Malmkrog

Romanian New Wave stalwart Cristi Puiu opens Berlin’s Encounters sidebar, delivering a 200-minute philosophical rumination on the nature of war and Christianity set amongst the moral dilapidations of late 19th-century Russia. Everyone speaks in elevated French. This is unashamedly text-based cinema, although Puiu is wise enough to undercut the general seriousness and piety with elegant direction and a sharp eye for the quirks of the pompous, self-appointed intellectual elites.

Five aristocratic types hold court on God, conflict, and the vagaries of evil in a chaptered narrative that shifts emphasis onto each of the participants. The protagonists appear to be ciphers, but their characterizations emerge gradually. Nikolai (Frédéric Schulz-Richard) is arrogant and helplessly oleaginous; Olga (Marina Palii) is devout and intentionally reductive. The conversations can be difficult to follow, as the camera wanders around picking up small details: overstocked bookshelves, foregrounded candelabras, a delectable dessert left untouched. These diversions suggest something essential about human communication, the shared methods of language, the mutually agreed definitions on which understanding is based. Without these, the wheel of peace would roll over us.

Talking, talking, talking. Startling moments pierce the endless chatter: a collapse, revolution, the chimes of the clock tower, the necessary contingencies of living in the world. Concepts matter for little when the bell rings for teatime. In a belatedly introduced motif, a child plays piano and sings in an uneasy, encompassing whine. It recurs, mocking the entire company’s enterprise of grounded, reasoned postulating. International relations, laws and exceptions, the verity of the Gospels: all fall under the irony of repeating oneself, the Buñuel-inspired aporia of forlorn cross-examination.

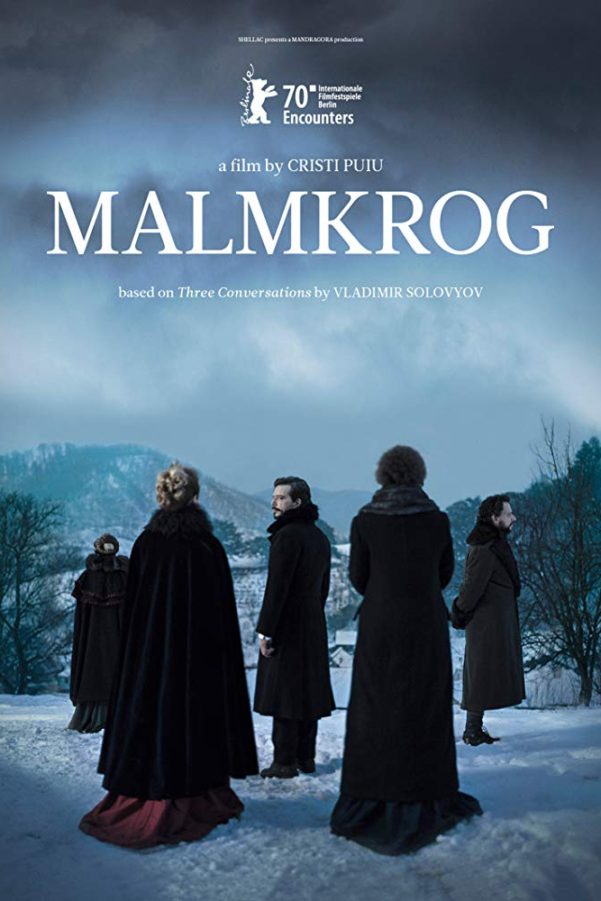

This is a devoted adaptation of Vladimir Solovyov’s semi-renowned philosophical treatise Three Conversations, and many will see it, probably fairly, as a portentous slog, an indulgent exercise in translating the timeworn strands of theological debate into extensive repetitions of highfalutin dialogue. The film has more to recommend it. Cinematographer Tudor Panduru fashions enjoyably staged tableaux, from the pristine snowy grounds that frame the first exchanges, through to imposing, close-up table discussions that amount to a sort of climax of relentless formalism. From his actors Puiu demands first-rate, physically impressive performances: there are several extended soliloquies and corresponding concentrations of expression.

Like Puiu’s previous film Sieranevada, which premiered in competition at Cannes four years ago, Malmkrog is preoccupied with domestic lives and the perverse geometries of ornate, crumbling households. This recognition of how the rich live – of how they are free to intellectualize their experiences of the world into a state of complacency – is satisfyingly offset by the almost ubiquitous silence of the servants. They tend to their masters’ needs, softly declaring dinner times while disappearing into the furnishings. Is the riddle of the film to be found in the servants? Their employers’ Dostoevsky-inspired ramblings are immaterial to their lives. They tuck in bedsheets and lay out cutlery. They are physical bodies moving in the world. That is their truth: one distinct from abstractions interminably discussed, suspended forever in the ether.

Joseph Owen

Malmkrog does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2020 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Watch the trailer for Malmkrog here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BeKXBgYUZDM

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS