William Blake at the Tate Britain

One of the first works in the William Blake exhibition at Tate Britain is a self-portrait. Executed in monochrome, the artist presents himself with un-Blakean precision; the carefully delineated eyes stare out at the viewer with an unsettlingly powerful gaze.

Ironically, however, this is one of the only examples of copying from life in the whole exhibition. Apart from a few early drawings from his Royal Academy days, and his commercial work as an engraver of other artists’ images, William Blake (1757-1827) spent his entire artistic career exercising the power of his imagination. Although his self-portrait presents him looking out at the viewer, his best work came from within his own head.

Blake saw visions: angels, God, devils, the ghost of his dead brother, a terrifying manifestation of a flea with semi-human form. He was also a social and religious rebel, who hated slavery, contested the virginity of the Virgin Mary, and has been seen as an early advocate of free love. He defied the constraints of both the publishing industry and the art world, creating his own unique printing methods and combining poetry and images in a revolutionary way. He was both a radical and an enigma.

Unfortunately, relatively little of Blake’s fascinating personal philosophy comes through in the Tate Britain exhibition, which fails to fully convey the revolutionary nature of his words and images. For instance, it almost completely ignores the anti-establishment mythology he created over the course of his life – perhaps understandably due to its complexity, but those who know more of Blake’s poetry than his Songs of Innocence and Experience may find there’s an essential element missing.

Instead, the exhibition’s curators Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon attempt to provide a biographical framework for Blake’s life and work, firmly situating him in the world of patrons and payment; one section takes pains to explain the monetary system of the day, and shows how much Blake was paid for various pieces of engraving work.

This is undoubtedly interesting, and helps to position Blake within the context of his personal circumstances and his historical milieu, perhaps avoiding the trap of presenting him as a crazy, misunderstood poet writing alone in his attic. Instead, we are shown that Blake had a secure domestic life with his wife Catherine, who is presented as a partner in Blake’s work to a degree that hasn’t been widely noted before; she was involved in colouring his images and even posthumously finished some of his drawings.

The visionary artist-poet is described as having a “portfolio career” as a “freelancer”, mixing commercial work with his own projects. This is presumably in an attempt to make Blake’s experiences and creations feel relevant among today’s gig economy. However, the result is that the exhibition occasionally hits on a tone of dreary banality.

Despite the beauty and power and Blake’s work, the show’s focus on practicalities occasionally manages to occlude and undersell the flights of imagination and radical innovation which make the artist one of the most interesting and revolutionary creatives who ever lived.

Anna Souter

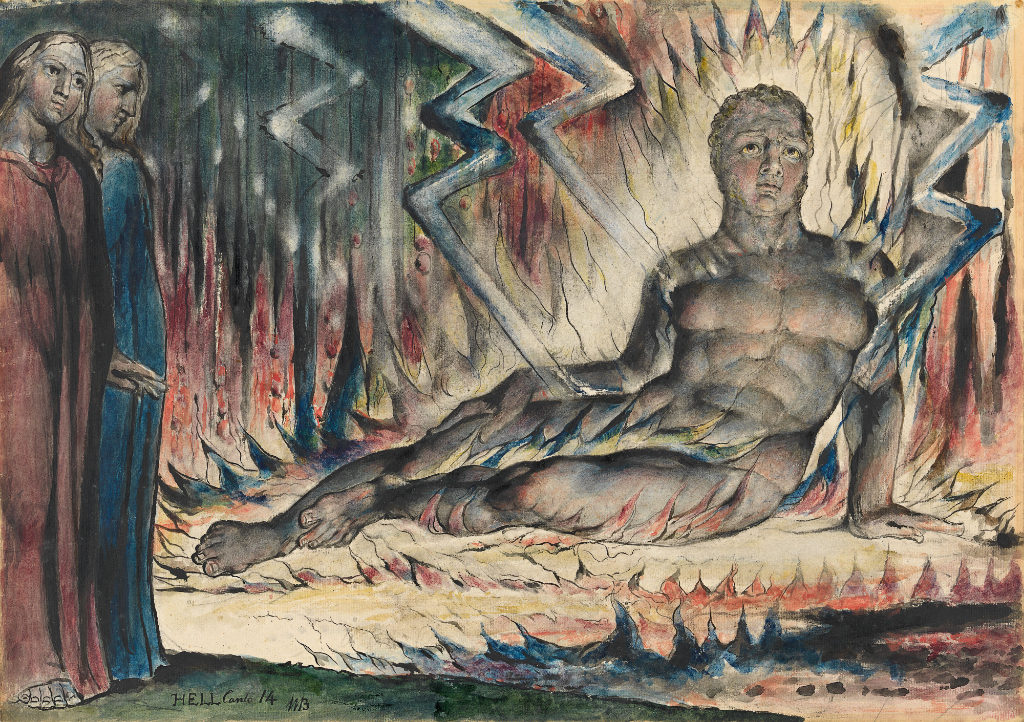

Featured image: William Blake, Capaneus the Blasphemer, 1824-1827, courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

William Blake is at the Tate Britain from 11th September until 2nd February 2020. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS