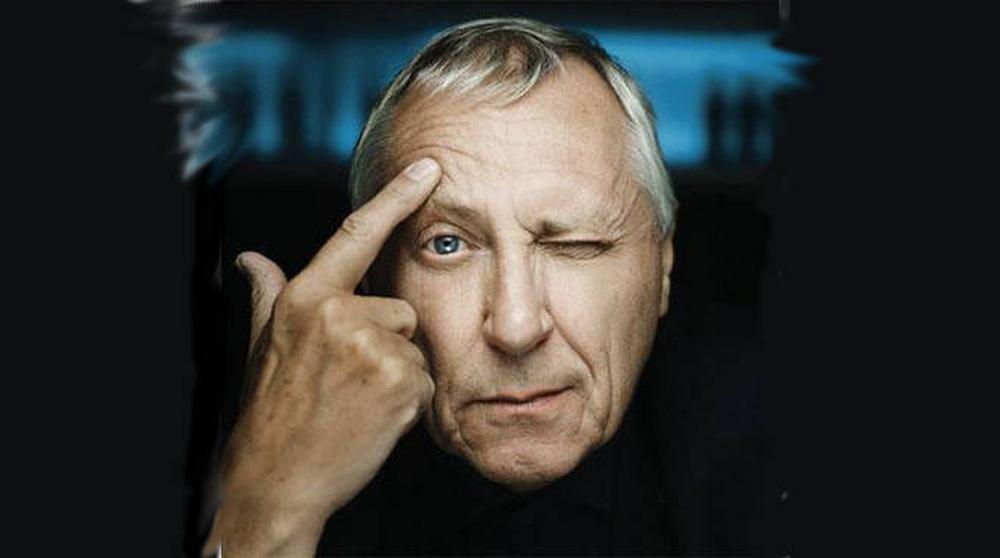

“Cinema is dead, long live cinema”: An interview with Peter Greenaway at Cairo Film Festival 2018

Legendary British director Peter Greenaway has been presented with a lifetime achievement award and invited to host a masterclass at the 40th International Cairo Film Festival.

We interviewed the revered auteur the day after the opening ceremony to talk about his upcoming projects, the death of cinema, his views on Brexit and the nature of art and history.

What’s next for cinema?

This thing in my pocket [mobile phone], which is probably in your pocket. I think the cinema of our fathers and forefathers used to be a big public event and now most people see films on a phone when they’re lying in bed, sitting in their office or maybe on their sofa in their front room. I don’t think that’s cinema. Two other things. From 1895 to 1929 there was a phenomenon called Silent Cinema. I don’t believe it for one moment; there was always sound. But where has that cinema gone? Do you watch it? Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, for children at Christmas, maybe some film academic who wants to know what Chicago tramcars looked like in 1921. So it’s become an archival phenomenon. Practically nobody at all looks at it for its entertainment value. It’s gone, it’s gone, it’s gone. Why do you not imagine a risk that cinema will go the same way? I’m sure that my great-grandchildren will say, “cinema, what was that?” So it ceased to be a public phenomenon where you go into a dark place at an event where the screen is bigger and louder than you are and you have a whole series of people around you. Those two indications will mean that cinema is dying.

Brilliant French cinematographer Jean-Luc Godard said at least 25 years ago that cinema was dying. Even stupid [Quentin] Tarantino now says the same thing but for all the wrong reasons, and all your big-name Americans are saying the same thing. These are all Johnny-come-latelys. But people like me have been saying this for a long time. But! You should not be disappointed. You should not be unhappy because what happens next will be much, much better. The technologies are increasing. Microsoft invents something new every afternoon. Out of the phenomenon of these things will rise a phoenix which will be much more exciting than anything that exists now. The full title of my lecture [his Masterclass given at Cairo Film Festival] is what they said of Louis XIV: “The King Is Dead, Long Live The King.” Cinema is dead, long live cinema.

Do you think that cinema needs to reclaim some notion of the image?

We have a text-based cinema. Every film you’ve ever seen started life as a text. I used to say “on the back of a cigarette packet”, but nobody smokes anymore, so we have to change that metaphor. The way it’s devised, and I rather suspect perhaps in a melancholy moment that you’ve never seen any cinema, and that all you’ve seen is 123 years of illustrative text and that’s not the same thing at all. Text has so many ways to hand down its meaning. We’ve had lyric poetry since Homer, for at least 3000 years. We’ve had the novel for 400 years. We have theatre which always hands its meaning down in image but not in text. That’s why it’s always continually being being revolutionised. Why can’t we have a medium that actually allows the possibilities of our primary sense – which is our eyes – to be able to communicate not ideas about ourselves but also about the world? I would have thought, along with a whole series of apologists in the 1900s and 1910s, that cinema would be the answer to that. But I’m afraid it’s been a great disappointment. We now basically have a cinema which is no more than fairytales for adults. Yes? Bedtime stories for adults.

Cinema was created more or less at the same time as when Freud wrote his first papers on female hysteria. It’s very much about female hysteria. It’s very much a deeply misogynist, unfortunate phenomenon that still plays games with psychosis and so on. It has beginnings, middles and ends. It hardly ever moves away from those notions. If you think that perhaps the most important American living director is probably [Martin] Scorsese. He still makes the same films as [D W] Griffith, in the same language, the same syntax, the same vocabulary. If you think of what’s happened from 1895 to now in literature, in painting, in music, there have been huge, huge changes of language. Cinema has been very slow in changing anything. There are lots of reasons for that. Maybe because it has become so associated with money making, money making, money making, and naturally human beings are very conservative – very cautious. Things move very slowly when the medium is so constrained by notions of power or money. Then, inevitably, cinema is not, shall we say, like impressionism or post-impressionism, which is a medium of radicalisation. It’s never going to change or it will change very slowly. I’m being excessively polemical here.

Are there contemporary directors who you think are trying to break the mould of text-based cinema?

Well there are, of course. David Lynch for a long time, but now he seems to be busy making restaurants, doesn’t he? He seems to have given up on cinema. For a time I thought [David] Cronenberg was interesting but he’s basically illustrating famous novels and being very sensational. There’s a lot which is coming out of web-making, out of cutting-edge video notions. I’d hardly say it’s coming out of the underground because the underground is respectable. I’m not sure that these guys are particularly “respectable”. So I don’t think you’re seeing a great amount of real, invigorating radicalism in cinema. That to me is a great, great disappointment.

Can you talk about upcoming projects?

Yes. We are pursuing projects always. I like to juggle many all year and if one falls foul or gets boring I can always pick up something else. But we have about eight scripts we are manoeuvering on. Some are really still on the backburner. One of the projects I’m struggling with now thanks to very, very dodgy Italian producers is about the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși [called Walking to Paris]. In 1986, he walked from Budapest to Paris. Took him nearly two years, about 1500 miles. He was so poor. His parents were farmers, and he was a shepherd boy ever since the age of five. He couldn’t even afford the train fare. So he had to walk. If you want to play games with cinema journalism, this is a walking movie, or a road movie but with walking. We’re not on wheels. Occasionally, he cheats and steals a bicycle.

It’s three things for me. First of all, I’ve made so many films recently in studios. I want to get out of that artificiality and get out not necessarily into an urban world but into a world of natural history. He travels through Hungary, Romania, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and finally France. He’s a rather sort of shy guy, perhaps he doesn’t like people very much, perhaps misanthropic. So he always avoids big cities. If he comes to a river, he would prefer to swim rather than cross the bridge. He’s always accompanied by dogs because of his years up in the Romanian mountains, which are of course close to Transylvania, from where we know all sorts of demons come from. He lives off the land: he steals chickens and eats bird eggs. He’s very good at catching rabbits so it doesn’t worry him. He can live off the land. But it’s a long journey and I’ve devised about 50 picaresque little adventures, some of them violent. We make an equation with contemporary Europe, where not so much now, but three years ago, huge numbers of people were walking, walking, walking, walking. This is the only way they could get about.

All these people are looking for a better life, and in a curious ways so is Brâncuși. You’ve got to be embarrassed to be viable as a contemporary artist: Picasso’s there, Braque’s there, Modigliani’s there, Gertrude Stein’s there. Soon the Americans will come and we have that great explosion at the beginning of the 20th century which enters us into the greatest period of art we have ever known, which is the 20th century. So it’s all about those sorts of ideas but it’s also a paean, an elegy to the European landscape before agribusiness. Just before big industries, before six-lane highways, so it’s a certain form of paradise. But it’s dangerous. Immigrants get beaten up and so does Brâncuși. But he has erotic adventures and he has one or two perhaps more sentimental, romantic adventures. When he finally gets there in Paris, Bastille Day in 1906, he takes the sculptor’s hammer out of his sack and he bangs the girders of the Eiffel Tower and says, “I have arrived.” End of film: the man who completely changes 20th century sculpture.

The other film you are working on is called The Food of Love.

Yes, that’s a quotation from Shakespeare – “If music be the food of love, play on” – and it’s really an extension of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, which was badly filmed by a certain Italian director [Luchino Visconti]. I have written this script from the original source, which is written really by two homosexual paedophiles. Basically both Thomas Mann and indeed the Italian director – you see I’m trying to avoid saying his name, which is strange, isn’t it? Visconti was regarded as the Great White Hope of Italian cinema but it was the man from the underground, Fellini, who was really the important character. I think largely we’ve forgotten Visconti now, apart from one or two academics. Fellini we’re not going to forget. He really is a giant of cinema.

Death in Venice is about a lust for a beautiful boy on the beach. And I have written a script about what happens to that boy 40 years later when he becomes an adult, with all the implications of the original material. Probably when Thomas Mann wrote the book, and certainly when Visconti made the film, they were not really allowed to talk about paedophilia. I think we can now. So maybe my film will be a little more honest about what was really going on. I have to come clean: every English director eventually wants to make a film in Venice.

How would you explain your reception in the UK relative to your reception in Europe?

The reception in Europe is far more enthusiastic than it would be in the UK. My classic answer is, and I think you would agree, that I make a very baroque cinema and the English basically don’t feel very sympathetic to a baroque cinema. They are puritanical, maybe, reticent people, not very keen to show emotion. It’s got a lot to do with religion. Italian baroque, Mediterranean freedoms, Roman Catholicism: despite all their negativity they are still very positive in a curious way. The Italians enjoy life.

As Brits don’t?

It’s the suspicion, isn’t it? I mean, look at the f**k-up we’ve done with Brexit.

What’s the view like from Amsterdam?

This is particularly germane to me now. I am determined to stay like I have been for at least 40 years, a good European. I just made an application for my Dutch passport because I live in Amsterdam and have done for about 20 years. I’m happy to say I’ve been accepted, so three cheers, I can remain European whatever the f**k happens in the UK. I can have dual citizenship. I’ve also been told I can vote twice – that sounds extraordinary, doesn’t it? Once in Amsterdam, once in the UK, but I’m going to have to test that because I don’t really believe that’s true.

Do you take any kind of creative inspiration from the current political situation?

Well, my cinema – you’ll have to agree or disagree – is more about aesthetics than politics. Somebody like Umberto Eco would certainly say that aesthetics are deeply associated with political decision-making. We cannot avoid or even afford to avoid being political. But I rather suspect you would agree with me that the Brexit phenomenon is pretty stupid. I have four children, two of them quite young, who would be benefiting enormously from being Europeans. All the sources of inspiration and finance are all going to be cut off. We haven’t had a war in Europe for 73 years. Why? Because of unity growing – ok, inadequate, full of injustices, badly made, maybe poorly conceived. But the EU is still very a very positive notion of what, inevitably, is happening to the world. Eventually it’s going to be 2080 and we will have a single world government and we cannot afford to avoid it. It’s going to be an enormous struggle. God knows what it’s going to look like. Civilization is going in that direction. Why obstruct it? People are very scared, s**t-scared, of immigration. You know I’m an immigrant: Welsh by birth, English by education and now I live in Holland, the most civilised country in Europe.

Can you talk more about your idea of painting?

My idea about painting would stem from AD 79, which is when Vesuvius erupts and pours ash and lava all over Pompeii. I have a big project in Pompeii at the moment. Since AD 79 to now we have had an extraordinary heritage of amazing image-making. It’s big and vast, and when compared, cinema is rather immature, infantile, still an embryo. But don’t worry about it because it’s dead already.

Can I ask about the Pompeii project?

You might know there has been a new injection of money into Pompeii and they’re discovering all sorts of amazing things. So much so, they have to reconsider the actual date of the explosion of Vesuvius, which is extraordinary. I understand some amazing things are going on here [in Egypt] about how the pyramids were built. Even last week, excavations created new excitements. I’m not particularly archaeologically minded but I do read an awful lot of history, and out of the 16 feature films I’ve made, about six of them are very much about historical dramas.

But good history was always about the present, not really about the past. When the greatest English historian [Edward] Gibbon wrote Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, it was really about England. He’s not talking about Romans at all. I think that’s always true. Historians always have vested interests. Julius Caesar, Winston Churchill, both beginning with the letter C. They weren’t really into history; they were into subjective opinions about their own attitude towards life. There’s no such thing as history; there’s only historians. How can you go back and judge? Historians are human and – let me repeat – have enormous vested interests, I mean certainly to earn money, certainly to please a patron, maybe to be put on the map. No one disagrees that the desires of all people who write – here’s a man who writes [gestures expressively at this journalist] to be read. I would argue –this is not original by any means – that history is only a branch of literature.

Joseph Owen

For further information about the festival visit the offical website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS