Adam

Maryam Touzani’s Adam has a sledgehammer of a title but prefers a considered approach to origins and new beginnings. Inner-city Casablanca is not quite the blissful Eden, more a place of inhibitions, of custom, tradition and obligation. Together, two women must negotiate the dogmatic terrain through either subservience or subversion. Their relationship is defined by several conundrums: whether grief is impermanent, whether life is worth nurturing and whether the weight of society’s expectations can be managed, alleviated.

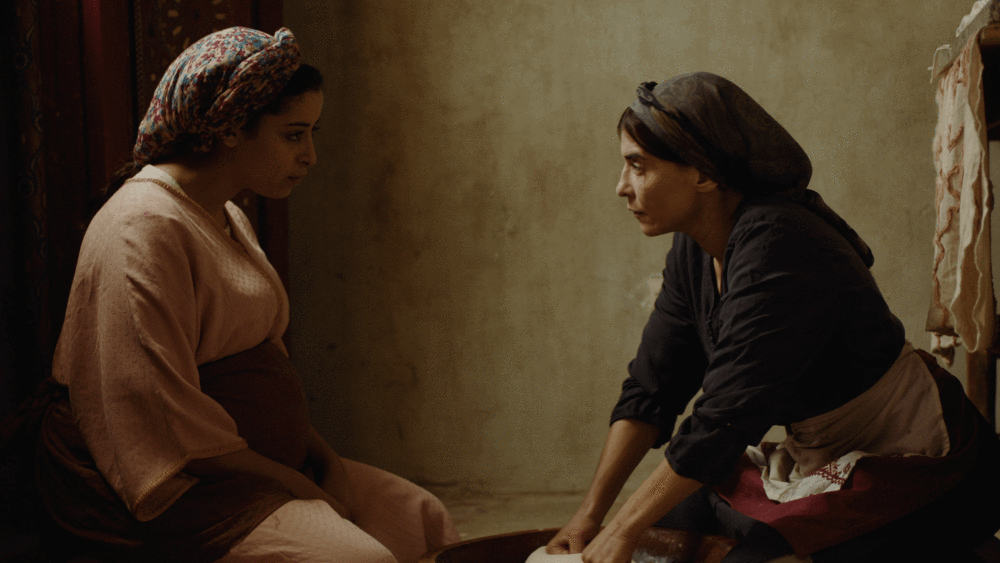

Unmarried Samia (Nisrin Erradi) is heavily pregnant, shattered and desperate for shelter. Widowed Abla (Lubna Azabal) runs an in-house bakery and has an 8-year-old daughter, Warda (Douae Belkhaouda). In a final industrious effort, a concession to the survival instinct, Samia asks to enter their home. Each offers a shade of personality: Abla is weary, conservative, grieving; Samia is younger, relaxed, intuitive; Warda is relentless, optimistic, untainted. The stages of aging reflect the process of being world-worn and ground down, of becoming cynical and despondent.

Both Erradi and Azabal have equal time to embody their characters, which produces both a vacillating perspective and an alternating temporal outlook. Samia looks forward with fright and uncertainty. Azabal looks back with resignation and opacity. Touzani confidently handles these performances to show the generational gap of urbanising Morocco. What unites them is the shadow of religious and cultural norms, which offer both a point of fixed identity and a pall of oppressive guilt. How to be a single woman and maintain respect? How to be free without losing yourself?

Forgotten record tapes and newfound rziza recipes pierce the sombre austerity of the small apartment. Samia and Abla develop a qualified friendship, one pushed and prodded to an established formula. External pressures are assumed, not shown dramatically or hyperbolically. Most secondary characters are polite and understanding, showing the problems faced by the pair to be structural and ingrained, rather than personal and antagonistic.

As light enters the apartment, the bakery opens up and decisions are brought to bear. Working in tandem – and the innate value of work is central to this film – provides Samia and Abla with a remembered appreciation: of crucial biological links, and of finding love on the regular. Touzani may overstate the baby naming but the shot of Samia’s hand caressing the soft and diminutive foot lingers, the symbol of implacable maternal instincts.

Joseph Owen

Adam does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Cannes Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Cannes Film Festival website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS