Hikari (Radiance): An interview with Naomi Kawase

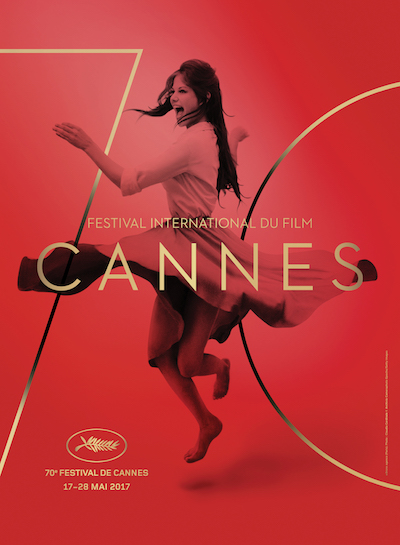

Radiance is the latest feature from Japanese director Naomi Kawase. It has been shown in competition at this year’s Cannes and has received a mixed response from critics. The film contends with the audio description industry, a unique premise in cinema, and analyses ideas of blindness, communication and aesthetic understanding. We interviewed Naomi Kawase a few days after the press screening of Radiance in the Palais. We spoke about her newest film, the power of audio description and the way her family experiences influenced her work.

Hello Naomi. Why did you choose audio description as the topic for this film?

On the way back from Cannes a few years ago I was amazed by the detail and care put into the words used by audio descriptors. I felt that these guys must really love film and if I use an audio descriptor as a protagonist I can show my own love of cinema.

Will the film be shown anywhere with audio description?

It’s not open in Japan yet but when it is there will be screenings for visually impaired people.

What exactly is cinema if it’s not moving images?

I don’t think being able to see is the only thing cinema can offer. Other than that, it’s a media that lets you feel. The world portrayed on screen is something that’s seen, but what you hear and how you feel comes from a 2D screen to the 3D world we really live in. Cinema reminds us of this fact because the visually impaired live in this big world that is cinema. They feel cinema as if they are lying in the cinema itself, so by having audio help there’s the possibly that they understand the film even more than those who do not. I was talking to the producers of audio guides and their love for cinema was very close to mine. These encounters instigated the making of this film.

What is the importance of the Rolleiflex camera for the character?

The Rolleiflex is very good for portraiture. It’s like your bowing, so when shooting you’re liberated of any nervousness because as the photographer you are looking down, not at them. That results in very natural expressions. The character Mr Nakamori considered portraiture one of his best types of work. Now he can’t see and he wants to connect with people but he is suffering and it is painful because he cannot take photos anymore.

Your film deals with the idea of too much and too little. Can you explain this idea with regard to your work?

It’s exactly that. If you explain everything, it’s too much for the audience. But if you take too much away the audience won’t understand. So how to keep that balance? How to elevate the audience’s imagination? That’s always my challenge.

Is your picture a gentle counterbalance to the rest of the competition at Cannes?

Cannes always has a balance, and that’s why it’s garnered so much respect. A few years ago I had the privilege of being on the competition jury headed by Steven Spielberg. I had the great opportunity to discuss cinema with lots of other people. I don’t want to be presumptuous but Spielberg and I shared a very similar love of cinema. He makes big entertainment and I do independent films. If it touches you in a certain way then that’s the best type of cinema. I think my film in competition speaks to the wonderful sense of balance at Cannes.

What are the most special moments for you when making a film?

Well, we got lucky with the sunset. We didn’t even have to call in NASA! But most important is what you throw away as well as what you keep. In the editing process lots of beautiful moments are lost, but this ultimately generates a better picture.

Some things that inhibit people can be also productive. Do you think that blindness can develop someone’s intellectual and aesthetic sensibilities?

I can’t generalise but many blind people who I met were able to see before. They were not born blind so they have the memory of seeing. It’s a convergence of their memory and what they’re hearing about the world. For me, their words were very strong, encouraging and truly beautiful. It’s true they lose something with their sight, but because of that they are able to gain it is something very beautiful as well.

How did the music of the film come about?

Ibrahim Maalouf, who composed the score, is very much into improvisation. Whatever he sees, feels and hears he turns into music, and that’s very similar to the way I make films. He saw bits of my screenplay and he started sending pieces of music which I then chose.

What if you were ever to lose something crucial to your job?

The idea of losing vision is something that I could relate to very much. But the power to overcome with newfound strength and a sense of beauty is a journey we could relate to.

Is this film related to your family history?

The girl in the film [Misaki] is wearing my grandmother’s clothes. There is no father, which is my private reality too. My family background was projected into the picture.

How important was nature to your film?

Where we shot always had a river and a mountain. It’s not just about contemporary times; it’s about the people who have lived there in the past. And by capturing that I hope it would carry that feeling to the younger generation.

Is this film inspired by your own story?

There is a part of that. Not just me, but for every artist whatever you’ve lost you may want to recreate. That becomes part of the process. The suffering you’ve experienced becomes something you can truly digest and give light to.

Joseph Owen

Photo: Anne-Christine Poujoulat / Getty Images

Read our review of Hikari (Radiance) here.

Read more of our reviews and interviews from the festival here.

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS