Jupiter Holdja (Jupiter’s Moon): An interview with director Kornél Mundruczó

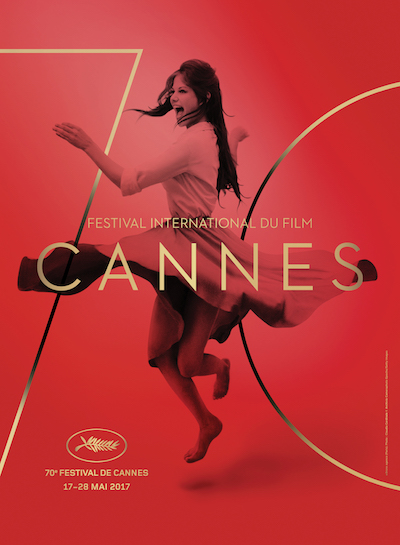

Jupiter’s Moon is a genre-splicing, expansive evaluation of religion, Hungary and the refugee crisis. The film has been shown in competition at this year’s Cannes and received a mixed response from critics. It is the second in a purported trilogy on perspective and belief, after 2014’s White God. We interviewed Kornél Mundruczó a few days after the press screening of Jupiter’s Moon in the Palais. We spoke with him about his newest film, contemporary politics and his faith.

Hello Kornél. Did you have any trouble from the Hungarian government for making a film about refugees?

Not really, it is surprising. I lived there when this crisis happened so it is about my own city and the shame I felt. I’m still European; I’m still a human being; I’m still moral. Hungary supported some of the movie, and Germany the other half.

Do you think film can help change the way people think about these problems?

I hope so, yes. If you understand from the movie that you can sacrifice yourself for a refugee, this means there is a hope that this crisis is evoking new ways of thinking.

Did you mean to give the film a religious overtone in order to draw in the people who might be most opposed to refugees?

Yes, definitely. In Europe you have thousands of years of Christianity, but sometimes I feel that we completely forget that. At the beginning, the character of the doctor [Stern] is a complete nonbeliever. He’s a bastard actually. He’s drinking and cynical and loveless. He’s changing his emotional drive in the film. Aryaan does not have any real character, as he is more like an angel, more like a confession room. Stern is always talking to Aryaan and through that ride he is changing.

It’s a conversion.

Yes, luckily.

Dr Stern asks, “What have I become?” very early in the movie. Is he asking that question for the whole of Hungary?

Exactly, but this is a European movie. I’m Hungarian, my roots are Hungarian, I live in Budapest and I was there when this crisis happened. But still it’s a European problem in the here and now. It’s very provocative to make a film like this. There are ideological, relative answers from the left, from liberals, from the right and from the far right. I hope art and dialogue can help. My film is another perspective on this problem.

Do you show the way in which we use refugees for our own purposes?

Yes, they work for us. Dr Stern at the beginning is using Aryaan for his own needs. It’s something very strange because it’s about money and success. The flying was the first idea in my mind. I always close my eyes and see the figure that is levitating and flying and I have to react.

It’s a very bold idea to have a living angel. How nervous were you about going down this road?

I know the danger, I know the risk and I just jump into it. It stays with me. I’m not counting on what you want. I do what I want to do. It’s risky; it’s crazy. And there are audiences waiting for unique and special stuff. Can I make a movie about miracles? Can I make it that these miracles are rational and close to us? And question you as a viewer, do I believe it or not? Is this craziness or could it happen? I do it in a way that is very up front, not in a mysterious way. He’s flying, he’s there and you watch it.

Is the film about Christian Europe, and what does Viktor Orbán [the Hungarian Prime Minister] think?

I’m not sure. What is Christian Europe? There can be right wing people who are very religious and all they want to do is build big jails. I don’t know what Orbán thinks. My question is whether Pope Francis likes it or not.

You talk about taking risks and you have one of the refugees commit a suicide bombing. Did you feel the response to that might not be the way in which you intended?

We know it’s a very provocative move. We wanted to blow up the city and have a huge emergency. After the Bataclan attacks I was in Marseille, and it was difficult to travel up to Paris and then onto Brussels because of the emergency. It’s a reaction to create a new reaction, a rupture. We have an angel who is a refugee. I didn’t want to hide from showing something that wasn’t politically correct. Somebody makes a bomb for God, somebody makes a jail for God, so it’s always about questioning our belief. Dr Stern finds Aryaan and starts making money off of him. I think that is much more provocative than a suicide bomber. So many happenings like that, it is part of our life. The question is the level of representation. If art cannot represent, than who can represent? Newspapers?

Did you consider not showing the flying, as this is a film about belief? Did you want to test our belief?

It was a huge discussion beforehand because, if it’s in front of you, you’re much more suspicious. If you just see reactions, it’s very intellectual. We were pushing much more to the front and making the miracle like a miracle. We do lots of real stuff like wires and cranes, and we shoot all on location. There is not much CGI in it. We used a spinning room.

Does this multi-genre approach have its advantages?

I really like mixing genres. If I make a social drama it’s not very close to me. For me it’s about stylising and having a poetic level. This is grounded and dark but also like an action thriller. It’s fantasy and it’s a “what-if?” movie.

Dr Stern is a Jewish name. Was this deliberate?

Yes, Dr Stern is a Jewish name, a very intellectual name. Aryaan is a very holy name, but also there are Nazi connotations. I think contradictions make the truth. There is no clear truth and we use those names as a contradiction. Everyone in Hungary knows Dr Stein, like John Smith in English.

The film has a documentary feel.

Yes, everything was built. When the refugee crisis happened we had lots of footage and we filmed our version of reality, as the camps were no longer there. Now we have a fence and Hungary is the most right wing country in Europe because we are not dealing with the refugees anymore.

Can you explain the meaning of the title?

The idea behind it was very simple. I wanted this to be seen as a European film. This is what Jupiter’s Moon represents for me.

In light of contemporary Hungarian politics, how do you feel about the attempted closure of the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest?

It’s really a shame like many things are. It’s like the fences. To live there, it is not as black and white as in the foreign papers, but it is tough. It is pure populism.

Do you think the Hungarian population has a tendency towards authoritarianism or are they being manipulated by the press and the government, or is it a mixture of both factors?

It’s really loaded with fear, fear of the unknown. Now if you name that fear – refugees, intellectuals, Brussels, George Soros – people just follow it. It’s a combination, though; it’s not just pure manipulation. After the economic crisis, it started to get worse.

They scapegoat other people for their economic concerns?

Exactly.

What are your thoughts about the future of the European Union?

Why are we creating this culture? Where is this abstract thinking coming from? When something unexpected happens, you have to face it. On the one hand it’s a problem, on the other it’s a mirror to us. I am quite cynical about the EU. If it’s just an economic issue between the big countries than I don’t really know why Hungary is in it. But I can’t really be sceptical, because if we are not part of the EU then what, where are we? It’s a complex and contradictory question. There is no real truth. I don’t know what’s going on. It’s a huge responsibility for society now, like we are in a war somehow. We need to find a way out and build again. It’s a moral war.

Did you always imagine the film would end with ascension?

I don’t know. Someone leaves the movie, and five years later I want this person to remember that image. So many movies you forget even if it’s a moving story. But what you cannot forget is pure cinema; it should stay with you forever. I wanted this film to be like a Hieronymus Bosch image. It’s chaos and then when you get closer you see all the detail in miniature. This movie is as much falling as flying. We will remember this tension that we have today. This time is different from Stalinism. You can create a cinematic language that can serve that idea. The camera is restless; it doesn’t stop running. There is no rest. This movie is difficult to watch sometimes. I hope that it stays with you.

Jospeh Owen

Photo: Mátyás Erdély

Read our review of Jupiter Holdja (Jupiter’s Moon) here.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Watch the trailer for Jupiter Holdja (Jupiter’s Moon) here:

https://youtu.be/2q_ufeEMGM8

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS