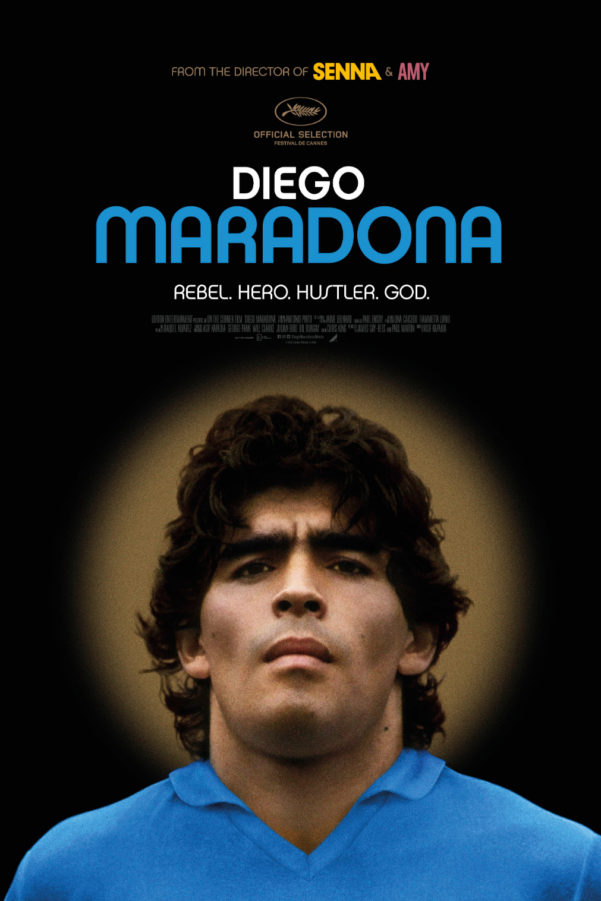

Diego Maradona

Diego Maradona embodies the footballer as double: saint and sinner, hero and villain, God and the unholy. Asif Kapadia’s propulsive documentary teases the possibility of a higher third, a complex of opposites that reconciles the artist as a young man with the degenerating figure of the present. It doesn’t entirely succeed but remains an absorbing portrait, justifying the implication of the title: that there exists the articulate, personable Diego and the exalted, mediatised Maradona.

We focus on the footballer’s time playing for Napoli, the most productive, deliriously consuming years of his career, one in which he both won and reached the final of the World Cup with Argentina. We have a familiar trajectory: precocious ability, mounting acclaim, accompanying pressures. Kapadia wisely elides his subject’s early years into a bracing montage, soundtracked by Todd Terje’s Delorean Dynamite. We see him home at Boca Juniors, the unsuccessful sojourn in Barcelona and the transfer into Serie A, what was then the best league in the world.

Kapadia resorts to similar techniques found in his works Senna and Amy. Disembodied voices are laid over archive footage while ominous images linger: Maradona in his prime, feinting, turning one way and the other, hacked to pieces; Maradona at the team Christmas meal, isolated, staring elsewhere. Pitch-side sequences forge a dread-filled form of anticipation: that his future is not a place, and not much of a time. The physical and social violence imparted on him is impressed upon us. Talent is seen as ephemeral, at first intoxicating and later imprisoning, an iron cage that neither relents nor emancipates.

Being in the public eye is viewed as inextricable to his downfall. Maradona conducts mock interviews to satirise perceived press agendas. The upset of addiction, his links with the Neapolitan mob, his promiscuities: all are centred and decentred, interspersed with his exquisite dribbling, passing, shooting, competitiveness. There’s a reason why the outstanding, unreliable genius in a team is known as mal leche, bad milk.

The sportsman’s story and thus this film are incomplete. Whereas Kapadia’s previous subjects, Senna and Amy, were thwarted at the height of their accomplishments, Maradona still lives – adrift, burdened by compulsion, but alive. This produces a strange waywardness in the closing act, as his Napoli dream finally sours. There’s a selection of handpicked coda: he breaks down on TV about his addiction; he finally acknowledges and meets his son. These omit his spell as Argentina manager and cocaine-fuelled appearance in Russia. His drug scandal at USA 1994 is a cursory allusion. That his fortunes have fluctuated fails to be depicted.

Football has always had a bizarre, insulated relationship with its morality. Players are built up as role models, before being brought low, cast out as pariahs. Behaviour – on and off the pitch – becomes an indicator of either disgrace or class. The media plays some role in these characterisations but there festers a popular public appetite for rise and fall, ascent and decline.

Redemption jostles with comeuppance, these narratives functioning in response to the age of football scientism, the smothering of the game’s great intangibles with statistics. What surprises us about the diminutive Argentinian who eventually succeeded Maradona as the best player in the world? Two things: his success is measured by number; aside from his gift, he’s basically normal.

Joseph Owen

Diego Maradona does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Watch the trailer for Diego Maradona here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS