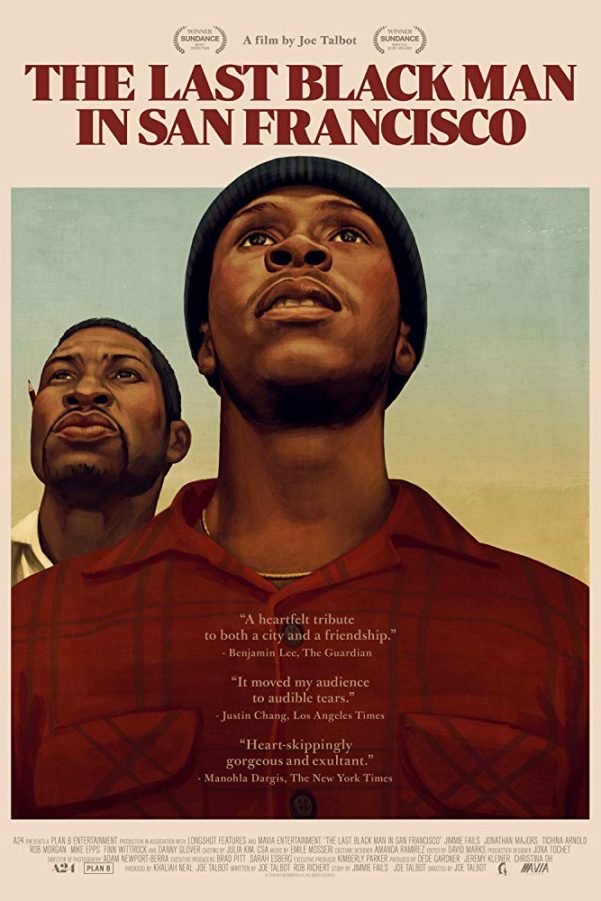

The Last Black Man in San Francisco

It’s easy to equate romance with escape, emancipation with mobility. To movement, we live in deference. Joe Talbot’s striking and consciously majestic debut feature shows the Bay Area as a centre for social and economic possibility, as an influx of white affluence into black history, as an illustration of disconcerting cultural change. To witness this, as Jimmie Fails does, is to have dramatic and theatrical visions, to cling to a fixed imaginary in a world of impermanence.

Fails plays a fictionalised version of himself, a young man in love with a classic Victorian house in the Fillmore District. It is the home in which he grew up and from which he is now disbarred, first because of its new occupants, later its prohibitive expense. With his intimate friend Mont (Jonathan Majors), Jimmie commits ad hoc restorations to the building before plunging in when the owners leave. They settle; Jimmie falls in love again. His grandfather built this house.

The residence is material and symbol, of course. Elegantly rendered woodwork suggests the beauty of the old neighbourhood. The “witch-hat” roof articulates a memory built within a memory, the architectural equivalent of oral storytelling and folklore. Within this accommodation, history bubbles up and forges a release: an exhalation, a yell, a scream. Nothing is modulated; all sounds are liberation. These men reclaim what would have been lost to inaudible market forces.

Talbot heightens this dream so as to predict tumult. The joy of possession must be tempered. Estate agents are insatiable, while Jimmie’s constructed mythos of domesticity exists on crumbling ground. A house so formally exquisite must be susceptible to subsidence. Old friends – the working-class community that remain so – form an ambivalent Greek chorus of vulnerable camaraderie and abusive chauvinism. Theatre dominates this landscape, as Mont writes and performs a play of revelation, of pointed home truths.

Actors are uniformly excellent. Donald Glover and Tichina Arnold produce subtle and uncertain figures of place and past, they the protectors of relics in bypassing currents of modernity. We feel thin investment in the characters because of the knowing sense of stage and drama, but Jimmie’s wrenching encounter on a bus lingers in desperate melancholy. His relinquishment of home is overextended and muddled, as Talbot grasps for the climactic exaltation. Just breathe, we think.

His San Francisco exists in a startling mode of euphony. Musical cues insist on a protracted state of elevation. Higher, higher, higher, the city enters delirious vertigo. Married to a stream of sumptuous images – the steep incline under the Golden Gate Bridge, the swivelling skateboard, the falling autumn – Emilie Mosseri’s score establishes ascent and descent, landing with a comic bump, the blow of a tuba. With this, it undercuts any ode to people in motion and instead acknowledges the static idea: to be stubborn, implacable, while all else is in flux.

Joseph Owen

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is released in select cinemas on 25th October 2019.

Read more reviews from our Locarno Film Festival 2019 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Locarno Film Festival website here.

Watch the trailer for The Last Black Man in San Francisco here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS