What makes The Room “so bad it’s good”?

With the release of The Disaster Artist in cinemas this week, a spotlight has been fixed directly on Tommy Wiseau’s 2003 “disasterpiece”, The Room. Known by many cinephiles and cultists as the worst film ever made, the movie has gained an incredible cult following and is continuously screened in cinemas across the world. For those unfamiliar with The Room, the idea of a picture as mind-blowingly poor as this being celebrated so much may be perplexing. Why should this get a pass whilst other bad movies like Suicide Squad are scalded by critics? The answer is simple: The Room is “so bad it’s good”, but what do these words actually mean?

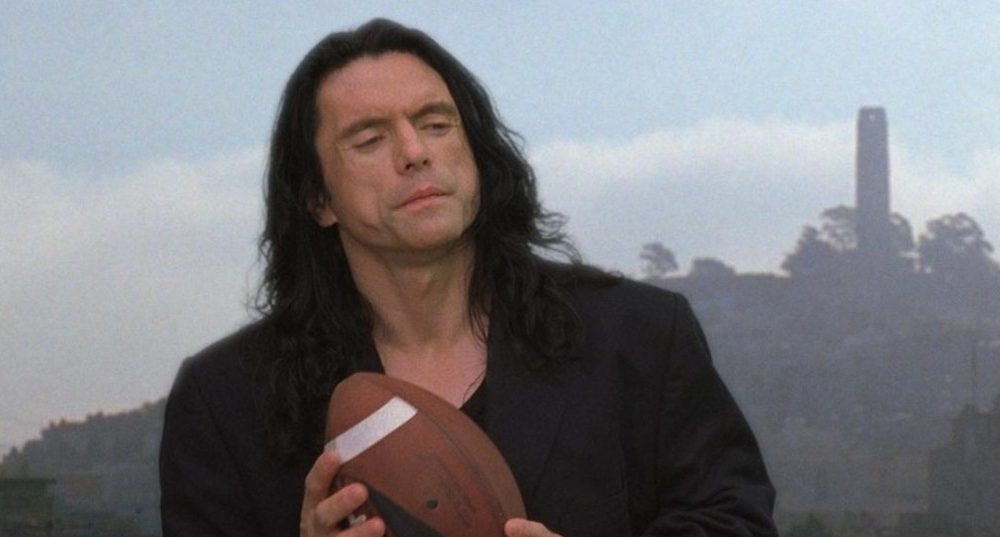

Dave Franco and James Franco in The Disaster Artist

What’s crucial about “so bad they’re good” films like The Room, Plan 9 from Outer Space or Manos: The Hands of Fate is that they demonstrate a bewildering incompetency in filmmaking. As movie scholar J Hoberman writes: “The objectively bad film attempts to reproduce the institutional modes of representation, but its failure to do so deforms the simplest formulae and clichés so absolutely that you hardly recognise them.” Take The Room’s infamous flower shop scene, for example. What should be a simple exchange between Johnny (Wiseau) and the shop attendant is botched so much with horrendous ADR and editing that it becomes hypnotic in how terrible it is. For Hoberman, spectacularly bad features are “anti-masterpieces” that “break the rules” of filmmaking and, more importantly, “project[s] a stupidity that’s fully as awesome as genius”.

A key part of determining if a flick is “so bad it’s good” therefore lies in its ability to adhere to conventional standards of filmmaking. In their analysis of The Room, MacDowell and Zborowski argue that the movie fails to adhere to conventional standards of narrative, dialogue and continuity. Of course, for audiences to recognise these failures, they must themselves be familiar with the conventions these features fail to meet, but these conventions are not only technical. In her analysis of Troll 2, for example, Philips highlights one sequence where a building that’s clearly a church is referred to as a house. Here, audiences can recognise a “rule” has been broken and can laugh at the blunder.

Though we chuckle at these failures, it’s preferable if these gaffes are unintentional. Sharknado is a bad film, but it’s intended to be so; when we laugh at Sharknado, we’re aware it was made to be schlocky. The beauty of The Room, however, is that its badness is fully unintentional. As much as Wiseau may claim his work is a black comedy, audiences are laughing at it rather than at any jokes the director intentionally included.

As much as fans mock The Room, there is a genuine adoration felt towards it. Cult film scholar David Ray Carter described the concept of cinemasochism as being the act of finding bad movies “charming” where the cinemasochist seeks to “stomach the worst that cinema has to offer as a badge of honour”. Moreover, cinemasochists will riff on a film to highlight moments that deserve to be ridiculed whilst celebrating them for added entertainment. Throwing spoons at The Room is a strange act of love fitting for such a strange picture.

The Room is a disaster, but it’s the best kind of disaster imaginable. Displaying such incompetency, Wiseau’s feature is a huge success precisely because it’s a massive failure. More than just a bad film, it has become a symbol of Wiseau’s desire to make his movie, which makes The Disaster Artist a love letter to filmmaking in much the same way as Tim Burton’s Ed Wood. In short, The Room is great, but for all the wrong reasons.

Andrew Murray

The Disaster Artist is released nationwide on 8th December 2017. Read our review here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS