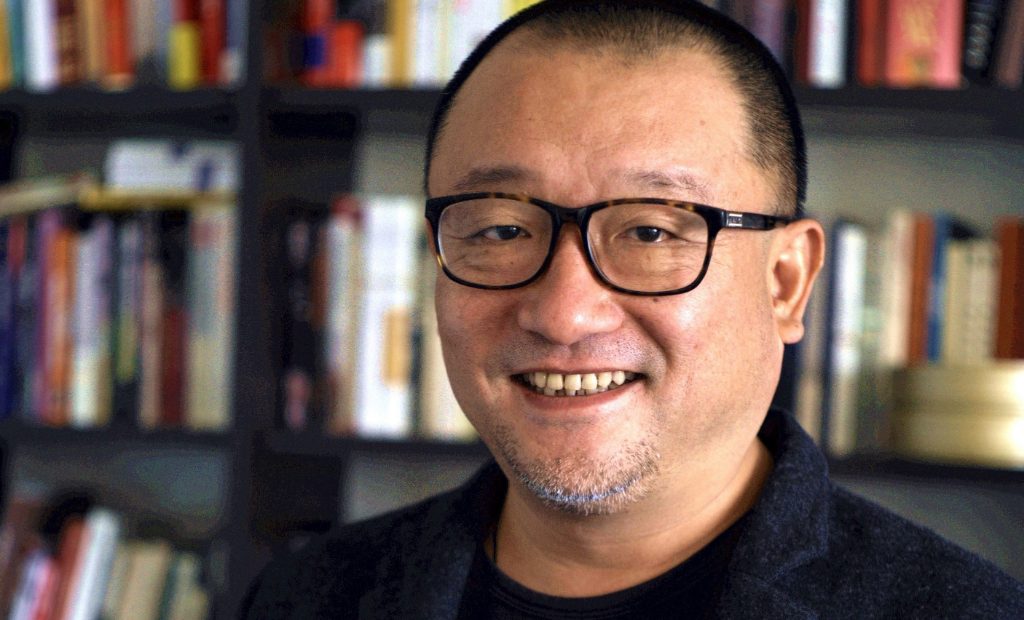

“As a director, I feel that there’s a dance where you examine social changes, and how you are to an extent sceptical or critical – that’s part of your fundamental mission”: An interview with So Long, My Son director Wang Xiaoshuai

When sitting inside a cinema and watching a film, the very passage of time can be forgotten, or perhaps amplified. The movie unspools to a running time that the filmmaker feels was necessary to tell the story, whether it’s a brisk 85 minutes or 485 minutes, as was the case for director Lav Diaz with his 2016 Berlinale entrant A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis). Whether or not the audience truly notices the time that passes as they watch the film depends entirely on the film in question. Director Wang Xiaoshuai’s So Long, My Son clocks in at three hours, and yet feels singularly succinct. Encompassing three decades in the life of a Chinese couple, the feature uses its characters to comment upon China as a whole, and the notion of time becomes brilliantly knotty, delving back and forth between different periods in a way that wrongfoots the viewer in a refreshing manner. We spoke with Wang Xiaoshuai shortly after the world premiere of So Long, My Son.

The film plays with the concept of time, jumping back and forth between different periods in the characters’ lives. It must have been a complex undertaking, and so were you ever to tempted just let the story be told in a straightforward chronological order?

I started trying to do it in a linear chronology, and in fact the first version of the screenplay was prepared accordingly. I asked my screenwriter to put all these major plot elements in, and then we tried to do that, but it wasn’t possible. If you want to do it as a strictly linear progression, there are so many different eras that you have to define, and all of these huge changes that happened in China, which you also have to define. It becomes impossible, it becomes like building an entire city. Then I re-adapted the screenplay in a different way, and I wanted to do it so that all of these changes that happened within three decades or so form a story that can work like a day’s worth of storytelling. So I took what was probably quite a risk in the end. I deliberately didn’t label which year or which era the various events were taking place in the film. I didn’t want people to be deliberately following different dates or different timelines. I wanted them to just be following the story of the people.

The film is not necessarily political, but there is some unavoidable political commentary in the story. Were you ever worried that these observations and critiques would be too harsh, perhaps even angering the Chinese censors?

That point has always been a challenge for Chinese directors, but for me, the most important thing is no matter what environment I’m in, what the government is doing, what is being done in regulatory terms, the key question for me is really whether I have a good story and if I have something that really resonates. And it’s very important for me to avoid creating a form of self-censorship. If we take this bottle of water on the table in front of me, and it has to go through censorship, that censorship has to be the last stage, after I’ve thought about whether or not to make it, and after I’ve thought about how to make it, and finally when it’s there on the table it can go through that censorship process. If I allow myself to think about that when it’s an idea that is still inside me, and whether it will work in censorship terms, that is too much of an impediment. As an artist, as a director, I feel that there’s a dance where you examine social changes, and how you are to an extent sceptical or critical – that’s part of your fundamental mission. Because the individual is in a very weak position vis-à-vis the whole of society, and perhaps it’s only art that can help somewhat to redress that balance. China is a very particular environment to work in, and what I generally try to do is to look at the experiences, the concerns of ordinary people as my starting point. If I was an American artist, I’m sure that I would be critical of the American government, because it’s only with a degree of scepticism and criticism that you can reach progress.

While Chinese filmmakers have to work with official government censors, do you, as a filmmaker who comes to international festivals and speaks with international journalists, ever get sick of having to explain and even justify this aspect of a system you have no control over?

I do find some difficulties with it, and it does tire me out sometimes, because a lot of Chinese issues, also political issues, are simply not things that you can easily summarise in one or two sentences. When people are trying to get something done in China, they often won’t bring up the point right away, and they’ll say all this other stuff first, and make you gradually understand what they’re trying to get at, and it is very difficult to deal with. There’s a particular group of people in China from three northeastern provinces, and we just refer to them as northeastern – these three particular regions of China – and they have this hallmark that whatever they do, they try and do it through personal connections. They go out to a restaurant, and they don’t just walk into a restaurant and order something. No, they find some friend of theirs that has a personal connection with the boss of such and such restaurant, and they do everything the same way whether it’s finding schooling and education, or work. It’s very complicated.

Oliver Johnston

Photo: Xu Shengzhi

So Long, My Son ((Di jiu tian chang) does not have a UK release date yet. Read our review here.

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS