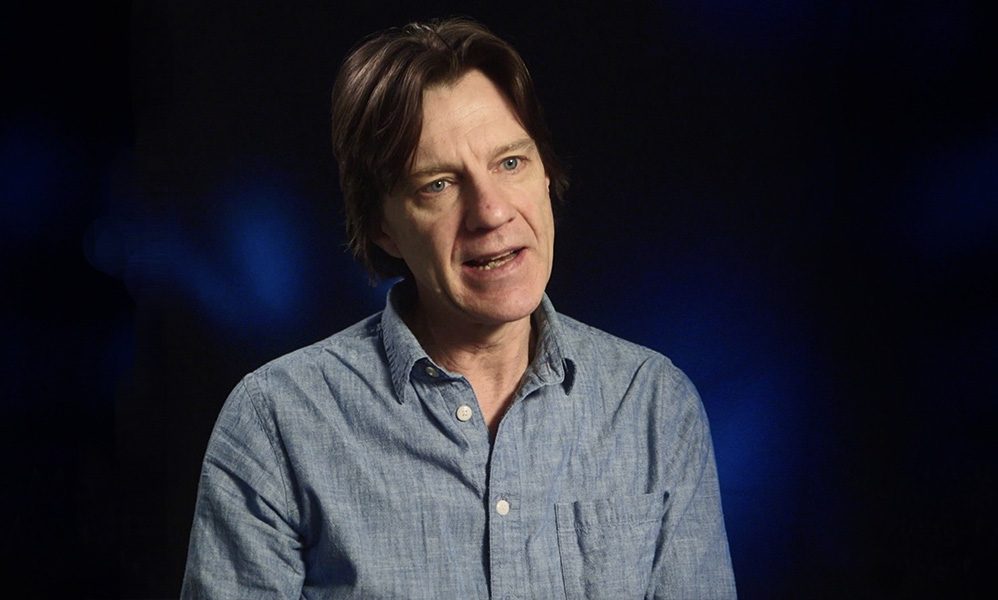

The Mercy: An interview with director James Marsh

In his follow-up to the Oscar-nominated The Theory of Everything, director James Marsh is back with The Mercy, telling the strange, nautical tale of Donald Crowhurst. A man from Teignmouth hitting an existential crisis, Crowhurst (played brilliantly by Colin Firth) sets off to sail in the Golden Globe race around the world. But his inexperience and lack of appropriate materials for the boat bring him to the edge of giving up. Instead, he reports false co-ordinates to make it appear as if he’s hitting all the records. But spending months on a boat, with nobody for company, gradually sinks him into madness.

The Upcoming was fortunate to speak with James Marsh about the film – discussing his research into the real Crowhurst, his inspirations and his last collaboration with Jóhann Jóhannsson.

When did you first become aware of Donald Crowhurst’s story?

I was aware of it, like many people, as a story you’re imbibed at an early age.

I was aware, in a more focused way, when I worked on a BBC arts show called Arena. They made a very interesting little short about Crowhurst as part of a season of films about radio. It was about his use of the radio, and the deception he undertook. I reconnected to it via the Deep Water documentary, which I really liked. That spawned our version of this story. It’s a myth, essentially, and each generation wants to tell that story in their own way for its own reasons. It resonates in very different ways depending on where you are, culturally or otherwise.

How deep did the research go in terms of Donald’s experiences of being alone on the boat?

It went for me, and Colin [Firth] even more so, in a very different way. We both became really invested with the story, and there’s lots of stuff you can read about it and try and understand about it.

I also read quite a bit of literature about isolation and what that does to the human mind. It’s really quite sobering and scary research because there are many people in the world who are in prison, in isolation. It’s incredibly damaging to your psychology and character to be cut off from other people. I’d knocked into this – a little bit – in Project Nim, a documentary I made, where chimpanzees were also like us: social primates. If you cut them off from other chimpanzees, they go mad within a couple of days. It’s incredibly disturbing. And we’re the same – perhaps we cover it up better.

I was intrigued by that part of the story because that’s the heart of it. His madness, his unravelling, comes through isolation and then you compound that with burdens of the deception and the burdens of being found out. He went to try and test himself and he found out that he wasn’t up to that test. He couldn’t do what he thought he could do. It’s like making a film really [laughs].

I like true stories because you can do lots of research on them, and it takes you back to being a documentary filmmaker. There [are] so many things that you can explore, so many things you have to learn. There’s lots of research to be done, and I really relish it.

In terms of preparing Colin for the role, was there anything you had to do to get him into the madness of Donald Crowhurst towards the end of the film?

Colin is very self-motivated, as all good actors are. He doesn’t need me to tell him what to do.

There were some very technical preparations we had to do, which was to stick him on a boat and get him to be able to sail that boat, which he did rather well. Separately from the work I was doing, Colin was spending time learning the rudiments of sailing. He did that and he was good at it. Actors tend to be good at learning new things. He had to lose some weight as well – the real Crowhurst got a lot thinner on the journey. But most of Colin’s preparation was just the stuff actors do for a role.

Colin [and I] did lots of reading of the diaries and the logbooks. And there’s a great book called The Last Strange Voyage of Donald Crowhurst [written by Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall] – we both found that book to be incredibly informative. There was lots to comment and think about. We’d have endless conversations about it too, about what the final words mean [“It is finished – It is finished IT IS THE MERCY.”]. It’s not right if I have to force him to do any preparation. Like Eddie [Redmayne, The Theory of Everything], he couldn’t wait to get on with it.

This is a film set mostly at sea, mostly with Colin by himself on the boat. Were there any specific, boat-related movies that you took inspiration from?

You have a kind of film playlist you dip into as you prepare for a film. I watched Knife in the Water, the Polanski film. He’s very good [at] shooting confined spaces. You see it in Repulsion as well, and Rosemary’s Baby. Whatever you think of him as a human being, he’s a technically brilliant filmmaker.

I also watched Apocalypse Now, which has two interesting overlaps with our story: it’s a story about people going mad, and it’s set on a boat. I watched Aguirre, Wrath of God as well, which is another story of people going into a state of disorder and chaos and madness on a boat journey.

Those were a few films that were important to me on a creative level. They were inspiring in their psychology.

Eric Gautier’s cinematography is very scenic and picturesque, presenting an exceedingly pleasant version of England. But given the reality of British weather, were these images hard to shoot?

You have no choice really, you have a schedule. We were lucky. We shot in the spring and summer. You make your own luck, and try and organise it the best you can. The difficulties are with continuity. The biggest challenge we had wasn’t shooting on the boat, [it was] the departure scene from Teignmouth. Because of tides and people involved and sticking your lead actors on boats – that was really difficult to do. And we needed the weather to be reasonably continuous. We get away with it because it gets more and more cloudy as the journey unfolds – by the end it’s gloomy, which tracks with the story. It’s ominous.

The Mercy was one of the last films Jóhann Jóhannsson composed for. What was it like to work with him?

We were friends before we worked together. We met a long time ago on a documentary project I was a consultant on. We stayed in touch and talked about work I was doing, work he was doing. And The Theory of Everything came up and I really wanted him to do it. I was able to get it by the producers, who’d never heard of him because he’d just done Prisoners and it hadn’t been released yet. They got reassured by the fact that someone else had used him in Hollywood.

So we did that score together. As you work with someone, particularly in this kind of collaboration, you become quite close because you just do. He was a very nice person and I liked his company. We had a strong personal relationship that kept going beyond The Theory of Everything to The Mercy. We had a friendship and a close one. To have heard of his death on the day The Mercy opened was a very bitter thing. I was in shock and inconsolable about it. We’d lost an incredibly talented and brilliant composer, and all the music he carried within him had gone too. It’s a terrible loss on a personal level and on a creative, professional, musical level.

The Mercy was a more interesting collaboration because it was a story that we were immediately in-sync with, both being quite dark and gloomy people. He began writing ideas before we’d shot the film. He’d be inspired by the script. The Mercy is one of three films that carry his last work. Mary Magdalene is another film coming up. He’s left a lot of amazing work behind – there’s some small consolation in that.

Euan Franklin

The Mercy is released on DVD and Blu-ray on 4th June 2018.

Watch the trailer for The Mercy here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS