“Passive populations are dangerous”: The Mountain director Rick Alverson discusses the importance of challenging his viewers

US Director Rick Alverson is known for straying from conventional structure and dialogue. His latest piece of stimulating and beautifully shot cinema, The Mountain, attempts to subvert our expectations even further. The film is set in various psychiatric hospitals in the 50s and features love, lobotomies and an impressive cast including Jeff Goldblum, Tye Harison and Denis Lavant.

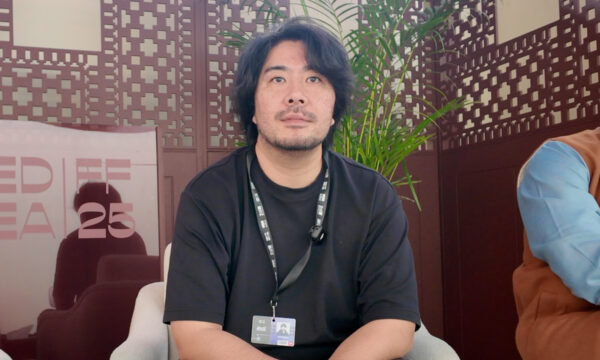

At the 75th Venice Film Festival, we spoke to the director about the need to keep his viewers on their toes, his scepticism with regards to cinematic convention and the importance of tempo and music in his work.

Why did you want to make this film?

A lot of my films are anti-Utopian because they are a counterweight to an overabundance of hyperbolic positive messages in cinema and the media, particularly in the US, that are all aspirational, that present a narrative of unlimited potential and boundless opportunities, things that are really vital for societies that are deprived of resources and hope. In cultures like the US and Europe, with an amount of privilege and a disproportionate amount of the world’s wealth and wellbeing, using these utopian narratives constantly in cinema or media and entertainment, there’s a surplus of that. It’s dangerous; it disconnects us from the world’s limitations, the fact that limitations make up everything around us, that they let us comprehend the beauty of the world but also our place in it, and without them, we become disconnected from things, we don’t understand anymore. The idiocy in the US of government people denying the global warming is real is a byproduct of this complete disconnect from the actuality and physicality of the world. It’s the narrative that we are unbound by these constraints. The film is about constraints and limitations.

Has the perception of mental illness changed?

There was a lot of ignorance about what mental illness was. The characters are loosely based on Walter Freeman who invented lobotomy based on a Portuguese procedure called leucotomy. He performed it on thousands without a licence to perform surgery. It’s an arbitrary fussing with the pre-frontal lobe, severing connectivity to essentially pacify people and reduce their capacity for emotion and agitation. But it was done to homosexuals and to women in menopause. It was done to pacify segments of the population, and that was partially out of ignorance, partly out of arrogance. It was predominantly white males that were imposing this segregation.

How did he get away with it?

Today you commit a crime if you don’t commit yourself voluntarily, but at that time you could put people away, and once you were in those institutions it was a free for all. You could take anybody and there were all kinds of medical experiments and oddities that were done on those populations.

I mean the irony of it all was that he believed there was a physical, chemical component and not a psychoanalytical component to mental illness, and he was right about that, the pharmaceutical corporations realised the same thing. They were able to do a cleaner… they didn’t have the collateral damage that he had.

There’s a wonderful John Cage piece, as slow as possible. Is this your kind of approach, to make a movie as slow as possible.

I would love to make movies like John Cage made music.

How did you find the right rhythm?

I think there’s an artificial quality to the film, to the blocking staging, the shooting, even the performances ultimately. I want people to deal with the material of the film. It’s silly but something I hate in cinema is when the author speaks through the characters. It’s not the character speaking, it’s the author. For some reason, I’m irritated by so much in cinema but metaphors particularly drive me insane, and allegories. But this movie is just all metaphors, allegory and me speaking through the characters. It’s raw building blocks, because I didn’t understand those things that irritated me so I wanted to engage with them in different ways. For instance, there’s Lavant: this isn’t a mountain, it’s a picture. That’s pointing to the formal. Let’s be aware of what we are contending with here. What is the delivery device? Don’t believe everything, don’t be narrative and content obsessed. Where am I? what am I looking at? What’s it composed of? Am I being told something? Am I not? What’s my experience? People don’t watch movies like that any more.

When did they stop?

It’s been a gradual thing. In a popular sense, they don’t because cinema stopped having that mission statement, it became a device to deliver very comfortable consumers. Corporations own studios, there’s a reason for this. You can create passive consumers and engineer your consumers to want certain things through these narratives. When you are in a cinema or home watching a movie in the dark, we are more vulnerable than we think we are. We think: I’m an adult, I can assess what’s real. But we are taking in something delivered to us. I think we’re susceptible.

What films gave you this feeling?

I’m not gonna name names. The majority of promotional cinema operates by these rules. It’s trying to validate the audience’s worldview. It wants to make the audience comfortable. The audience can’t be challenged or they won’t consume properly. This is the conventional wisdom, but I don’t think it’s true. I think that those passive populations are dangerous for us all. I think that if you have stimulated viewers, they want different content, they want different form, they’ll be a more discerning populus. When I was 13 I watched the first Indian Jones and I walked out of the theatre and I felt like Harrison Ford’s face was my face. It was a frightening intoxication that I realised had an almost physiological effect on me and it was a powerful, important experience.

Why did you choose European actors?

I started watching arthouse cinema when I was 16. My aesthetic tendency is in that direction and I love those actors, so I want to feel culpable. This would be very one-sided if I made something that didn’t appeal to me. If it appeals to me then I have to wrestle with it. It’s a cat and mouse game. It was difficult to make for that reason. It was a struggle to understand how intoxicating this is.

How did you conceive of getting these guys together?

The process of developing a film is long and cumbersome. There are many iterations and for me its a discovery. Ultimately you settle on particular faces and at times, there are availability issues. But ultimately, I wanted to work with them all. The tone of the film changed with my considerations of the cast. I could have made a different movie with a different cast. I want to work with and against the attributes of the actors.

Did you discuss Spielberg with Tye Sheridan?

No, Tye understands my scepticism of the form though.

What is the role of sexuality in this film?

Sexuality is one of the few building blocks of cinema and literature, particularly the coming of age story. It interests me, the idea of sexual maturity. There are all these romantic notions of arrival. In a male sense, someone loses a virginity and they are an adult. This idea of arrival, It’s a utopian idea, complete fiction to me. This idea of something perfect, that you can actually step into something that’s stable. That doesn’t exist. The film uses the coming of age story and the losing your virginity because of that arc and the temporal movement of it, but also the possibility of union with another, this is the hermaphrodite of antiquity in the film. A representation of the utopian idea of the perfect union, something that was before us and something that may be possible. It dovetails with the Mountain. And that’s based on the Lumarians, who were luminous hermaphrodites. It doesn’t matter to me that people don’t get those references, I’d almost prefer that they didn’t.

Are there other filmmakers you share your scepticism with?

Yeah! There was a moment when there were some really vital, sceptical cinema. The sort of Michael Haneke, Bruno Dumont, Clare Denis… there was some really challenging cinema there.

But do you have an active dialogue about this with other filmmakers?

I live in Richmond, Virginia, I don’t get out much

Do you feel safe, with the Trump effect?

It’s a crossroad for a young country’s democracy. There’s something very palpable. This is a problem with this aspirational, disconnected, utopian American thinking. The majority of the Americans believe democracy is not affected by this, that it will be around forever. The historical context is that democracy is incredibly young. We are at a crossroad. Unless people are thinking about and approaching politics critically, it could go very bad. It’s on everybody’s minds.

You are also a musician. Do you give importance to the film’s musicality?

This one has a very strange rhythm that I got into. The beginning is so staccato it feels problematic, then it moves into these more comfortable tempos. I think the beginning of the film is like an uncalibrated metronome. It’s all information: this is the life of the boy. I think of editing in filmmaking structurally, and even musically. It’s all about tempo and our expectation of tempo. I made a choice to cut off tempo, and it’s so unsatisfying and I did it with glee, and it could have been… you know… but that’s part of the initial statement.

When Udo Kier sings the German song, was this his idea?

My early films didn’t have scripted dialogue. This is all scripted apart from that number and Jeff’s German song. Udo brought this song from his childhood. I think of those things tonally. My early films were all dialogues, even two films ago, The Comedy, the so-called improvisational/reactionary. I liked working like that: with dialogue, tonal cadence and gesture…I wanted to listen like a child would listen to people talking about taxes and not understanding. It contained all these hidden messages. The formal way children engage with the world is really interesting. So I try, when I can, not to pay attention to the delivery mechanism. So many films are indistinguishable from literature.

Jeff’s character’s role is very different in the scientific field. What made you think he would be suitable?

He is incredibly intelligent, he’s been cast more than once as a doctor/scientist. That interested me. People deal with the context, not only what is in front of them. The Fly is tethered to The Mountain, there’s Jeff in it. If you think it’s separate you are naïve. That interests me a lot. I like people to say: of course, Goldblum is a travelling doctor.

Do you like when people say there’s a problem?

Yes, it means there’s a question. They are engaged. I want them to be active. There’s a surplus of anaesthesia and narcotics.

Denis doesn’t do much English language cinema?

Just two films before this one.

Is it hard to get him to agree and how was the work on the set?

We had to speak largely through translators. Then it was gestures and laughs. He’s way [a] better [English speaker] than he pretends. He goes in and out of English; I left it up to him. Sometimes I said: I want this line in English, but other times I said, go at will. But he was a force of nature and a very sweet man and he responded to the work.

Can you tell us about the balance of beauty and cinematography

I want it to be intoxicating and satisfy our expectations about beauty in film, but then I’m interested in that threshold: going of the film and being pulled out of the film. If that can happen a lot, I think it’s a very accurate experience and people are engaged in a more formal, rich way. I like that movement. I need to have something inviting, but it’s so formal that it’s like walking into a party and seeing all these beautiful people and the lighting is perfect and then you mingle around a bit and realise the entire room is full of a load of mannequins. That’s the experience I want. There’s something stale about the film formally. It stops being rich at some point and the beauty of the film is broken a little.

How hard was this to get funded?

I don’t know if it’s tough for Europe, but in the States it’s dead, and there’s a few very brave studios and financiers who realise that the ship is sinking because we’re milking the mediocrity of it and we need to have, for political and social reasons, something risky and brave and vital, or it’s over. I think there’s a duty to do that.

In this film, we are playing with a whole palette of people’s expectations and subverting them to engage with the viewer in a problematic way. But I still want people to feel that they recognise the film, that they are comfortable and welcome.

Filippo L’Astorina

The Mountain does not have a UK release date yet. Read our review here.

Read more reviews from our Venice Film Festival 2018 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Venice Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS