Dorothea Tanning at Tate Modern

When the American artist and writer Dorothea Tanning died at the age of 101 in 2012, her passing was widely described as the last gasp of Surrealism. Despite a career spanning a remarkable seven decades, she has been largely overshadowed in terms of fame by her male contemporaries. For many, the artist is better known as the wife of the German Surrealist, Max Ernst. In recent years, Tanning’s work has been enjoying something of a reappraisal. In 1997, the Tate Gallery acquired one of her best-known pieces, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943). The present, arguably long-overdue retrospective of the artist’s oeuvre at the Tate Modern promises to – in the words of the exhibition’s co-curator Alyce Mahon – readdress “the old idea of Surrealism just being about the objectification of women”.

Tanning was born in an archetypal small American town of Galesberg in Illinois. She would memorably later remark that, “nothing happened but the wallpaper”. The young Dorothea broke the humdrum tedium of her existence there by reading Gothic novels and poetry. That Gothic literature influence was particularly marked in the surreal imagery of her early pieces, which also bore witness to her familiarity with Freud’s ideas on the subconscious mind.

The Tate has gathered together in excess of 100 works ranging from the artist’s commercial illustrations of the 1930s to the final paintings of the late 90s. Among the early works featured is her celebrated self-portrait Birthday (1942). This powerful painting, demonstrating Tanning’s flair for meticulous detail, was the work that first brought her to the attention of Max Ernst. She stares confidently out from the canvas, bare breasted and bare footed, beauty in evidence, her fantastical skirt partly made up of tiny, interconnected figures whose limbs resemble roots or branches. In front of her sits a Chimera, a mythical winged hybrid creature. She opens a door onto a corridor of open doors. For Tanning, doors came to symbolise the portal to the unconscious, to our secret fears and desires. When Max Ernst was introduced to her in her studio, he was searching for 31 female artists to take part in an exhibition at the gallery of his then wife, Peggy Guggenheim. Ernst actually suggested the painting’s title, intending it to signify her birth into the world of surrealism. The two artists would quickly fall in love, apparently over games of chess and eventually marry in 1946 when they moved to Sedona, Arizona.

It was the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism of 1936 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that first drew her to surrealism. Tanning spoke of how it taught her of “the limitless expanse of possibility”. Throughout the following decade, domesticity was a prevailing theme in her work. The afore-mentioned Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943), featured in this exhibition, has at its core notions of suppressed desires and budding sexuality. Two young girls in a hotel corridor by night are engaged in some terrifying battle with an enormous sunflower blocking their path to the stairs and an ajar bedroom door emitting light.

This Tate retrospective, the biggest show of Tanning for 25 years, reveals her career to have developed away from meticulously rendered figurative dreamscapes. By around 1955 she can be seen deploying more gesture and movement to her brushstrokes, opting for a semi-abstract approach. From the 1960s, in the large-scale work such as Dogs of Cythera (1963) she called her “prismatic paintings”, various bodies merge into each other.

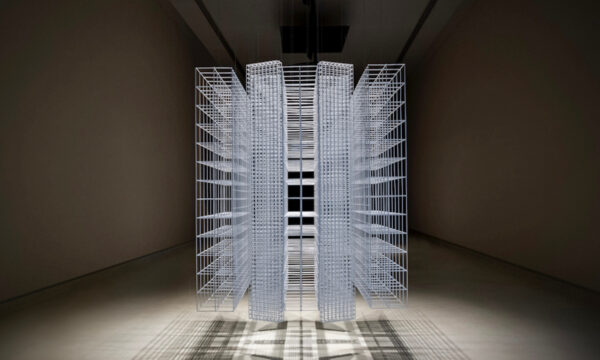

For many, however, the most rewarding part of this show will come in the artist’s soft sculptures dating from the mid-1960s. Expressing her boredom with turpentine, Tanning started producing anthropomorphic forms with her Singer sewing machine, using fabric filled with wool, sawdust and other objects. These instantly recall later work by the likes of Louise Bourgeois and Sarah Lucas. The climax of these sewn sculptures is the alarming whole room installation Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot (1970-3). Bulging stuffed female forms burst through the wallpaper and swamp the furniture of an already disturbing hotel room. It’s full of Gothic horror and yet still humorous and sensuous at the same time. Ultimately, this often surprising, frequently enjoyable show offers a rare opportunity to experience Dorothea Tanning’s unique internal world.

James White

Featured image: Dorothea Tanning, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

1943. Tate. © DACS, 2019

Dorothea Tanning is at Tate Modern from 27th February until 9th June 2019. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS