120 Battements par Minute (120 Beats per Minute): An interview with director Robin Campillo

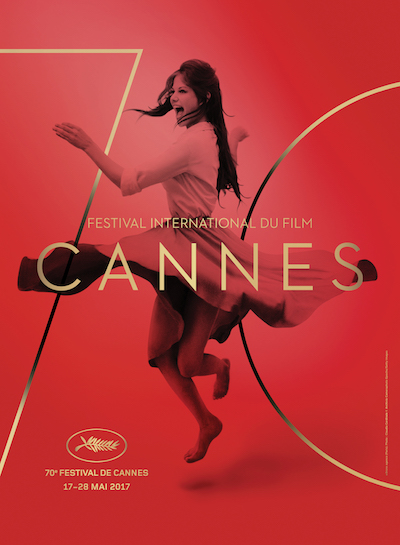

120 Beats per Minute is the latest feature from French director Robin Campillo. It has been shown in competition at this year’s Cannes and has received a positive response from critics. Some have even tipped it for the Palme d’Or. The film follows the HIV advocacy movement ACT UP, interrogating the politics, social lives and relationships of its members. We interviewed Robin Campillo a few days after the press screening of 120 Beats per Minute in the Palais. We spoke with him about his newest picture, his previous works and his experiences as a member of the militant group over 20 years ago.

Hello Robin. This film is based on your own experiences. Can you speak a little about that?

I wrote the script based on my memories of the early 90s. I didn’t go through documents first. I tried to create a fiction from my vivid memories of these meetings and I wanted to recreate the music and electricity between all these people. It was only after that I went through documents to be sure. What I like in these memories is the reality and pure imagination at the same time. It was like a film by Marcel Proust about activists. From the beginning I wanted it to be a self-portrait of a group.

Why are these memories so vivid?

Because it was an important moment in my life and it marked me a lot. Even in ACT UP I was thinking about a film on AIDs activism and I couldn’t find it. I thought it needs to be about ACT UP and that would be a good angle. It’s a moment when people have been the victim of an epidemic for ten years and were trained to take back power, and it’s more positive and lively even if it’s sad. But there was some kind of energy and I wanted to talk about it.

The use of debate and forums are central to the movie. Do you think ACT UP would work in a different environment, one perhaps dominated by a purity of belief rather than a desire to get things done?

Forum is an interesting word because it is used on the internet, which isn’t a real place. People can be more radical in forums, but they are not really radical in reality. In ACT UP we were confronting the laboratories, the institutions and the governments, but first of all we were confronting each other. We had to go and debate; we were ill and had a lot of problems. The body was very important. We were dreaming of political action. There was a kind of poetry that exists because we had great ideas that we couldn’t do – the river with blood, for example. The forum is like a brain but with real bodies inside, and it was always possible for someone to talk in a strong debate and say, “I’m ill, let’s do something”. It was always this movement between the collective and the personal. We were so lonely in the 80s during the beginning of the epidemic because we realised as gay men that we were invisible. There were other AIDs groups in France who were helping people in France but they were the good gays and we were the bad fags. We had a different role in this story and sometimes the groups were very connected, with groups saying we were stupid but quite right about some things. The confrontation was productive, and fun, too. It was a sense of theatre as well. Some people are nostalgic about ACT UP – it’s a little bit fake to say that we were always angry, and sometimes we acted angry even if people were ill. We were playing but it became real because of the sincerity.

You mix the intimate and the personal and the political and the social. Was the intention to change the focus as the film went on?

I have this obsession with the idea that you have a big house at the beginning, and you don’t know what will be the fiction and who will be the protagonist. As a spectator, how do you become a real character? How is the fiction created in this group? There is a love between Nathan and Sean [the two protagonists who emerge]. I had a friend who fell in love with a guy who was HIV positive because most of us were, and six months after the guy gets sick so you have to live in a real love story. Maybe six months ago you would dump him, but you have to be a companion at this moment. My friend said, “Maybe I’m in love with this guy because he’s going to die and it’s romantic, but maybe it’s fake”. And he was afraid of that, but you don’t know when it’s fake because it’s complicated. Sean says to Nathan in the hospital, “I’m so sorry it has to be you”. This is important.

How do you draw the line between fiction and reality?

It’s difficult. For example, there was the case of this woman who had a child who was a haemophiliac and that’s how he became HIV positive. She said, “We need to take action because there’s a lot of blood in my bath and I can’t take showers”. It was surreal, that’s why it’s so vivid. The woman in the film says, “AIDs is you, AIDs is me, AIDs is us,” and that was real! In France, we were in the midst of an epidemic, there were strong feelings and we were in a time of war. But there was humour and it was fun.

Is there a character in the film which is you?

There is a part in the film that is part of my story. Thibault, the ACT UP chairman, has my attitude. I love him. He’s very active and at the same time he looks like a child sometimes. There are some autobiographical things about me in there.

How did you discover the actor who plays Sean, Nahuel Pérez Biscayart?

He’s an Argentinian actor and he’s going to be big here in France. I love the character because he’s a trickster. It’s like he’s in a silent movie. Then you have Nathan who is quiet and doesn’t talk at the same pace. I love the contrast of all those characters. The good thing with Sean was that it was hard to find someone who gets angry in the debate, and you can feel that his body is failing behind all that. It was becoming personal. You can’t explain that to an actor. I’m fed up with actors who are like children and expect you to be the father. Let people get into the room and invade my film. If the actor is not the character, it’s better that the character becomes the actor. As the director it’s not exactly what you want, it is better. You don’t confront people to make them what you are; you meet them in the middle to make them what we all are.

Your film is being tipped for the Palme d’Or. Do you read reviews?

No, I’m a nice guy but I’m a little bit paranoid. Even if it’s good, it’s not enough. I’m too anxious.

When everyone meets at the end it’s very moving. Did the changing of the clothes really happen?

I changed the clothes. I did it with a mother that I didn’t know so well. She was talking to him, and it’s weird to say but I thought it was funny. I wanted to say, “I think he’s dead”. It’s anaesthesia. He was really thin and had a lot of strange things in his body. I remembered when my friends came through the door and said they could do it for me. I was not moved in the moment, I just thought I had to do it and it will be better. The woman from the hospital was there. She was asking everyone, “Do you want a coffee?”. It was a little comical.

Why make a story of your youth now?

My first film Les Revenants is the idea of dead people being good for nothing. Maybe that was why it was a disappointing film for some. It was a liberation for me as a director, to get out of myself and security zone. And this was a process that got me to this film.

Was this film always in the back of your mind?

Yes, I found the desire to make other films in ACT UP. It may be naïve but people made me stronger there; I felt legitimate. It was my school. We were doing crazy things and we were not afraid to be ridiculous. There’s a slogan from the 1968 revolution in France: “We will die not being ridiculous”. I am now trying to make films with stupid things in them. This film is closure.

Would you say your films are obsessed with conversation?

Yes, but I will try and be more silent in my next films. It started with The Class with Laurent Cantet because we were interested in people talking and negotiating. They negotiate a lot about money and sex; even the sex scenes in this film are negotiations. When you are talking about prevention you have to talk. What’s a condom? What’s your HIV status? It’s very interesting to see how people talk.

Was it important to have some intense love scenes in the film?

I like to show the things beside. In most sex scenes people are already naked and they know the Kama Sutra. I love the fact that you have to get your clothes off, and one has an orgasm and the other does not and now we’re going to discuss it. Sometimes cinema doesn’t want to show what is beside. When someone dies you don’t go to the funeral directly because the corpse is there. The magic of the cinema takes us directly to the funeral. But the real magic is in everyday life; it is almost surreal and more important than supposed reality.

Does a political culture exist like the one ACT UP prospered in?

I think in France groups are fed up with racists. There are Arabian and Black groups. I know France isn’t the most politically correct place to be and there is a lot of Islamophobia. What is strange is that I don’t agree with all groups necessarily. People are saying things about them, though, the same things they were saying about us in the 90s. France is not very good with minorities. That was the main problem with the AIDs epidemic. We’re such a universalistic country, you see.

Joseph Owen

Photo: Neilson Barnard / Getty Images

Read our review of 120 Battements par Minute (120 Beats per Minute) here.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS