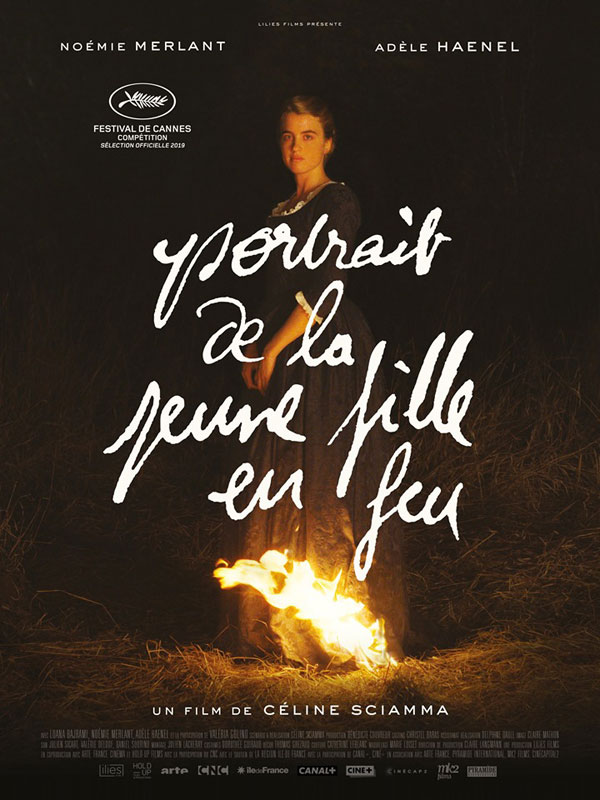

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Portrait de la jeune fille en feu)

This extraordinary film builds upon John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and Walter Benjamin’s theory of art, transforming the male abstract – ideas of gaze and reproduction – into the female concrete. Furniture, clothes, bodies and relationships are deliberate placements, mannered and stylised, the backdrop on which women suffer and prosper in 18th-century France, in a quiet palatial home containing a snare of secrecy, an obstinacy, a difficulty. What a riveting, gorgeous illustration of how the eye works and how it doesn’t, how it at once focuses and distorts perception.

The conventional oil painting is pristine and exact, referential and symbolic. It contends directly with its subject and with itself – as an object within the frame of beauty, art and aesthetics. Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire likewise contends with its subject, painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant), and her subject, aristocratic bride-to-be Héloïse (Adele Haenel), producing a doubling and redoubling of form and composition. Multiple perspectives obey a single authority split into fragments: Sciamma as director; Marianne as artist; Héloïse as sitter, autonomous, elusive, willing to stare back.

This sounds like an exhausting academic exercise but Sciamma renders at its centre a forlorn, bristling romance, one essentially defined by brushstroke and facture. To handle paint is to handle the body. To turn away is to forgo vision, to reject understanding of the interior being. Ways of looking and seeing establish Marianne and Héloïse’s interactions, these purposeful and controlled until accident: a splatter, an omission, a flame that licks the fabric.

The power relations between the four women – Marianne, Héloïse, Sophie the maid (Luàna Bajrami) and the Countess (Valeria Golino) – must be essentially amorphous. Norms and etiquette constitute a shifting plane on which polite expectations wilt under transgressions. Marianne paints as she likes; Héloïse hides her body and resists observation; Sophie eats at the table; the Countess takes an extended absence.

Dorothée Guiraud’s costume design provides the crucial link between material and psychology: the translucent veil that reveals the mouth, the stark greens and reds, the white dress and the black corset. Away from the house, beach and coast act as exceptional spaces that soothe repressions, that allow Marianne and Héloïse to be indulgent, poetic, romantic.

Male influence exists everywhere but any direct imposition – the sight of a man, the visual anticipation of marriage – offers a distinct obscenity, an unaccountable rupture. So painter and sitter must cling to fleeting moments, to discussions of Orpheus and Eurydice, to fitful glances at the piano, to page numbers in a book.

Scenes at an art gallery and opera house exhilarate. These are neither summaries nor appendices but vital components. They present two truths with mitigation: a conventional portrait with a smuggled indiscretion and a conventional life with the memory of escape. What appears to be perfect unity produces anomalies, and in doing so creates a masterpiece.

Joseph Owen

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Portrait de la jeune fille en feu) does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Watch some clips from Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Portrait de la jeune fille en feu) here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS