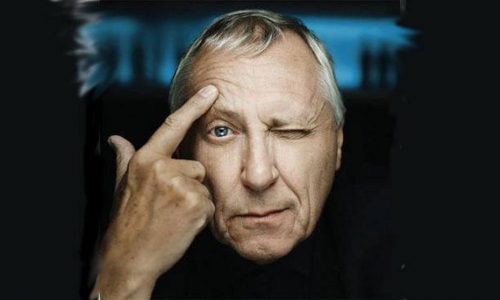

“Movies are emotional; it’s not an intellectual medium”: An interview with Bille August at Cairo Film Festival 2018

Legendary, Oscar-winning Danish director Bille August is president of the jury at the 40th Cairo Film Festival. We interviewed August the day after the opening ceremony, where the director spoke about his life’s work, leading the jury, working with Bergman and his views on the film industry.

Is the Gianni Versace project, The Emperor of Dreams, still happening?

Finally it’s on its way. I’m so happy we’re working on it. Sometimes it just takes time before the casting and the money is there. Sometimes you work on it for years and all of a sudden it comes together and I think this one will happen next year. I can’t tell you the cast yet!

Have you seen the TV version [The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story]?

This is very different. This is about the life of Versace. The TV version is more about killing and the focus is more on the murder. [The Emperor of Dreams] is completely different. This is a story about the relationship between his three siblings: Donatella, Tina and Santo. It’s a family story.

Were you glad to see the TV version turn out as it did?

I only saw a short clip from it because when you work on a story it is just confusing to see another interpretation. So I didn’t really see it but, as I said, I understood it was a scene from the killing, a murder mystery. This, however, is a family story and also how they build up their empires. It’s very different.

You had a film here in Cairo 20 years ago. What is your relationship with the festival?

I have been asked a couple of times to be the president of the jury, and I just didn’t have time. It depends always what you’re doing at the moment. But this year I had time. So I’m excited to be here. I think it’s the most important festival in the Arabic and African part of the world. So I always wanted to come here and I hope the films are good. You never know with festivals.

Do you have criteria for judging the films? What do you prioritise?

Being in a jury is an important job because it means a lot to those who get prizes. So we really take it seriously and see the films without any prejudice. Just watch [a film] and let your heart decide. Because, after all, movies are emotional; it’s not an intellectual medium. Of course, there has to be some cinematic value.

What are your thoughts on Italian cinema?

There are some very good and interesting directors. I understand it’s tough to get film financing if it is based everywhere, especially for the kind of films that we like. You know you can always see that an Italian film has a signature. I saw a film set outside Napoli about a man who has a dog [Dogman]. Wonderful. And I like his [Matteo Garrone’s] films a lot. This kind of film always has a signature. They have great directors in Italy.

What is the type of film that you like?

There has to be a story and it has to be some kind of a drama, something that engages you. But it also has to be about something. It has to be meaningful. It has to have substance. Personally, our life stories are about relationships that we pursue. It has to be cinematic.

Can you talk about your recent film 55 Steps?

We did the film two years ago and it’s opening now in the US. It’s a case story that takes place in San Francisco in 1989. It’s about a mentally ill patient who is played by Helena Bonham Carter [Eleanor Riese]. She’s overdosed, she wants to get out of medicine, out of the hospital. So she hires a lawyer, played by Hilary Swank, a very efficient, business-like woman to help her to get out and sue the hospital system and the medical industry in the US. They eventually finally win the case and it changes the whole way of giving medicine to patients in the US. It is a great way to beat it. But most of all it’s a story about a very rare and unique friendship between this mentally unwell woman and an official, business-like woman. It’s a yin and yang story. They became very good friends even though they were so different. Both the actors are wonderful and give great performances. It opens in the US now.

Fellini was one of the reasons you became a director. Can you talk about that?

When I went to school in the 50s, a long time ago, once or twice a year the school went to the cinema to see films and most of the time it was all these very bad American westerns. Once they made a mistake, I don’t know why, but they were screening La Strada and no one understood anything. We were only kids but I loved it so much. There was something about it and I just remember I thought that maybe one day I could do something in this kind of world. It was a big change for me.

In the UK you’re best known for Pelle the Conqueror. Why do you think that film resonated so much internationally?

It’s a love story between a father and a son. And it’s a story about immigrants, a very poor man who has absolutely nothing but his strong hands to work with. But it’s about the way he takes care of his son and the love for his son. It is about how the father is such a pillar, to help his son grow up and become a strong person. It’s a simple story. It’s very emotional and a vast film as well, an epic film. The film I just finished and is opening in Denmark is similar, called A Fortunate Man. It also has an epic quality.

What was it like working with Ingmar Bergman on The Best Intentions?

I always admired Ingmar Bergman for his work. For me, he was one of the greatest directors in the world. What I liked about his films was that he so easily moved into the space between dream and reality, where no one else goes, where most of our efforts fail. He did it in a very simple way without any effects but still went into this world. I really admire him for that. Then one day he called me. He said that he wrote this story about his parents. He asked if I was interested. Of course I was very interested and as I read it I found an amazing script. Then I met him and I was a bit nervous because I didn’t want to be his assistant. I was afraid that he would interfere too much, but he said he had directed more than 50 films himself and knew the importance of the integrity of the director and screenwriter. Then we worked together for half a year on the script, talked, and I stayed on this island; this was a wonderful time. Since then I kept a relationship, every Saturday, two o’clock he would call up. He was a very precise man. So when he died and I lost him, I lost somebody I love.

Were there anxieties or complications about adapting such an autobiographical story?

It’s just a great script. I mean he’s just an amazing screenwriter. Even though his films are not plot-based, in long dialogues there’s always a sense of drama. You know it’s amazing where there’s a great screenplay.

Do you find that there are differences between shooting in English and shooting in your native language?

It’s really no big difference. I don’t see it. Of course, when I work in my own language the words comes faster. Sometimes when you work with actors and do a scene and you want to do it again, you have to explain to the actors why they ought to do it differently. Sometimes you miss that. But most actors are clever people. I would never move to the US. I spent a lot of time in LA and it’s just a crazy world for me; it’s too superficial. It’s all about making deals and money and it’s easy to lose your identity and integrity in the US. Danish directors have decided to make their lives there and I can just feel the way they’re talking about the films. It’s a completely different process if you’re in that environment every day, and it’s boring. It’s so superficial. It’s also because there was a period in Hollywood where the studios were at least interested in doing alternative films filled with subjects. But they bought these small film companies like Miramax; they bought these small companies and decided [they] didn’t make money.

What’s your view on the way the film industry is going?

I think it’s interesting that all these television and streaming services are also making feature films, and if they can find their way, which they’re starting to do now. Films are being released in cinemas theatrically and also have the possibility of being purchased later for streaming. It’s a good combination and it’s the kind of thing that offers an opportunity to get the money back. I think that’s where it’s going.

You think this approach offers creative control as well?

Yes. Exactly. I’ve been offered a couple of projects and they keep saying we want to do something different. We know that the studios want to re-enter at this point. And I think that that’s the way it’s going. It is always expensive to make films and you have to find the money to release the kind of film I’m interested in. It’s tough to find. You have financing totally unacceptable releases, so therefore in Europe you have this support system where you get a lot of help from different funds and there is a big audience for this kind of cinema.

Which British directors do you admire?

I know Ken Loach very well. He’s a lovely man. He always managed to make these films for a very low price and with no big names. So he can continue to make a lot of movies even though it’s a small audience, because he’s cheap. It was the same with Ingmar Bergman. He made all these films in the 50s and 60s. He could only afford to make a film with three actors. That’s why he made all this money. So he wrote scripts for three people. So that’s how to do it; it’s the same with Ken Loach, who I love for his earlier films like Kes and Family Life. I also like [Lindsay] Anderson who made If…

Danish drama was very popular in the UK for a time. Are you a fan?

I don’t watch television. But they’re well made.

Joseph Owen

Photo: Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty Images

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS