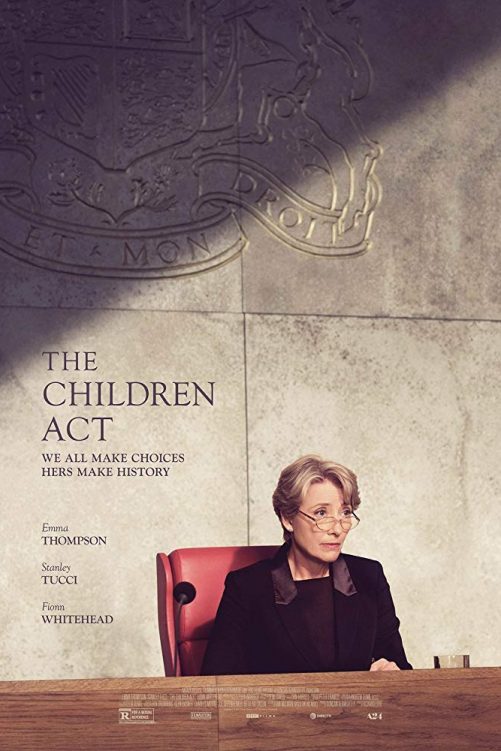

The Children Act

Long before we see the hospital monitor, it’s clear that this is a film with a beating heart. Be it the weighty knock on the courtroom door before the final verdict; the incessant tapping of keys late into the night; the heavy thud of resolute footsteps; the haunting, funereal chords of the piano; or the final beeps of the BBC World service as it flatlines through another sleepless night, there is an ever-present pulse. And pumping the lifeblood round every scene is the incomparable Emma Thompson.

Directed by Richard Eyre and adapted by writer Ian McEwan from his novel of the same name, The Children Act follows Justice Fiona May (Thompson) as she becomes entangled in the toughest case of her career. When 17-year-old Jehovah’s Witness Adam (Fionn Whitehead) refuses a critical blood transfusion due to religious beliefs, the high-profile judge is the only one with the power to legally enforce the procedure. But May soon finds her own life inextricably bound with the teen’s, and as her profession eats even more into her personal life her marriage finally begins to tear apart at the seams, her husband Jack (Stanley Tucci) unable to bear his wife’s emotional absence.

As a woman holding fort under the weight of decisions that would crush many a mere mortal, Thompson is a force to behold. However, it’s what’s behind the facade that truly captivates. Her expressions vibrate with pain, compassion and comprehension. Her eyes listen intently, and yet her own emotions are constantly suppressed, simmering gently below the surface. Every stubborn silence is excruciating, and when the floodgates finally burst, it’s almost impossible not to follow suit.

Whitehead’s Adam is enigmatic and engaging; his paradoxical youthful yet world-weary energy continues to intrigue throughout. His identity is unsettled and we can’t put our finger on him. Tucci also gives a powerful supporting performance as the frustrated spouse, treading a nuanced line between victim and villain. His presence is understated, his absence palpable.

The narrative loses its way a little during the second act. The film’s message becomes clouded as the story transitions from courtroom drama into something far messier – but perhaps this lack of structure is the point. McEwan’s screenplay is cunning and elusive; it poses many questions and leaves you to grasp at answers. What is more valuable: a human life or our right to end it? May states firmly that “this is a court of law, not a court of morals”, but as the narrative develops, an idea of what is just and “right” becomes unattainable – irrelevant, even. The published word is no longer a sufficient way to express reason; scribbled poetry replaces official law books.

Eyre employs music in a similar way. When Thompson’s character rediscovers piano as a form of expression – as something more than just a perfect performance – it becomes deeply poignant. Her vulnerability is beautiful. And the same can be said of the story: it’s not supposed to be neat and polished, but as raw, unwieldy and complicated as life itself. The Children Act is an ethical quandary which denies satisfaction but which reconnects us with something far more important: our humanity.

Rosamund Kelby

The Children Act is released nationwide on 24th August 2018.

Watch the trailer for The Children Act here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS