Cairo Film Festival 2018: Beckoning in a new era for this international festival

This is the 40th edition of Cairo International Film Festival (CIFF) and the general feeling is one of regeneration. Recent years have not been kind. The 2011 and 2013 editions were postponed due to a mixture of budgetary constraints, managerial incompetence, political pressure and national instability, while turmoil, uprising and terror have damaged a once vibrant tourism industry in Egypt. The UK Home Office currently advises against travelling. Other festivals in Marrakesh and Tel Aviv have meanwhile increased in popularity. Yet against this backdrop CIFF has attempted to reinvent itself and reclaim its place as the premier film festival in the region.

There is a new hand on the tiller: Mohamed Hefzy, a renowned screenwriter and producer who, at 43, has become the youngest festival president in the event’s history. A B Shawky’s Yomeddine, which Hefzy co-produced, featured in competition at Cannes this year. By most accounts, he has added fresh drive, ambition, impetus and – importantly – contacts. There are new expectations, and these have been reasonably met.

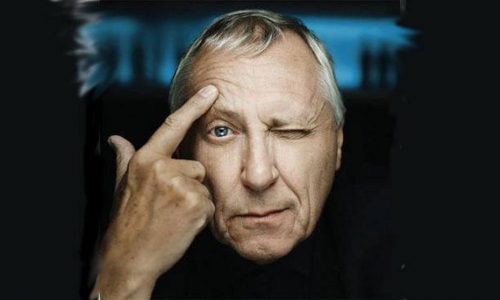

The opening ceremony was indicative of much of the festival: opulent, celebratory and, ultimately, sparse. Many honorary and excellence awards were handed out, with leading figures in Arabic cinema recognised and admired. Our own Peter Greenaway – now popular anywhere but in the UK – collected an achievement gong, and offered himself as a garrulous figure over the first few days. The esteemed director would deliver a masterclass on cinema the following morning, while declaring the medium’s very death. These masterclasses are becoming ever-present in festival schedules and encourage strong attendances.

Back to the ceremony, and after innumerable laurels had been distributed, the opening film screened, Peter Farrelly’s Oscar-tipped Deep South race drama Green Book. Most of the audience – mainly local celebrities – filtered out for the poolside dinner, leaving only a few hardened hacks behind. There would be mixed numbers for screenings throughout, but this feels like steady progress given the preceding years. CIFF is at the beginning of a restructuring; there is no immediate panacea. Prestigious guests helped. The consistently excellent Palestinian filmmaker Annemarie Jacir, whose latest Wajib has recently received international acclaim, arrived for the latter half of the festival. As did Ralph Fiennes, who promoted his third directorial effort The White Crow with his usual brooding and bombast.

Oscar-winning Danish director Bille August led the competition jury, in between working on his much-delayed Gianni Versace project. August ran the rule over a strong selection, awarding the Golden Pyramid for best film to Alvaro Brechner’s A Twelve-Year Night, based on real events that took place at the start of Uruguay’s military junta in the 1970s. We follow three guerilla fighters through the travails of political imprisonment. Best director was awarded to Thai debutant Phuttiphong Aroonpheng for Manta Ray, a lyrical, elegiac, sometimes experimental tale of a fisherman and a mute migrant, one that offers a timely dedication to the plight of Rohingya Muslims, those displaced, fleeing and trafficked across South East Asia. These were worthy winners, politically potent and artistically impressive.

International premieres were few – only 15 out of the 160 screened – but strength and diversity existed across the board. Some 59 countries participated, and big names such as Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Sergei Loznitsa’s Donbass – festival hits at this year’s Venice and Cannes, respectively – brought in much excitement and chatter. Roma, unfortunately, was shown without English subtitles. Juan Vera’s An Unexpected Love, boasting two excellent performances from Argentinian stalwarts Mercedes Morán and Ricardo Darín, was unjustifiably long but generally agreeable, an amusing, warm late-life study of relationship apathy and newfound sexual appetites. The Argentinian embassy had the press on board with a suitably plush drinks evening.

To experience the festival as a journalist was, frankly, joyful. Put up in a luxurious hotel in the centre of Cairo beside the Nile, offered complementary trips to the Pyramids and the Egyptian Museum, welcomed “home” by the unfalteringly helpful and polite hotel staff – this was unnerving comfort. It spoke to a desire to rejuvenate the festival and, with Hefzy beckoning in a new era, capturing new and former glories looks eminently possible.

To the eye, however, two paradoxes must be considered. First, Cairo is a dense, suffocating, overpopulated metropolis. There is no excuse for empty seats in screenings. Local people should be encouraged to attend, whatever the concerns over safety or prestige. To foster a lively cultural community is both a top-down and bottom-up exercise. Second, the Arab female director’s section, including, among others, Kaouther Ben Hania’s Beauty and the Dogs, was welcome acknowledgement of women in the industry. Such advancements are offset – at least in immediate perception – by the absurd, terrifying decision by state prosecutors to interrogate Egyptian actress Rania Youssef for wearing an “obscene” dress during the closing ceremony. This, of course, is not the direct fault of the festival. But it is the leading headline as we stand. Draconian measures such as these do not help CIFF’s global standing. Given the innate patriarchy bound up within Egyptian law, these instances will not be easily overcome. So Hefzy has a challenge on his hands. This year constituted the start.

Joseph Owen

Photo: Mohamed El Shahed / AFP / Getty Images

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS