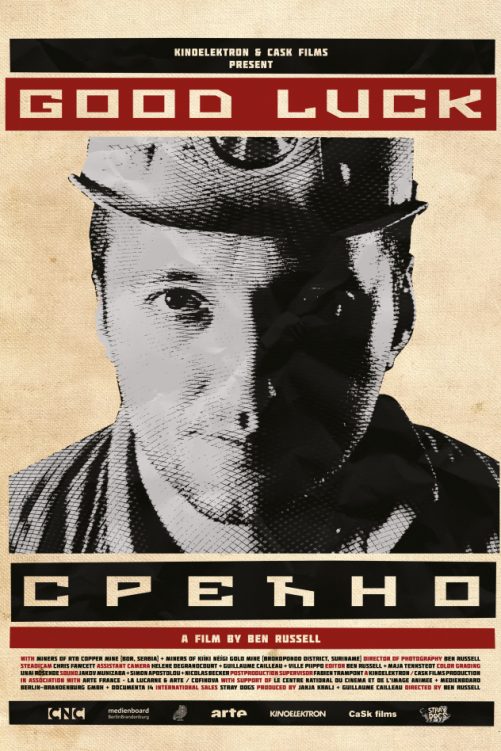

Good Luck

Filmmaker Ben Russell has produced something extraordinary with this slow, meditative and engrossing nonfiction study of two mining communities in Serbia and Suriname. Composed of long, long, artful shots – beautifully captured on Super 16mm – Good Luck descends deep into the Bor copper mine for the first section, before travelling to a gold facility in the tropical Americas for the second. From both halves a picture develops of a collective working class experience, one forged in circumstances of avaricious production, civil conflict and institutional neglect.

The state-owned Serbian mine, unsurprisingly, is dark and claustrophobic. Unlike its fictional thematic cousin Winter Brothers (also playing in Locarno), this film shows the industrial underground as psychologically oppressive rather than maniacally violent. Almost all of the men are over 40 and likely to have experienced the Yugoslav conflict. The impression is that they have now given up on themselves. Through an interpreter Russell queries, “What do you fear?”. Their obvious response is “nothing”. Some joke about their wives. There’s no revelatory statement. What we derive instead is their collective reticence and communal embarrassment when being asked how they feel. Such epistemological enquiry is irrelevant to their lives. They just work: for a higher salary, perhaps, or for their family’s contentment. Meanwhile in Suriname, a country offering white heat and financial precariousness, the workers reminisce on their lack of opportunities. The war, they quickly agree, is the reason they’re in the illegal gold mine. There’s no trace of pity, only acceptance. As these countries have failed to banish their warmongers and political extremists from political life, is it surprising that their populations are disenfranchised? In both instances, the education these men were not afforded is the precise thing they wish for their children. And Russell’s thoughtful, removed ethnographic approach shows how a socially constructed relationship of thought develops among them. Because of their monosyllabic responses, the men must be understood through extended images of their work.

Some viewers will have their patience tested – many shots are uncompromising in length. But this seems part of the point: to show the arduous monotony of labour. Russell interrupts these takes with portraits of workers alone in front of a camera, captured with a slightly incongruous silent-film lens filter. Probably instituted to mitigate the verbal omissions, it isn’t entirely satisfying. Such minor points don’t detract from the unique splendour of the film. In these two worlds the aesthetic, economic, cultural and political distinctions are evident: between darkness and light, North and South, white and black, legal and unlawful. Russell shows that it’s the toil, the sense of resignation and the twisted process of time – along with the accompanied disorientation time provokes – that unites these men.

Joseph Owen

Good Luck does not have a UK release date yet.

For further information about Locarno Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS