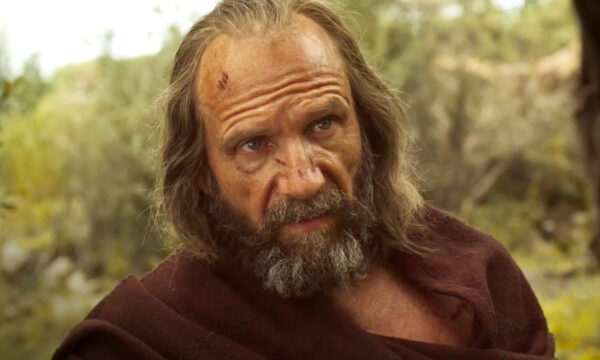

Mountains May Depart

Mountains May Depart is the eighth film from the internationally acclaimed Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhang-ke just about to hit UK cinemas. The Mandarin-language drama, originally released in China in 2015, follows the fallout of a love triangle over the course of 24 years through three distinct periods: 1999, 2014 then into the future in 2025. At the centre is Tao, played excellently by Zhao Tao, alongside Liang Jingdong as coal-miner love interest Liang, and Zhang Yi as the arrogant aspiring entrepreneur Jingsheng, who finally wins her hand in marriage. Through Tao’s emotional journey from buoyancy and optimism to pain and despair, the audience is led to explore themes of marriage and parenthood, the impact of capitalism and technology on human relationships and the future of culture and identity in an increasingly globalised world.

Stylistically the movie follows the ambitious and idiosyncratic approach of the auteur – having developed a unique voice in filmmaking, Jia Zhangke is ever experimental in look, feel and narrative. The passage of time is reflected in the movement from analog film with a retro aesthetic right through to modern, slick digital look and enlarged picture of the final scenes set in near-future Australia, and the 90s sounds of the Pet Shop Boys and traditional Cantonese singers are used as motifs reflecting nostalgia. Scenes driving the narrative are interspersed with images capturing the reality and everyday life of people in China, forming a study of how life evolved during the period through urbanisation, from the evolution of coal-mine working and rustic living to the creation of a technology-laden, phone-obsessed middle-class, finally leaving us dwelling on Chinese diaspora.

To a Western audience, the style can perhaps feel a little stilted. Long pauses in dialogue seem awkward, lingering shots contrast to the increasingly rapid, in constant flux experience that we have become accustomed to in mainstream film. A surreal quality that dominates can at times heighten the emotional intensity and at others alienate or confuse (did Tao really see a plane crash and explode at her feet? And, if so, what else was only a product of her imagination?). But to embrace the shift in pace and lack of cohesion is to appreciate the tireless and fearless reinvention that has led to Jia being admired for breaking ground in independent filmmaking, not only in in China but across international film festivals in the last decade from Platform (2000) to A Touch of Sin (2013). And while some moments can appear random or un-finessed, many hold a dark comedy in their deadpan manner or timing – a dance class of adults learning choreography to Go West utterly uninhibited is a highlight – or reveal themselves part of a carefully curated set of reference images that hold a greater significance.

A visit to Jia’s hometown Fenyang in provincial China, where the film is set, for the new auteurs festival he has created called Pingyao (even tasting the dumplings Tao creates for her son in the film) provided further context to his aims as a filmmaker: not only to tell stories but to provide a window into evolving Chinese culture as well as explore via the screen his own anxiety for its fate in the future. Mountains May Depart is deeply evocative and moving in all its eccentricity and ambiguity.

Sarah Bradbury

Mountains May Depart is released nationwide on 15th December 2017.

Watch the trailer for Mountains May Depart here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS