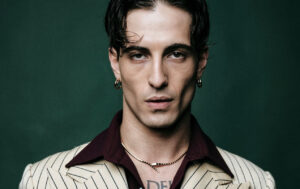

The Wound: An interview with musician, writer and lead actor Nakhane Touré

Nakhane Touré is a South African artist who has already made a name for himself with two music albums and a novel (Piggy Boy Blues, 2016), but the 30-year-old has recently entered another realm of work: acting. Starring in the controversial, divisive, but very highly praised The Wound, Touré plays Xolani, a closeted homosexual and factory worker. As a member of the Xhosa people, he has gone to the mountain to help initiate a group of boys into manhood, but his motivations are not so simple.

We caught up with the actor on Tuesday morning and spoke about The Wound and its reception, the music of Nick Drake and the fear of being offended.

Good morning, Nakhane.

Good morning.

I thought The Wound played quite like a documentary. How was it making a film that had lots of similarities to your own life?

Well, in a sense it does and it doesn’t. So, it does in the sense that I grew up in that community and I know how it runs and I understand the practice. But it doesn’t in the sense that that character is not who I am at all. I mean, I understand where he comes from and I’ve seen people like that around the community, and I guess I based him on a lot of people: uncles, and friends of uncles that I’ve seen around. So I know him, but I’m not him. You know, as you asked the question I had a picture of James Dean, in the sense that James Dean was American, and he understood the characters he played – but he wasn’t those people at all. But I guess when you’re somebody who’s outside of the culture, it seems that we’re a lot closer to a lot of people than we actually are.

Yes, the way African culture is presented to Europe is as this one thing. Even that term, ‘African culture’: it’s a continent, and there’s so much difference in it.

It’s sort of this monolithic thing, yeah, completely. For example, I was talking about this in another interview, but there’s the fact that a lot of people ask me if the depiction of the rite of passage was authentic. And I say, well that’s problematic in the sense that there are so many clans, and there are so many different ways of doing it within the different clans in the Xhosa community that there’s no one true way of doing it – so the idea of authenticity is problematic in itself.

So there’s been a lot of anger about you supposedly selling their culture. When you have that response, what do you think in terms of the insecurity about masculinity, and do you think the film undermines a feeling that is supposed to be so solid?

Yeah, I mean, talks about masculinity and patriarchy have been going on for quite a while. As great as this rite of passage can be, I think we have to look at it as a complicated thing. It can be a space where people who have not been taken seriously in the Xhosa community – boys – suddenly have a space where they can be [taken seriously], at least when they come out the other end. They can be vulnerable with each other for an entire month, and they’re in a secluded space, you know. So, there’s a lot to gain. But it’s also a space where no one else is allowed in, so whatever happens there – which is not necessarily good – just stays there; it never changes. Because no one has, I don’t want to say guts, but no one has [long pause] the courage to – not courage, courage is also a dangerous word. No one can say that certain things are wrong, because they’re alone in that space of hundreds of people, maybe – depending.

So it’s a very secluded environment?

Exactly, and being the dissenting voice can be quite dangerous, you know, because we’re very insecure.

Is that maybe part of the initiation process, working out what you can and can’t do?

Yes, because the idea of manhood is abstract – we don’t know what it is. It’s so contingent, and it’s [long pause] so contextual, and it’s ever-changing, right? The only thing that we know that we have to keep together is that men have to be at the top of the food chain. It doesn’t matter what they have to do to get there, they just have to be there. and men don’t realise how dangerous that is, not only to everyone who’s not a man, but to themselves as well, because they have this thing that they have to live up to, but they don’t even know what it is. So it’s just this whirlpool really, and everyone’s just sinking! [laughs]

Do you know what motivated the film to be made and what led you to become a part of it?

From what I hear, John and one of the co-producers had a conversation about the fact that films like this don’t exist, you know? And there was a lot of talk in continental Africa about homosexuality being, I guess, an import from Europe – a colonial import. Or something, maybe, that was foisted upon the people. Which is not true. Well, maybe the modern idea of what homosexuality is, because the word homosexual is quite modern, quite new. But the act is from time immemorial, all over the world. And it existed everywhere and everyone knew that. But maybe giving it a name, and giving it, I don’t know, its own space – its own pocket in society – becomes problematic for some people. Then couple that with Christianity. So that’s why the film was made. And also John had read a book by Thando Mgqolozana – one of the writers – called A Man Who’s Not A Man, which is about a botched circumcision. So there was this talk, I guess about queering that space, and problematising it. When I met with John he had heard my music, my first album, and he wanted me to possibly write the score – which I was very excited about – and then a few weeks later he was like, “Would you like to audition?”, and I was like: “oh, I haven’t acted in a while, I don’t know if I’m good or anything”. He said, “well, if not then we just won’t cast you!” And I’m very competitive, so I made sure that I was cast. And I was just excited – I had never seen anything like that before. Everything else was just a documentation, right, whether it was a text or a documentary on TV – which were always banned. You know after one week they’d all be taken off the screens. I’d never seen a fictive realisation of the Xhosa world, and one that incorporated queer people in the foreground, and that was interesting to me.

You found the process of making the film quite painful. Could you unpack that a little bit?

I don’t necessarily look for enjoyment when I’m making something. The process doesn’t have to evoke… I don’t have to enjoy it. Most of the time I don’t even know if I’m making good work or not. And it’s only, I guess, later on – in hindsight – that I go back and I go, “Oh OK that was OK, that was nice, I’m happy I did it”. But at the time, you’re so in the middle of it that you can’t make head or tails of it. Especially when it’s your first one. You don’t know whether you’re doing it good or not.

There’s no method?

Yeah completely, you’re just doing your best and you’re blindfolded, and you just have to trust the people that you’re working with – which is difficult, especially when you’re working with something so… tender, right? And, you’re poking it every day. Ow. Ow. Ow. And the more you poke it, you can never get used to how sore it is. Anything just exacerbates the pain. So as much as I didn’t enjoy it – because it’s a sensitive subject – I am happy that I did it. would I do it again? Yeah.

Would you like to do more acting in the future?

Yeah, I’m in no rush though. I mean, it would have to be something very different. Because I think something like this is so special and so different that you can’t repeat it. And it was the right time, right place kind of thing, and you can’t create those spaces.

The Wound didn’t feel like a story was being sold, It was more something that people have to understand.

Exactly, and it’s so specific, you know. It’s a film which could only be told by South Africans, and I guess that was what was so disappointing when the whole hoo-ha happened. Because I was like: “this was yours! It couldn’t be more yours than this”. But people react how they want to react and there’s nothing you can do about it, and I think I just have to remember that it’s their job to start the conversations, it’s not their job to be liked. But I think we’re living in a world of likes and sharing and retweeting, where people are so averse to being disliked and so afraid of not being liked.

Are people afraid of being offended?

Yeah, but it’s not even about being offended because… maybe. Maybe not, I don’t know. Offence is… wait let me think [long pause]. You have to keep people on their toes, you have to keep them questioning, and I don’t want to sound like Kanye West.I don’t want someone to give me a hug and a pat on the back when I engage with a piece of art. That’s why we have friends, you know. Art is not our friends, the world is not our friends. There’s a saying in Xhosa, you know, “this is not your uncle’s house,” but we treat it as if it’s our uncle’s house, and every time something not nice happens you’re so surprised by it. Life’s ugly, we’re animals. And maybe that’s why we’re so disassociated from our nature, and you look at wild animals as if they are so separate from us. And if anything there’s a lot to learn from them.

So what do you do to touch base with your own animal nature? Do you have a way of reconnecting with nature or are you quite city bound?

I like to think, I do, but… I was born in rural areas and I have an understanding of nature, and I have an appreciation of nature. But I grew up in a metropolis, in a suburban area, and now I live in quite an urban area, so I’m always moving around, but I’m always listening to what my ID is saying, and it never gives you a choice anyway. So without being reckless [laughs]. So instinct becomes very important in being in touch with nature. Living a little bit recklessly, and being in touch with your own wildness, and not being tame.

You’re a fan of Nick Drake.

I am.

What’s your favourite Nick Drake song, or songs?

I mean, the first Nick Drake song I heard was Kind of Magic. No, erm [sings] the one in 5/4, on the first album actually. Riverman. And I was like, what is this? and I got obsessed, I went on to the internet, I bought all his albums. Recently though, my favourite song has been Bryter Layter, which is on the Bryter Layter album. Um, the lyrics are just so beautiful, [sings] it’s just gorgeous. It’s also hilarious to me that he thought that that was his pop album, and in some ways you can sort of hear that he’s trying to make something more accessible. If only he’d waited [before committing suicide]… but it’s easier said than done. I mean, would Jeff Buckley have been as important as he is if he hadn’t died – would Jimi Hendrix?

In a way, it’s a good career move.

It really is, you just have to believe that those people can see it from other realms, you know, otherwise they get no benefit from it [laughs] – from dying.

Nakhane, thank you very much for your time, it was great to meet you.

You’re welcome, it was good to speak with you.

Ed Edwards

The Wound is released in select cinemas on 27th April 2018. Read our review here.

Watch the trailer for The Wound here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS