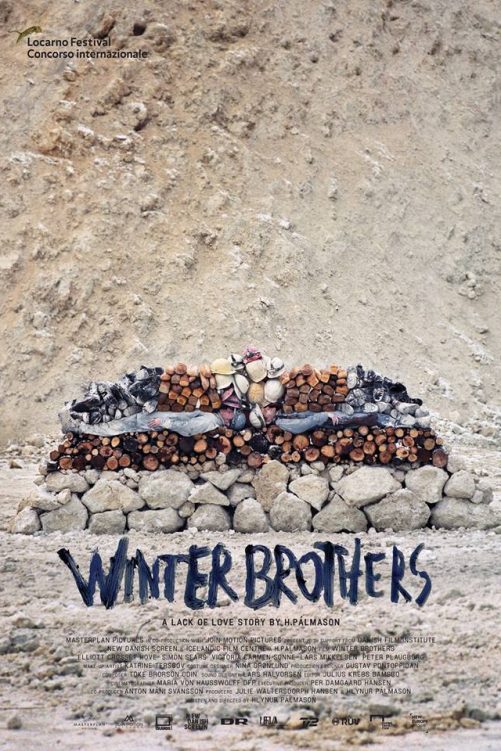

Vinterbrødre (Winter Brothers)

This is a brutish, elemental feature debut from Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason. Set in a limestone mine somewhere in rural Denmark, the film follows two brothers as they negotiate the severity of an abrasively cold winter and vicious male antagonisms. The clear aesthetic is black and white, the darkness of the pits set against the blinding brightness of the snowscape, the pure whiteness that merges seamlessly into air. Violence brews here. Because in these primal conditions, what else would? What else is there?

Emil (Elliott Crosset Hove) is the inscrutable younger brother to Johan (Simon Sears). Both work in a stunningly bleak and harsh terrain where men’s faces are spoiled with a strange mixture of snow, muck, sweat and rubble. Emil preoccupies and enriches himself by selling dodgy, “toxic” concoctions that the others drink readily. For the workers, this venture only slightly offsets his peculiarity – it will ultimately confirm their suspicions and damn him in turn. The brutality of the pit – the ruptures of violence that bubble beneath the surface – are viscerally depicted. Yet it is on land where Emil faces most immediate danger. Emil’s boss (Lars Mikkelsen) sadistically toys with him over a report on one worker’s illness. It was apparently the result of alcohol poisoning – the hearing doesn’t end well. Emil finds intimate and erotic solace in the sole woman, Anna (Victoria Carmen Sonne). Her encounter with Johan, which is barely perceived but hardly ambiguous, results in an astonishing naked wrestle between the brothers, the likes of which have been missed since Oliver Reed and Alan Bates rolled around in Women in Love. It’s certainly a more graphic interpretation. Emil otherwise obsesses with a rifle, which is brought home in the form of disturbing army-training tapes that crackle on TV. Not only do these unsettling videos interrupt his dreams, they shape them, an imprint of his internal strife and contradictory understandings of modernity.

This is not quite the state of nature – no matter how close the director would like to bring it to us – but we do glimpse the primitive, in the groups of men, the heavy machinery, the churn of industry, the endless landscape. The discordant score effectively apes the milieu. Pálmason has constructed a beautiful, consciously dramatic film, although it’s a shame that Anna’s character is merely a receptacle for male lust and anxiety. The picture’s unbridled masculinity is evident throughout, but it is otherwise difficult not to applaud this exhilarating work.

Joseph Owen

Vinterbrødre (Winter Brothers) does not yet have a UK release date.

Read more reviews and interviews from our London Film Festival 2017 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the official BFI website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS