Redoutable: An interview with Louis Garrel

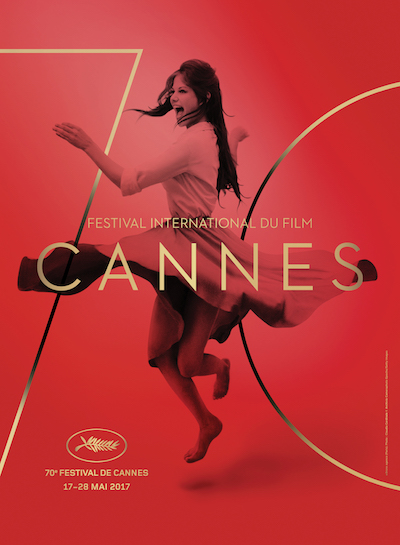

Louis Garrel stars as Jean-Luc Godard in Redoubtable, a biographical drama about the relationship between the director and the actress and novelist Anne Wiazemsky in the 1960s, which screened in competition at Cannes this year..

Your admiration for Jean-Luc Godard’s cinema is well known. Bearing that in mind, how did you welcome Michel Hazanavicius’s proposition to play him on screen?

Taking this part was far from a foregone conclusion. For any actor, the role of Godard would be very intimidating. Godard has played and continues to play a central role in my work.

Think of a Christian, for whom the figure of Christ is a profound inspiration… How could he play Christ on screen without having the painful feeling he is descending into blasphemy? It’s a little like that for me. My first reaction was: as his admirer, I can’t play Godard.

Then Michel and I talked a lot while he was writing. He explained that this wasn’t a film about Godard. He talked to me about Un an après, Anne Wiazemsky’s book, whose point of view is the central theme. Redoubtable is less a biopic than the story of a filmmaker caught at a specific turning point of his life that converges with a historical turning point. The period in question is short but dense. It begins with the filming of La Chinoise and goes up until the beginnings of the Dziga Vertov Group. And for all the rest, it’s before and after May 68.

It is also a love story. So I started to see it more clearly. Later when I read the script I was captivated from the first page. It was like a sophisticated collage. And I was attracted by the subject, it was enthralling. I learned many things about the Dziga Vertov Group and the complicity between Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin… But what surprised me most was the way it was presented. Godard moves away from film, cuts himself from his network of contacts, throws himself into activism… And at the same time he’s racing in that direction, his relationship with Anne goes to pieces. All this is in the book, but Michel’s screenplay reminded me of an Ettore Scola comedy! Even though the narrative content is dramatic, the situations are all shown in an amazing comic light. Politics in particular never ceases to produce burlesque comedy.

Did you find this the right approach?

Yes. Less in keeping with what 1968 could have been than with what you hear from those who were there… Even if these experiences are composed of a combination of joy and drama, even tragedy, it’s often the absurd, even the comical, that is also highlighted in the story. A result of hindsight, I’d say… While he didn’t live the events of 1968, Michel talks about them in the same way as those who knew the barricades, meaning that he emphasises the joyous and vital side of the revolution.

This is the third time I’ve acted in a film about May 1968. Bernardo Bertolucci’s approach in The Dreamers (2003) is phantasmagorical. My father’s Regular Lovers (2005) is poetic. I didn’t want to repeat myself. But Michel’s point of view is different again: he uses the codes of dramatic farce or Italian-style comedy; his point of view is both critical and tender… After all, Godard himself, in replying to a question about May 68 and cinema, said it was a subject for Jerry Lewis.

Aren’t comedy and politics contradictory?

Probably. But you can’t separate Godard from his taste for paradox and provocation, for deconstruction and, yes, for the comic. Provocation is an integral part of his way of being and working. Godard is incapable of getting involved with anything – a television set, at an assembly, even a novel – without deconstructing and reconstructing. I heard Gorin say that he has only ever made first films. Dissatisfaction and perpetual motion have made him the inventor of modernity, the Picasso of cinema.

The film is above all a love story – how was working with Stacy Martin?

I knew Stacy from Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac, and was impressed with her performance. Even more so after I met her, since she is very different from her character in the film. I don’t know how she coped during the shooting of our film, but in each scene she managed to impose an authoritative tenderness that, in the face of all opposition, makes her love the character I played. In the end, she embodies a very intelligent woman, lover and friend. And with an immensely graceful beauty.

What do you think of this movement that in 1968 made Godard leave the bright lights of cinema for the shadows of activism?

In 1968 Godard decides to leave the place where he is absolute master to go into politics. I feel that for Michel, this shift is dangerous: he doesn’t believe that artistic practice can coexist with such militant activism. I agree in part: this shift perhaps appeared to lead him to a dead end. But with hindsight, one can also say that it’s from that place that Godard reinvented himself. And I can only admire his journey. I think it’s very powerful… All the more so in Godard’s case because it leads him to explore the limits of cinema. It is characteristic of his approach since the beginning: to redefine cinema through its limits, without respite. He continues today with films like Goodbye to Language (2014).

Did you look at documents to prepare for the part? Films? TV interviews with Godard?

All the time; I always have, even when I’m not playing him. In interviews he can be inhibiting. The way he appreciates films at unexpected moments. I think his apparent severity is a sign of a deep and constant need for the other. He needs to break up. But not rupture. He needs to determine himself in relation to the other: to deconstruct, cut and edit all relationships…he tells us that when he was a boy scout his nickname was bickering sparrow! He is someone who needs arguments, discussions, confrontation…the presence of the other, but a true other, meaning someone who resists him. I believe all these aspects are in the film.

You’ve always had a reputation as one of his best impersonators – and there are many. Was this your starting point for portraying him?

Yes and no. Michel and I wondered which Godard we wanted to show. Because there are many. We mostly know his media image. The risk was to reproduce this image during intimate moments, which would be misplaced. We also know Godard the actor, in his own films: I’m thinking of First Name: Carmen (1983) where he plays himself as a madman of sorts, or Keep Your Right Up (1987) in which he’s very funny. These elements had to be there. But they weren’t the only ones.

How did you prepare, physically?

Did I need a wig? I thought any sort of fakeness had to be avoided…but I didn’t really know what had to be done. Michel convinced me in the end by showing me a sketch of how he saw Godard, the glasses, the tuft of hair, etc… And from that everything became clear. And the idea of the comic book convinced me. A comic book tone. We tried to find a modulation between the image in the media and a more intimate image, to play on different registers… For me this modulation is essential in approaching the character.

I often told Michel that I absolutely wanted to avoid hurting those who love Godard. And he used to reply that he didn’t want to frighten those who hate him. The film is a balance between these two desires and two fears. That’s Michel’s inclusive side. He conceives of a film that can be seen by a very wide audience. He loves the idea of addressing the whole world. I tend to see things differently. I’m very happy of the meeting of our two different approaches.

The film could give the impression that it was partly improvised…

That’s the effect we wanted to achieve. But we managed it by doing the reverse. The car scene illustrates this perfectly. They are coming back from Cannes. There are six of them crammed in the car going back to Paris. That’s already quite funny in itself. It becomes hilarious when you know the context. Godard had driven south to block the festival. Although a supporter of the struggle, his friend Michel Cournot would have still liked his film Les Gauloises Bleues to be screened. From this, a terrible argument explodes. Michel filmed it as sequence shot, in a way that we were all in the frame constantly. And we are even more crammed especially as everyone is involved: Renoir, Hawks, the whole story of Cinema that Godard says he is done with… The scene seems improvised while in fact it was planned down to the last millimetre. It took us two days to be able to give Michel what he wanted. A large part of the material was unusable because of our hysterical laughter. There were long silences during which it was really difficult to refrain from laughing, it was so funny. There are directors who are really inside the action and who love the work of the actors. Michel is one of them.

What is the vision of Godard that finally emerges from the film?

The image of a man who wanted, at a decisive political moment, to turn cinema into an art that makes you think, at the risk of getting on the wrong side of people who loved him for other reasons. Michel’s view of the era isn’t nostalgic, nor is he crushed by the figure of Godard. It is a curious and tender look. And that’s how I’d like the audience to see the film.

The editorial unit

Read our review of Redoutable here.

Read more of our reviews from the festival here.

For further information about Cannes Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS