Monsters and Men: An interview with director Reinaldo Marcus Green

Monsters and Men is the compelling debut feature from Reinaldo Marcus Green, whose focal point is the fatal police shooting of an unarmed African American man in Brooklyn at the hands of a white cop. The movie earned the director a special jury prize at Sundance for Outstanding First Feature.

The film’s narrative takes on a unique triptych structure, passing between the perspectives of three men of colour in the aftermath of the incident: Manny Ortega, who witnesses the shooting, films it on his phone and must decide whether to share it; police officer Dennis Williams, who grapples with whether to risk his career by speaking out against his colleagues; and a talented high-school kid, Zyrick, who has a baseball career in front of him but feels compelled to join his community in protesting the wrongdoing. The three central performances are crucial to bringing depth and fostering empathy with the characters: Anthony Ramos (A Star is Born, Hamilton) as Manny, John David Washington (son of Denzel and actor in Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman) as Williams, and Kelvin Harrison Jr (Mudbound) as Zyrick.

Stunning cinematography, skilfully managed tension and a carefully chosen cast deliver a subtly powerful and provocative study, not only of racism and police brutality, but more broadly of action vs inaction, asking the audience throughout: what would you do?

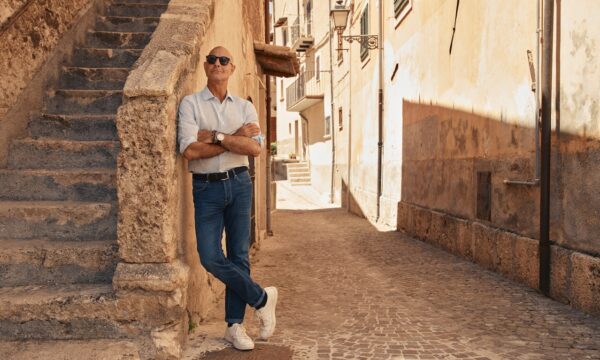

We sat down with director Green to hear about why he chose this story for his debut feature, what he wanted to achieve with the film and what he hopes people will take away.

Hi Reinaldo, thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us. Monsters and Men is a brilliant and eye-opening film that’s been honoured with the Special Jury prize at Sundance, so congratulations first of all. Why did you choose this particular story for your debut feature?

I made a short film in 2015 called Stop and the route I chose was to do a short to feature. I was really resistant to the idea at first. [Stop] is about a young African American kid walking home from practice who gets stopped and frisked by the police, and it worked as nine minutes, so I thought, why stretch it out to make it an hour and a half? But funnily enough, I was at Sundance that year with the short and in the film I cast a real New York City police officer who is a friend of mine, we grew up together. So he came to Sundance with me, we were lodging together and we started talking about the Eric Garner case in Staten Island, where we are both from. One thing led to another and what started out as a regular conversation between two friends ended in a really heated debate. We just saw two totally different things when looking at the exact same video. I’m looking at this video and I’m like, “how could you see anything else other than a person that should be alive? It just doesn’t make any sense to me”. And he said, “Ray, he was resisting arrest”. And I was like, “was he really resisting? It didn’t really seem like he was doing anything crazy”. It was just a different perspective. It was that conversation that ended up becoming the dinner scene in the film, which led to a way for me to take my nine-minute short and make a feature. And this idea of perspective was that way. So the triptych structure was really born out of that conversation I had with my friend.

The short film kind of became the basis of the Zyrick character, so I already had an idea of what that section could be. I thought, this is a way that it might add to this conversation about police brutality, maybe this is a new way, a way that I hadn’t particularly seen done before. It didn’t come immediately; it was six months after Sundance that year, 2015, that I decided to sit down and start writing a script, which would become the film that you’ve seen. So it was a little bit of a journey from short to feature and figuring out what I wanted to do for my first film, the things that were important to me, how to make a film that spoke to personal issues in my life – there are a lot of personal anecdotes in the film. My father worked for the Department of Investigation in New York; he had a gun, he had a shield. I grew up in Staten Island; I had a lot of cops, a lot of firemen, who were my friends, people that I admire for the work that they do, but I have some disdain for some of the practices. So, how is it these people are my friends while there’s a bigger problem going on? What’s going on here? It’s a very personal film in that way. I felt like it was something that was achievable. It was ambitious but it was something I felt like, why not? You only live once, you’ve gotta take a risk. Take some risks and tell something that could add to the conversation, something that could move the needle forward.

And I understand you actually had the title before the story itself. What did “Monsters and Men” mean for you and what did you want it to convey as the title?

Yeah, I did have the title first. It was interesting, a lot of people asked me, “so the cops are the monsters, right?”. I’d be like, “no, listen, I think we all are monsters”. I think that’s what folks wanna hear, it is a provocative title. It’s about the duality of men and women. It’s about the fact we all have good and bad in us, we all have two sides. We have the ability to do something, participate in this process, in this conversation. Or do nothing. And to be honest, with myself, I was like, what am I doing in that conversation? I’m like everybody else. I’m watching the news, I’m seeing really terrible things. And then I go back to eating my spaghetti, or whatever I was doing, watching sports. And is that enough? For me to just be aware? Maybe it is, maybe it is enough. A lot of folks don’t let these issues really affect them on a personal level, thinking, you know, “what can I do? Someone else will handle that issue”, but I feel it’s like that until it happens in your backyard – that’s when folks really start paying attention. I wanted the film to feel like this could happen in your backyard, anywhere. You don’t have to wait for it to happen. These people are your brothers, this is your community, you’re living in a neighbourhood, you need to be aware of these things that are happening, and then moving beyond that to say: what steps can we take as individuals? I was asking that question to myself, am I doing enough? I’m not out there on the front lines where the pickets are. I’m not doing that. I don’t really have a Twitter following – actually I don’t even have Twitter anymore! So what am I doing? How do I engage? I think it depends on the individual, you have to use whatever platform you have. If you don’t have a platform, there are ways to engage, there are ways to talk about these things and not be afraid of it. I think fear puts people off, like, “oh, if I go to a protest I’m going to be injured or be arrested, so I’m not going to participate that way”. “If I say something too political I’m going to get in trouble that way.” So there’s silence – we are often silenced in our viewpoints because someone’s going to attack us. I feel like I wanted to come out of my own shell in that way. Let’s not be afraid to talk about issues that are important and need to be discussed. Maybe I’m getting older and a little bit bolder in my old age to say, “hey, we really need to talk about these things”.

That seems to hit upon the key question posed by the film: is inaction complicity? Where along that spectrum do we all sit? In a sense each of the characters is having to weigh up whether they should take a form of action against the threat of losing their job, their freedom, or future prospects.

Yeah, absolutely, that was the central question – what do you do? That’s a common theme in the film. That was the question that my police officer friend asked me: “Ray, what would you do if you were in that situation?”. Well I wouldn’t have killed him. And he said, “well, what would you have done?”. It’s being able to answer that question for yourself. For everybody, it’s different. I wanted to try and simplify it for the individual. It’s a personal choice how you get involved. You shouldn’t feel pressured to get involved because people tell you to. That was the thing, each character in the film is presented with that: what would you do? What would do when your back is against the wall? Manny, who has already got a pretty dark history and past, is trying to do the right thing. As soon as someone in his community is called out, he’s the first one to jump and say: “Something is not right. My brother, someone that I know, is being wronged. I’m the first one to protect that person.” In his willingness to do that he’s almost sacrificing himself in the process – he’s exposing himself. So those are choices, those are individual choices you make. And I’m not saying that’s what everyone should do but that’s a choice he could make and that’s the way the film presents it. It’s difficult, it’s not easy. I’m not saying it’s an easy thing. I think if you sign up to be a police officer it’s because you want to do the right thing. But if the institution is broken, what do you do? If the practices are wrong, how do you make a difference? How do you make a difference in a place that could potentially be broken?

In that sense, would you also note a difference between the UK and the US? While undoubtedly there are plenty of flaws in our system and racism certainly still exists, watching films such as these suggest the problem is perhaps more extreme or entrenched in the US. It seems as if it could be a losing battle to go up against the US police and justice system.

Yeah, it’s crazy. Yesterday I saw a black dude in the UK talking back to a police officer. I didn’t hear exactly what he said but I just overheard him kind of raising his voice and walking away from the cop. I had just never seen that before. In the States that would just never happen. You can talk back? It was really interesting to see. I was like, oh my God this is a situation that in the States could end in someone definitely being arrested but could even potentially end in someone’s life being taken. And it was such a difference. It was obvious the police officer was not going to chase him but was just one of those situations where he’d pissed him off. But it wasn’t enough to say, “hey he’s a little angry, now I’m going to arrest him, I’m going to put him away”. I mean, I was coming into a conversation that started before I was there – but it was interesting to see that. Because there is a difference. Obviously, also there are way more guns in the States than typically here in the UK.

While racism and police brutality have long been issues, it seems like only now are they really coming into the public consciousness and being exposed through the media and film, thinking of The Hate U Give, Detroit, If Beale Street Could Talk etc. What do you think the role of cinema is and what do you hope this film will achieve in terms of raising awareness, adding to the conversation and potentially prompting change?

I think the more the merrier. The more we have films that tackle certain issues, great. So long, as you said, it’s adding to that conversation. People are coming at it from various different ways. If I were a comedian… I wish there was a way to tackle it in a funny way – let’s have a laugh about it. Films can make a difference. I think that’s how films should be. There are so many different ways to engage with [the issue], this was my way. I’d taken a sort of a serious tone with the film; it was something that I felt worked in my short, I had a visual language for it and I just expanded that same tone that worked in the short because people seemed to respond to it.

Again the triptych structure was something that I hadn’t particularly seen with the subject matter. These seem interesting; it’s offering perspective, it’s not something that I feel like you’ve seen before. So I felt that there were a couple of things that we did to try to make it interesting for folks to engage with. Yeah, the more the merrier, the more films that we have to talk about these issues the better. It’s weird, I didn’t necessarily set out to make an issue movie, I set out to make a movie. These are issues to other people but this is how my community is, this is the way I was raised. It’s like, I’m telling my own personal stories and they become issue-based films. It’s interesting from that perspective: if there’re black people, if there’s crime, it’s an issue movie. It’s just how sometimes they’re presented. I’m not saying they’re not tackling something at the heart of them. But it’s not what I set out to make. I didn’t want the film to feel didactic, I didn’t want it to feel preachy. We tried to remain objective in how we shot the film and how we communicated it. So, in that respect, I tried to take out a lot of that stuff – just have your audience feel complicit in the process. Is there a takeaway? Yeah, I hope so. I think it’s different for each person – and maybe you’ll tell me what you took from [the movie] – but I hope it inspires folk to go and do something, however small.

For me, there’s something about a film that can foster empathy in a powerful way by putting you in the shoes of a character. In this case, the three narratives don’t necessarily tie together but in each section you’re plunged into that person’s part of the story, weighing up all the different pressures on decisions they make. I find it really refreshing as it’s not telling you what to think but trying to make you question whether you would make those decisions in those circumstances yourself.

Well I hope there are some connections in the film. It doesn’t come back in the way Crash brings back characters. It doesn’t do that because, first of all, Crash was made and I didn’t want to remake it. I wanted to make something different. But, for example, we set the neighbourhood as a character in the film. In the same way Spike Lee uses Sal’s pizzeria [in Do the Right Thing], we use the deli. We come back to that, all of our characters come back to the deli in the film. So location is a character. We try to use connectivity in that sense. Also, Manny maybe doesn’t come back in the film but his name lives on. Each character is a mirror reflection of themselves. John David’s character looks at Anthony Ramos’s character in the mirror and he’s looking at himself. And the flip side of that, when he’s looking at Zyrick, he’s looking at himself. So there are a lot of mirror images in the film and I feel like that was our way to connect the community. Yes, we can be completely different people on completely different sides but we’re all human, we all have the ability to not pass each other in the street. We arc over each other, we can all empathise with that; you can put yourself in someone else’s shoes, we all have the ability to do that. So hopefully those connections live on. The final image of the film, “I am Darius Larson”, that goes for every individual in the film, us as the audience members – we feel we are Darius Larson. The name lives on. Hopefully we are connected that way.

And coming to the cast, you’ve got John David Washington, Denzel’s son, who is phenomenal as the police officer, plus two other fantastic actors in your two other main roles. Did you have any of these actors in mind when writing? What was your casting process?

When I first wrote the roles I didn’t have a particular actor in mind. I knew I was gonna need young kids: Kelvin’s character is young, Anthony’s character is super young. I thought the police officer role lent itself to a name in terms of where it sat in the film, you know, because of the Prologue, because it’s the central character, because it’s connected on both sides in a way that some of the other characters are not. That sort of lends itself to a name. I think all three of them somehow all started on Skype. Spike Lee was the one that told me about John David. I went to Spike for office hours at NYU and he was like, “I got it, John David Washington” and I was like, “who’s that?”. And he was like, “Ballers? You don’t watch Ballers?”. Then I realised who it was but I hadn’t recognised him, he had long hair and an earring. He needed to play a New York City police officer – could he do that? So we Skyped and I met him and then he came to the Sundance lab with me. We spent three weeks together and I fell in love with him. He’s really incredible, he showed me something that I hadn’t seen. The role really needed to be played by somebody who could tap into that empathy and you really like John David. He’s got those qualities and he’s a brilliant actor. So that’s how that came about. Anthony Ramos I cast off of Skype. Literally, I mean, I think I gave the role away mid-sentence. I was like, “did I just…?”. I didn’t even check with producers, I just accidentally gave him the role. I just felt like it was tailor-made for him. And Kelvin Harris was probably the funniest story because I saw him in a movie that wasn’t yet released. I went into the edit room with another director who invited me in graciously, [saying] take a look at this kid. So I looked at him and thought he was amazing. But he had no athletic ability whatsoever and he needed to be an athlete in the film – he needed to be almost a pro athlete. I didn’t know that he couldn’t play sport at the time that I cast him – he [couldn’t] even dribble a basketball…nothing, like, really unathletic. But he’s such a brilliant actor, he’s got such a great face. His is the character that says the least with words and I needed someone who could really communicate what was going on in his head. Kelvin really captures that. So the sports was only “this” much, we just need to sell the fact that he was an athlete. He gained 30 pounds for the film, of muscle. He was like, “I can eat”, and I was like, “well just eat, just look good”. He had the abs and he looked good, he’s a really good looking guy. So, we sell it. We have a whole bunch of body doubles that do his little sports routine. But he really got into the headspace of an athlete through hanging out with professionals as part of the character research that goes into the film.

Speaking of Spike Lee, what was like being taught by him at NYU?

Well, obviously, he is an icon so in his classes he brings a lot of guest speakers, people that have worked on his films. Spike is a man of very few words, he is someone who wants you to go out and get it like he went out to get his own. He is not one to do favours, he’s gonna tell you the truth about how he feels. But he’s also someone that has watched every single short film I’ve made. I made seven short films at film school, and he’s watched them multiple times. And I know he’s done that for every student over the course of however many years. So he is a genius and he is someone that is a pure lover of cinema, he knows almost every film that was ever made and he watches them. He’s someone who puts in the work. He gets up every day at 5:30am or whatever, he has a routine. I would ask him all these questions, like, “Spike, how do you write your scripts?”, and he showed me how he puts it on index cards and then transfers it from index cards to a notepad. And then he’s got all these pictures and it’s all written in “Spike language”. Spike’s penmanship was really interesting, really special. So he’s an incredible guy. You learn from watching a master more than a teacher in that respect. He’s more like a mentor, that’s how I view Spike, as a mentor to his students more than a teacher. He teaches you by saying, “look at the work, that’s how you do it. Go out and get it”.

Can you briefly tell me about the boxing film you’re working on about Jack Johnson?

We’re in the rewrite process of the Jack Johnson film, something Ridley Scott and his wife are producing. It was an incredible opportunity to tell the life of a man that has been kind of forgotten about. He was Ali before Ali. It’s a period piece, it’s really special. So I’m excited to get to that as soon as the writing’s done and start moving into the next chapter.

And you’re here in London filming the third season of Top Boy at the moment, right?

Yeah, I filmed it already. My edit’s done, now I’m waiting for the rest of the series to complete itself. I’m excited. Top Boy was obviously just an amazing opportunity to come here to London, to work in the UK with such incredible actors on an incredible show. I think Top Boy is a really special show. I was a fan before ever coming to it, so it was really amazing to get the call to do the job and bring it back. Drake is involved in the show as an executive producer and obviously is involved in Monsters and Men so there was some crossover there. I think people are going to be really surprised and excited for the new season. I’m just delighted to be a part of it.

Well at least it wasn’t too cold during your stay here in London!

Yes exactly, I’m in a T-shirt and leather. I’m very lucky. I’m going back to New York tomorrow, so not looking forward to the brutal weather there…

Hopefully it’s not too brutal! Thanks so much for your time and congratulations once again on the film.

Sarah Bradbury

Monsters and Men is in released nationwide on 18th January 2019. Read our review here.

Watch the trailer for Monsters and Men here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS