Léon Spilliaert at the Royal Academy

You can take the boy out of Ostend but he will probably come straight back. Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946) wasn’t much interested in depicting anything outside the seaside resort on the North Sea where his father was parfumier to the court of Leopold II. He came back from the Grand Tour after a fortnight. He’d seen enough.

Instead, much of Spilliaert’s time was spent in his parents’ home nursing a “stomach ailment”. The same domestic objects loom up again and again: a Bentwood chair, a large clock with an oval glass dome, his cadaverous bed.

This early Spilliaert creates an expressionistic portrait of a city if not of the dead, then of the terribly ill, of the insomniac, of the dispeptic, of the troubled. Much like Van Gogh’s, his unwell gaze turns again and again to the same subjects, becoming strange and meaningless like words repeated – and the limit of what is possible in representative art shifts.

Sometimes we feel like we have fallen through an art wormhole: Dad’s alcohol jars are painted plainly and starkly, foreshadowing pop art; a Bentwood stool is outlined with what looks like red neon, and we are in Bacon’s 1950s; the stark, black rectangle of a breakwater prefigures the minimalists.

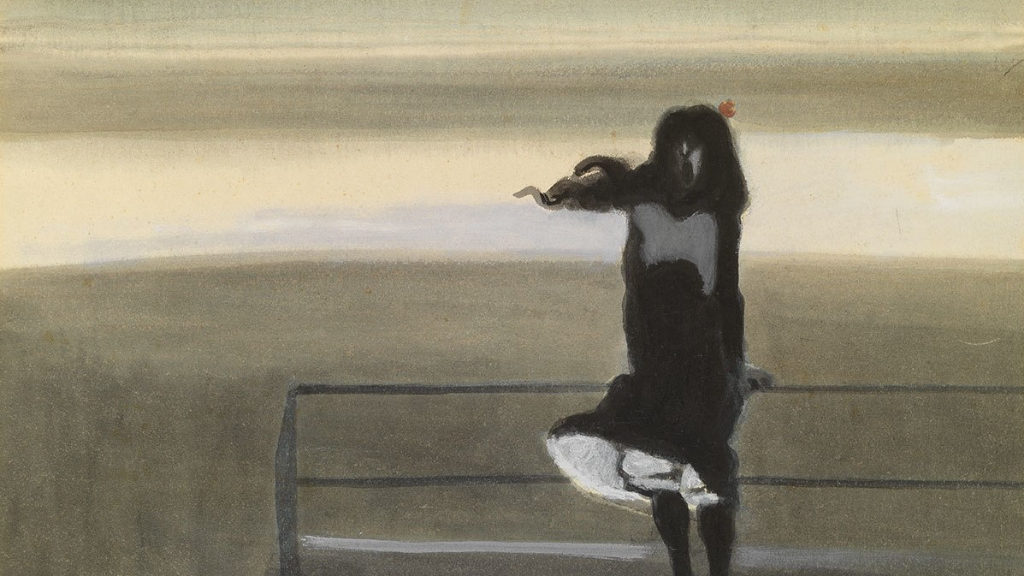

His human subjects are equally vexed: the femme fatale of The Absinthe Drinker (1907), probably an escort to the sailors of the port, whose eyes have seen so much they have become tunnels of death. The fishermen’s wives awaiting their husbands at the quayside become black blobs of worry and need. The female figure in The Gust of Wind (1904) is obviously in dialogue with Munch’s The Scream. There is a rare touch of humour in Spilliaert’s girl hollering in front of the ocean – her hair and hemline blown to right angles – and she seems to be engaged in a roaring competition with the elements.

If you have a strong objection to Indian ink, avoid this show. As if embroidering Rorschach tests, the slightly iridescent black liquid, often built up in layers like varnish, forms the dark centre of nearly every picture. Colours aren’t much brighter. You are much more likely to find monochromatism, navy blue if you’re lucky – and the odd highlight flash of muted red or yellow.

In the unquestionable highlight of the exhibition, the last two of his extraordinary self-portrait series, completed between 1907 and 1908, the ink engulfs and encircles his eyes. The skull emerges from the skin as that same glass-domed clock – becoming increasingly distorted and expressionistic – looms vertiginously behind him.

Michael Willoughby

Image: Leon Spilliaert, The Gust of Wind (1904), photo: Hugo Maertens

Léon Spilliaert is at the Royal Academy from 23rd February until 25th May 2020. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS