiter’s Moon starts claustrophobically and encouragingly. Migrants are hunched up together in a truck, chickens are squawking – then the heaving mass are on boats, being split up, with awful echoes of the past paradoxically suggesting a dystopian future. The boats are shot at; men, women and children go under. There is panic and survival. There is silence and death. The intensity of this opening, the close-ups and the content of these scenes resemble the excruciating, unbearable Son of Saul, from Mundruczó’s fellow Hungarian director László Nemes. The focus becomes much slacker from here, though. Among the Syrian refugees is Aryaan (Zsombor Jéger), a wide-eyed boy who apparently can take three gunshot wounds without much trouble, but pants a lot after a few long-distance sprints. After an unprovoked attack, our man begins to defy the natural laws we take for granted. The odious policeman, László (György Cserhalmi), discharger of the bullets, will stalk him throughout. Aryaan has help, however, in the form of the objectionable Dr Stern (Merab Ninidze), whose motivations are at first financial and self-serving. After a botched operation, heavy litigation hangs over the doctor, and the pair must help each other as government forces close in.

Some of the gravity-defying scenes are breathtaking, and the twirling Aryaan high above the sprawling city is an image difficult to eradicate. The film builds tension like a thriller in quite conventional ways: in chases, near misses and ominous pursuits. The talk of religion, God, the nature of existence and the assertion of value are sometimes achieved with a bit of a twinkle – Aryaan’s father was a carpenter, after all. But largely Mundruczó takes it seriously, and so he should while addressing the refugee crisis, tyranny in Hungary, corruption and the modern loss of morality. Such seriousness requires control and focus, however, and like its protagonist the film constantly grasps for the celestial outer reaches, while the angels choose to stay firmly within the Earth’s atmosphere.

Joseph Owen

Jupiter’s Moon does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

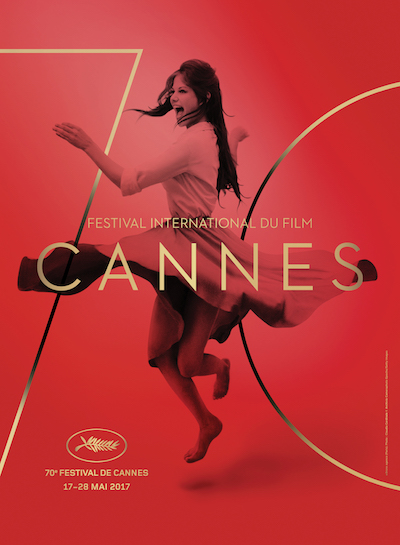

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS