L’Amant Double (The Double Lover): An interview with François Ozon

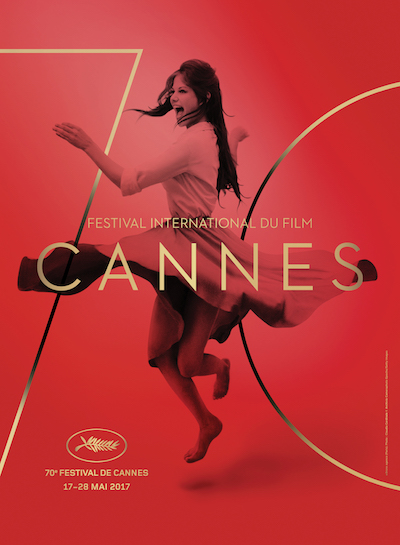

Director François Ozon’s latest feature, L’Amant Double, tells the story of Chloe, who begins a relationship with her therapist, and looks at the identity issues of twins. The film is based on a short story by Joyce Carol Oates and ran in competition at this year’s Cannes.

Are you a big fan of Joyce Carol Oates?

I’ve long admired Joyce Carol Oates for her precise writing style, keen psychological observations, complex characters and smart storylines. And the fact that she’s a graphomaniac has always appealed to me. When I learned she wrote mysteries under the pseudonym Rosamond Smith, I took an immediate interest in these minor novels, knowing her limitless imagination would provide great fodder for film. That’s when I came across Lives of the Twins. I retained the premise of the book: a woman discovers that her psychiatrist, now her lover, has a brother who is also a therapist. Joyce Carol Oates tells the story in a far more realistic way, whereas I delved further into the mental aspects of the story, set the action in France and added the medical revelation at the end. Still, the film explores the American author’s pet subjects: neuroses, sex and the dark side of split personalities.

Was it the subject of twins that inspired you to make this film?

I wanted to treat the subject of twins as something fascinating, monstrous and artistic. I got the idea of having Chloe work in a museum. Chloe is contaminated by the artwork she’s guarding. At the beginning of the film, the pieces in the museum are fairly aesthetically pleasing, but as the film progresses they become increasingly organic and monstrous, reflecting Chloe’s inner turmoil. I naturally thought of Dead Ringers. I suspect Joyce Carol Oates wrote her book after seeing Cronenberg’s film, which is also very organic and preoccupied with gynaecology. However, in his case, the story is told from the point of view of the twins, whereas JC Oates focuses on the young woman caught between two brothers. It was important for me to place Chloe at the centre of the story, to show her stomach, swelling and hurting her, and illustrate her confusion between early pregnancy and a parasitic fetus.

How did you want to present the process of psychoanalysis?

For a long time now I’ve wanted to try to capture the experience of a psychoanalytical session on film. Initially, Chloe sits across from her shrink, monologuing about her dreams, her feelings and emotions, her family… The audience is plunged into her private life and might get nervous – will this be going on for an hour and a half? I didn’t want to confine myself to the classic analytical setup represented by a neutral, static setting with predefined codes. I sought to capture something more fluid. I wanted the audience to follow Chloe’s therapy the same way a psychiatrist might listen to his patients, in a floating way. The visual effects and changing viewpoints in these first sessions almost play against the dialogue. If you listen carefully or see the film a second time, you realise everything is said in these first ten minutes. But you don’t necessarily hear it.

Does the balance of fantasy and reality allow these characters to lead double lives?

The Louis character can be seen as an avatar allowing Chloe to live out the desires and fantasies she forbids herself from experiencing with Paul, as though her love for Paul were preventing her from satisfying a more intense and uninhibited sexuality. My films are often about our need for the imaginary in order to cope with reality. In any love relationship, even a happy one, there is an element of frustration and a need for a mental space where fantasies can express themselves. Our partner can never satisfy all of our desires. We often need something more or different, something on the side.

So L’Amant Double is a mental thriller?

The intense subjectivity of the first ten minutes bleeds into the rest of the film. The idea was to follow Chloe in a linear way, creating narrative tension by playing with elements of suspense while staying anchored in a fluctuating reality complete with moments of mental or fantasmatic slippage. This allowed me to deviate from a purely realistic register and flirt with the character’s imaginary world. I liked the idea that the outside dangers and threats Chloe perceives reveal her inner turmoil.

How did you approach directing this film?

After a restrained, classical film like Frantz, diving into Chloe’s imaginary world gave me room to make bolder stylistic choices. L’Amant Double tells an essentially mental story, and my idea was to direct it architecturally, playing with symmetry, reflections and geometry. All the sets were conceived to create the impression that something is being built, that a brain is developing a thought. I shot my last few films in 35mm but for L’Amant Double, I returned to digital and cinemascope and aimed for a sharper, more contemporary image, surgical at times, but always aesthetically pleasing.

You worked with Marine Vacth before on Young & Beautiful. Why did you cast her for this project?

When I dreamt up the project four years ago it didn’t occur to me to cast Marine as she was too young for the role. But by the time I returned to L’Amant Double after Frantz, Marine had matured, had a baby, become a woman. And we were both keen to work together again. In a sense, Young & Beautiful was a documentary portrait of an up-and-coming young actress. In it, Marine embodies a taciturn, opaque, mysterious teenager onto whom the audience projects their own interpretations. In this film, Marine has done the work of an accomplished actress and truly created a character. The secret is within her, she’s seeking the key to unlock it, and we’re right there with her on her quest. We get inside her head, her fantasies, her stomach.

Did you feel the same about Jérémie Renier, who you have also worked with before?

This is the third time I’ve worked with Jérémie, after Criminel Lovers and Potiche. In my mind he was still the teenager I met in 1998, so I wasn’t convinced going into the screen tests. I assumed he wouldn’t have the necessary maturity for the roles, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover he’d acquired a strength, a virility. And when he tried out a few scenes with Marine there was a real erotic chemistry between them. The starting point for playing Paul and Louis was simple and binary: good guy, bad guy. But as Jérémie infused complexity into the characters, it quickly became apparent that the trickier of the two to tackle was actually Paul. He’s the more mysterious of the two, the one who’s hiding the most. We can project more onto him, he triggers our imagination. We worked on the costumes, hairstyles, physical differences, the way they carry themselves, the way they speak. In the beginning we imagined a deeper, more imposing voice for Louis, then realised that if they have the same voice the situation feels even more disturbing. Like Chloe, there comes a point where we no longer know if we’re with Paul or with Louis.

Can you tell us a bit more about these two characters and how they are portrayed in the film?

I wanted Paul to come across as a good psychotherapist whose exchanges with Chloe ring true. Louis, on the other hand, transgresses all the rules and framework of psychoanalysis. He makes outrageous claims and interpretations. In their first session, he gives the impression he knows Chloe, leading the audience to wonder if he might actually be Paul. It’s as though Louis were saying out loud everything that went unsaid with Paul, and saying it brutally, with no taboos or superego. Everything relating to the brothers is conceived in mirror images, especially the decor. Paul’s consulting room is comfortable and inviting, with leather furniture, plush carpeting and warm colours. Louis’s consulting room is glacial, with marble accents, cold colours and fake flowers. As for the mirrors themselves, Paul’s are horizontal and Louis’s are vertical.

There is also an interesting focus on these characters’ mothers…

The three women in Chloe’s life can all be seen as mother figures. Myriam Boyer, who plays the neighbour, is the intrusive, slightly grotesque, devouring mother, a bit of a witch with her taxidermy cat. I’ve always loved Myriam Boyer’s voice. In no time at all she establishes her character, the only one in the film who brings a little humour and lightness to an otherwise disturbing presence. Jacqueline Bisset is the real mother, the absent mother Chloe mentions at the beginning of the film during her session with Paul. In her fantasy world this maternal figure becomes Mrs Schenker, a nurse-cum-prison warden who cares for her incapacitated daughter at home. Jacqueline Bisset was an obvious choice, with her Anglo-Saxon charm, feline beauty and resemblance to Marine in her facial features, skin tone, freckles and piercing eyes. Dominique Reymond is the clinical mother, the scientist who gives Chloe information about her condition kindly, but without emotional attachment. I love the combination of coolness and empathy Dominique brings to the role.

What can you tell us about the final reveal?

It was while doing research on twins that I discovered the existence of parasitic twins. That was a eureka moment in my adaptation process, because it provided a path back to a reality even more fantastical and monstrous than what we’d seen up to that point. This final resolution plunges us into the abyss of what nature is capable of doing to our bodies. There’s a serenity at the end of the film. Her condition has been diagnosed and treated, things seem to be falling back into place. But all is not resolved. Chloe still feels the emptiness inside. I don’t see this ending as either positive or negative. It is brutal and unrelenting, like sexuality, the subconscious and desire.

The editorial unit

Read our review of L’Amant Double here.

Read more of our reviews from the festival here.

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS