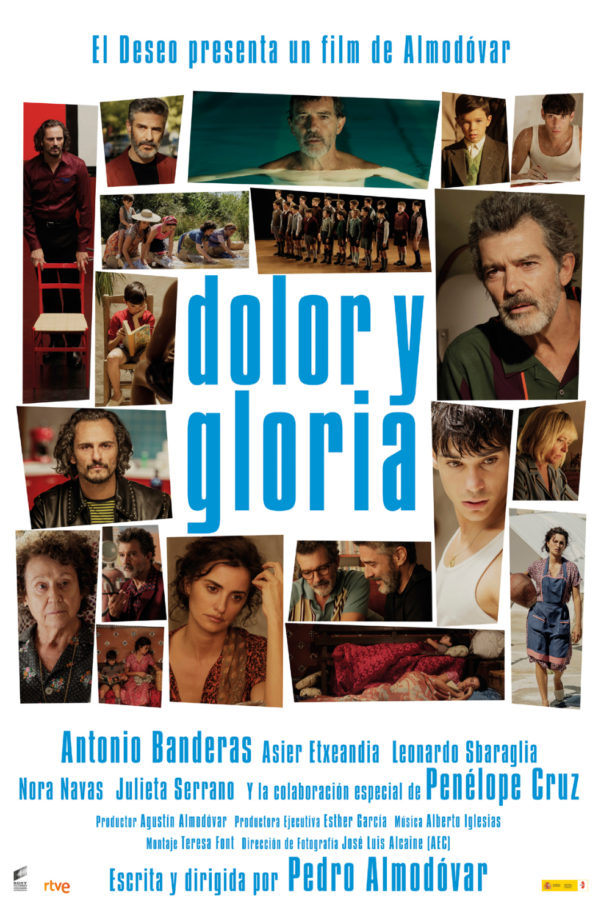

Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria)

There is a grand tradition, late in a director’s career, to make what might be referred to as their 8½. The most obvious example is Fellini’s 1963 opus, but the idea of a director making a veiled autobiography that prominently features their industry – and doubles as an interrogation of their own process – is a common one. (To name a few: All That Jazz, Stardust Memories, Barton Fink, Knight of Cups.) Sometimes the most exciting element of this is trying to work out what’s fictional and what’s real, and whether such a distinction matters in the first place; whether the filmmaker’s wildest flights of fancy are representative of their “real” selves more than anything else.

Pedro Almodovar’s latest, Pain and Glory, is about a director, Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas). He hasn’t made a new film in years, obsesses about his own health, and spends most of his time shuttered away, thinking about his own past. When a prominent cinema puts on a retrospective of his work, he’s prompted to reach out to Alberto (Asier Etxeandia), an actor he hasn’t spoken to in years. The two strike up a bond over a heroin addiction, which Salvador apparently develops out of sheer boredom, and subsequently has trouble managing. Interspersed with this is a depiction of his childhood, with Penélope Cruz playing his mother. Salvador wonders where he went astray in the time in between.

Having first made his name with an excessive, queer sensibility, then fusing that with a more accessible, melodramatic form in the late 90s and 2000s, Almodovar now seems to have tipped over the other way. Pain and Glory certainly doesn’t lack for colour or texture, but it is quite flat. Banderas gives his all in the role, but there’s only so much one can bring themselves to care about a rich, privileged director having a mid-life crisis, and the dramatic stakes are virtually non-existent. What’s left are, like in 8½, interludes about the nature of creativity. Some are lovely; a rekindling encounter with a former lover (Leonardo Sbaraglia), a flashback to Salvador tending to his dying mother (played, as an older woman, by Julieta Serrano). But much of it fails to make an impact, simply bouncing off the maxim that pain is key to creating great art.

And then there’s a final scene so shocking it made this critic gasp aloud. It won’t be spoiled here, but a second viewing is a must, if only to help clarify what’s fictional and what’s real, and whether such a distinction matters in the first place.

Sam Gray

Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria) does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Watch three clips from Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria) here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS