120 Battements Par Minute (120 Beats Per Minute): Press conference with Robin Campillo, Adèle Haenel, Nahuel Pérez Biscayart and co-stars

Robin Campillo’s latest entry to Cannes draws on his intimate experiences in the ACT UP AIDs advocacy movement in France in the early 90s. He suggested that this was a film he had wanted to make for a long time.

“I was a militant myself for several years. Recently, I had the feeling I was hesitating too much. I was a bit afraid to tackle this topic. I thought it was high time I dealt with it… I’ve lived things which appear in the film. I had to dress a friend of mine who had died. These are simple moments, where you don’t break down and cry. It’s hard to get through that kind of a moment. [As a filmmaker] I focus more on the cold side of things. There are strange impressions and icy moments in the film.”

One notable element of the feature is the widespread excellence of the large ensemble cast. Campillo stated that managing the volume wasn’t easy: “It’s tough enough with one actor and, here, there are about 20. It’s a question of controlling things in fiction, to help people make the film themselves. I spent a long time on the casting. It took me quite a while to strike a happy balance with the cast.”

Campillo wished his actors to feel the intimate scenes, to show vulnerability: “I wanted very naive things in the film, particularly with Sean [played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart], and in some of the very tender scenes. This is a love story of someone who is sick, someone who is not well at all.”

Adèle Haenel, who plays group organiser Sophie, thought that “the film is very touching because of these clumsy moments. That’s what happens in real life.” She also alluded to the importance of each character: “I love the irreplaceable nature of the people. The film would have been totally different without one of the group.”

Theatre actor Antoine Reinartz outlined Campillo’s demands for his role as group chairman Thibault. “He had me shave my hair, shave my beard, lose weight and tone my muscles. But things were very democratic during the shoot. There were all sorts of different people and it is wonderful forum for debate.”

The characters Sean and Nathan emerge as the central couple of the movie, and Campillo lets their relationship develop organically out of the group. “Fiction is linked to one’s innermost life. It is something between the collective experience and a very intimate experience. What was a group story became something individual. I wanted to depict this group as a brain that gets things done. The debate scenes shaped the relationships between the characters and the fiction emerges out from the whole group.”

On the set-piece debate scenes that appear throughout the film, Campillo explained the process. The ACT UP movement was small, but had more than a hundred attendees each week. “We shot the scenes with three cameras and we rehearsed for about three days. I rewrote a lot of the script in that time. Things weren’t really improvised in the course of shooting… Things were very theatrical indeed [in the amphitheatre]. We were pretending to be angry and then the anger became real because we realised what the people we were attacking [the pharmaceutical companies] were really like.”

The precise politics of 120 Beats Per Minute are sometimes ambiguous, but the urgency of the HIV plight is presented in the starkest terms. Campillo noted of the period that “the epidemic had gained in magnitude and people were afraid to speak out. The results were tragic. In the film, people feel free to speak. Society [at the time] seemed totally indifferent…”

The director added that “things work well when there is a real struggle. This happened with abortion, and it happened with AIDs as well. But it’s hard to mobilise people in France at the moment… People came together because of the disease because of the epidemic. They came to represent quite a strong political movement. I hope the film will help mobilise people today.

“ACT UP was a burning necessity and a way of empowering people, enabling them to come to grips with the situation. Swapping information about the disease was very harsh. People became very violent, particularly those who had become [HIV] positive or were very ill. But there were a lot of joyful times because it was a form of freedom and release, although it was a very deadly time.”

Of depicting the time period, Campillo explained that some liberties should be taken: “Films cannot be rooted in an era, it must be able to transcend this. I wanted to hear a certain music when people spoke. I wanted people to speak like homosexuals and to appear naturally militant.”

The title derives from the house music the filmmaker listened to while volunteering for the group in his youth. “The beat was pretty fast. I wanted to pay tribute to this music that was typical of the times. I love the music in the film and I wanted to really underscore that there was an anxiety too.”

Joseph Owen

Photo: Neilson Barnard / Getty Images

Read our review of 120 Battements Par Minute (120 Beats Per Minute) here.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

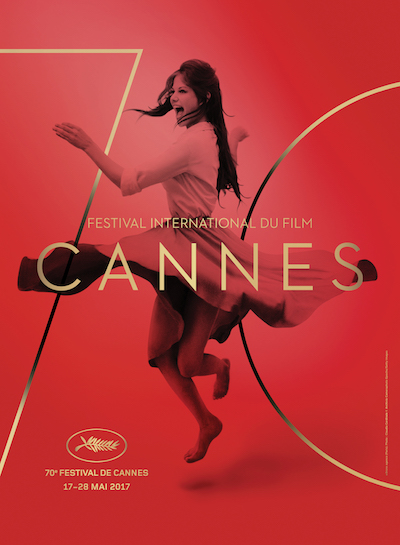

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS