“I’m only brave because I’m incredibly fearful”: Charlotte Rampling on receiving the Honorary Golden Bear for Lifetime Achievement at the 69th Berlin Film Festival

British actress Charlotte Rampling, now 73, started out her career as a model but quickly made her mark in the film industry as a gutsy and non-conventional arthouse actress, taking on taboo-busting roles from Georgy Girl (1966) with Lynn Redgrave, to Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (1969) to perhaps her best-known role in Liliana Cavani’s subversive and controversial The Night Porter (1974) as a Holocaust survivor.

Other films included Farewell, My Lovely (1975), Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories (1980), The Verdict (1982) with Paul Newman, Angel Heart (1987) with Mickey Rourke and Robert De Niro, a number of films with French director François Ozon, namely Under the Sand (2000), Swimming Pool (2003), Angel (2007). More recently came The Duchess (2008) with Keira Knightly and Andrew Haigh’s 45 Years (2015) with Tom Courtenay, about a married couple celebrating their 45th wedding anniversary, for which she was awarded a Silver Bear for Best Actress at the Berlin Festival. TV appearances have also included Dexter, Restless, Broadchurch and London Spy.

This year, at the 69th Berlin Film Festival, the renowned actress was presented with the Honorary Golden Bear Award for Lifetime Achievement in film, in the last year that Dieter Kosslick, who is a close associate of the actress, will be the Berlinale director. He called Rampling “an icon of unconventional and exciting cinema”. A selection of her films were also screened during the festival.

We had the honour of sitting down with Rampling ahead of the award ceremony to hear her thoughts on her career highlights and challenges, how she sees the process of acting as a reflection of the self and her views on women’s place in the industry today.

Hi Charlotte, such as pleasure to meet you. First of all congratulations on this incredible lifetime achievement award. Can you start by telling us what you think makes the Berlin Film Festival special for you?

It’s certainly one of the biggest, alongside Venice and Cannes. But this one I can say perhaps I have more of a connection with. I have a relationship with Germany, that’s for sure. I’ve worked with a lot of German artists, not so many German directors of films though. One, Angelina Maccarone, we did my autobiography. I worked with quite a lot of German photographers, three very famous photographers over the years. So there’s definitely something there because when I think about Italy then I think about Germany, there is something more going on there that actually works for me. It’s like a calling that you have of places that somehow speak your language, not literally, as I don’t speak German, but an inner language.

And what does it mean to you get this Golden Bear on Dieter Kosslick’s last Berlinale?

Well, actually, he asked me last year and I couldn’t do it as I was filming at that time. I didn’t quite know when he was going then, he didn’t say. But then he caught up with me at the end of the year and said, you know, “it’s my last” and he said, “you did promise”. So it’s actually very beautiful somehow because I have a very strong relationship with Dieter Kosslick.

Did this award provide an opportunity to look back on your career? Did it prompt you to think about what you mean to people and what speaks to people in your work?

Yeah, you can only know that by what they actually say to you over the years, how they’ve supported you, or not, over the years. How they’ve come in, and come out. Because the people are actually your gauge of who you are in a sense as an artist, not who you are to them. You can be going on your way and actually not really connect with the people, your audiences, let’s say. In my case, what it seems to be is that people have very much connected with the person via the roles. So what they’ve perceived is what actually I’ve given them. I never really wanted to be an actor in the sense of the brilliant actors that I see doing all sorts of different things, I wanted to actually interpret and be and live through another character. It’s always going to be me. So the authenticity of my humanity is always going to be. I’m not going to actually harm that.

Was there something special you were looking for in your career?

No I’ve never thought about looking for something because I don’t think that way we ever find it. But along the way, I’d like to be able to, you know, have a little sort of glimpse maybe: “Oh, perhaps it’s there”. And then you go on to another thing.

They are showing The Night Porter here at the festival. What are your memories making the film and working with Dirk Bogarde?

Well, it was a film that was very unusual at that time, even though it was the beginning of the 70s so these types of films were beginning to emerge, films that were telling us about our history and telling us about our taboos and opening doors into different understandings of history and life. And this was certainly one of them. I did it because I’d just done the film with Visconti, The Damned, where I met Dirk Bogarde and it was Dirk Bogarde who had The Night Porter. So I did it because of Dirk.

Would you say François Ozon made some kind of second discovery in your career with films such as Under the Sand and, of course, Swimming Pool?

In a way The Night Porter was very much the springboard that then led to Ozon. Doing The Night Porter with Dirk on a subject like that made everybody either hate it, love it, whatever. But it existed. I was the “kinky queen”. I was whatever I was, I was out there in cinema. And the film subsequently became what it became. All those years later, because I was in my early 50s when I did this film, Sous le Sable, I was wondering whether I even wanted to continue on in films at that time. I almost wanted to kill off the beast and just see if anything could grow out. Ozon appeared and was able to do that, which then sort of took me on a journey. You need these key things I think in a lifetime of film, you need key moments that actually other films hook onto that aren’t so, perhaps, commercial, aren’t quite so powerful. They define your career actually. They define who you are in a way.

What was the initial key moment in your career do you think?

The very first one would be Georgy Girl, I don’t know if you know that film, an English film, but it was a huge success at the time where I played an outrageous character in the swinging 60s with Alan Bates and Lynn Redgrave. That was the first one, that was when people went, “oh, what is going on here?”. People said “you’ll never get another role, you’re so awful, so horrible in this film”. Because you had to be quite nice to be accepted.

In fact, you did that many more times in your career?

Yeah, yeah. I’m not here to be liked!

But you are.

But I am. [she replies with a smile]

Did being the “kinky queen” influence all the films that came after then?

Of course. Because when you have a very strong film it absolutely influences everything. They’ll send you all sorts of weird kinky things or whatever. But I remember with Georgy Girl thinking, “she’s so independent, she’s so does everything according to her rules she fucks everybody off”. People said, “but she’s gotta be like that, she must be the most awful woman” talking about me because I was so convincing in it. So people actually really do believe that. But it’s good. I mean, I wasn’t frightened of that. Obviously not, otherwise I wouldn’t actually be here today.

Such taboo-breaking roles have brought acclaim but also have resulted in a backlash at some moments, thinking of The Night Porter and critics such as Pauline Kael, for example. How did that effect you? And do you think the nature of criticism has changed over time? Now with social media, everything is so much more immediate.

I don’t think it’s changed but it’s just as you say, with social media, they can immediately throw shit on you, right? Before you had to sort of wait until the papers came out. Now everybody can have a handle on it. Everybody has a voice now so we can say, “isn’t this wonderful, isn’t it democracy that we absolutely have made, oh woohoo everybody has a voice!”.

So would you say you were brave?

I was truthful. And I wasn’t frightened of my truth. Because that’s what I had to live with. So if they didn’t want it then I’ll have to get on with it but it’s mine, I respect that. I didn’t want to pander to anybody and I never have. Certainly not in work. Maybe I have been in my relationships but we’re not talking about that…

What do awards mean to you, especially Lifetime Achievement Awards?

Lifetime achievements I don’t like. But Berlin yes. In festivals, they want to always give you that when you get to a certain age because they want you at their festivals. That I don’t like that. So I say no to all those. But this one obviously I said yes to because there’s something very beautiful about getting a Lifetime Achievement Award in Berlin with Dieter Kosslick as his last sort of thing. No problem there. I’m very, very pleased. And also my Silver Bear was saying, “can we one day have a Golden Bear?”. And he’s got it! Now they’ll be nose to nose.

How do you choose your roles today?

My feeling is that, well, there’s a lot that doesn’t suit and then suddenly one sort of suits, one is the one. There’s no method, it can be, you know, a first-time director, young, inexperienced and it can be a Paul Verhoeven, you know, 80 years old, I just filmed Benedetta with him. It can be anywhere and anything but I have to feel that that’s what I want to do next.

Are there any directors you would go immediately with before even reading the script?

Would I? Yes, maybe there’s one or two directors I would do that, yeah.

Has it become harder to be truthful, to be rebellious in a way nowadays than it was earlier?

No, it’s becoming easier. It becomes easier and easier I think actually. Maybe until we just fall off our perch. Because you actually free up getting older. I think everyone will tell you this – you’re probably not old enough to know it – but it’s actually a very good experience because you become freer and freer. You just sort of know more and more without any probability or doubt. “Now that’s what I want to do. That. Not that. That”. Whereas before I would think, “oh, maybe, I need to discuss it”, and I wasn’t sure. Not anymore. It’s quite remarkable now.

So age brings a lot of self-confidence in this case?

Yeah, I suppose. Because it’s like, if you’ve really worked on yourself, which in my profession you sort of have to, you’ve been brought to really considering so many aspects of yourself and your inner life and your outer life and all that. You’ve done that journey, you’ve actually come to some sort of understanding, subconsciously. It’s not a conscious thing. So that then you’re apt to make a decision, it’s, “oh, yeah, that’s the one”. Before, I really had difficulty deciding. Not because I didn’t want to do things but because there were lots of other things that you had to consider. Somehow all those other things you have to consider are not there anymore. I don’t quite know where they are. Perhaps it’s the family, the children, the this, the that, responsibilities, you’re sort of looking out for others – I don’t know what it is. But I know it’s not just me. A lot of people say that, people of my age are saying: “It’s much much easier now!”. We should promote it because people get so scared of it.

Does that have an effect on your acting skills as well, when you’re in front of the camera, to have this greater sense of security?

No, it hasn’t yet. That’s something else.

Perhaps insecurity in front of the camera is actually important to getting it right?

I think it is. Because I think that whole domain of insecurity, let’s call it, has to be there because you are going into new territory. It’s not like a theatre production that you’ll rehearse and rehearse until you feel it more and then you’re onstage and you finally perform, but film, each time it’s new, each scene is new, each moment is new, each thing that happens to us is new, it’s [gasps] coming at you.

The good thing about film is once it’s done, it’s done. You have it in the can. Theatre you have to renew it every day.

Yeah but that’s great too. It’s another method that also is very interesting.

Did bringing in your persona to your roles to your art ever make you vulnerable as a person?

Well obviously all actors will bring in parts of who they are. It didn’t make me vulnerable. On the contrary actually. Why I did it unconsciously also perhaps is because I wanted to share. I’m only brave because I’m incredibly fearful. But not fearful about what’s happening in the world, I’m fearful about what happens inside myself, my work, who I am inside myself and my reactions. So actually I like that, to have a character. For me acting with a character is wonderful because I have an accomplice. So you’re not actually having to sort of face it all necessarily on your own. So that worked very well. Probably one of the reasons why it actually worked very well. It was great not to have to do all that stuff in real life!

Looking back, is there anything that you’d say you would regret or you found particularly challenging?

I find everything very challenging. Don’t you find things challenging? I’m just a human. Everything is incredibly challenging, fearful-making and all that. Living life is dominating your fear. But if we don’t have fear we don’t do anything because fear is an incredible motor, it’s fabulous. But if it dominates you, then you close down. I keep throwing myself out into the world so that I’m constantly challenging that, I’m constantly challenging the devilry inside me. Saying, “OK we’re going to go out there and we’re gonna do it”. And we do it together.

You mention the key films and key points in your career. Did you watch all your films and pick out the ones showing here in Berlin now?

I mean, I have done a lot of films, like people say, “oh my gosh, she’s done 100 and something films”. They’ve got bits and pieces of interest. There are all types of film. But the ones screening are the films that seemed to shine out in terms of the person and the personality and the actor that I am best. Because I see my career as kind of a marginal thing. Do you know what I mean by that word? Maybe I’m thinking of it in French marginal but I’m not quite sure it works in English… It’s like a career that’s gone alongside me. I haven’t gone way out. I didn’t want to go to Hollywood because it was not my world, all these films had to correspond with my path, my journey, who I am, in a sense, had to correspond to my life. And these are the ones that I think emerge most to illustrate that.

When you received offers from Hollywood, what were they?

It was in the 70s that I actually did one or two films in Hollywood. They were sort of uninteresting films, no big, big films. If you were to get big films, you would need to go to Los Angeles and live there, get an agent there and work there and do the castings. You have to go into a process with Hollywood, you can’t arrive there and say, “look, I’m Charlotte Rampling, I made a few films in Europe”, you know, no way. A lot of Brits went out there, some managed to work the system and do work and others just came home. Because it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work like that. I mainly got New York-based films, the Woody Allen films, and I think Farewell, My Lovely was my last one in Los Angeles. I did Orca the killer whale before that. Dexter was also Los Angeles. I did films to see what it was like, to see whether I liked the big types of films and see whether they could be part of my life. But it wasn’t my style.

Totally different question, what do you think about Brexit?

Well, I won’t comment on it. But I just hope that it is something that is is going to be a construct and not a deconstruct. It’s such a big thing.

Can I ask how you see the conditions for women in the industry? You’ve been in the industry a long time – how have you seen it change and with movements like #MeToo do you think that we’re making positive steps forward?

I can’t say because I’m not in it. I’m an actor, so I’m always treated well. People haven’t hassled me, I haven’t had those problems, so I can’t say. I can’t unless I’m on the terrain and know what’s going on with people. So they’re much better talking about it than I.

But might you say there are more character opportunities? There’s more diversity of roles there for women than perhaps there were in the past?

I’m sure it’s going to help, you know, absolutely. But I mean, when you think of the cinema of the 40s and 50s there’s been some fantastic women’s roles. So I don’t know what everyone’s talking about. But what they’re talking about in terms of the #MeToo movement and all that, they are absolutely justified and so they must do what they feel is correct.

Thank you very much for your time and congratulations on this wonderful award.

Thank you.

Sarah Bradbury

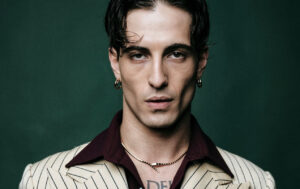

Photo: Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS