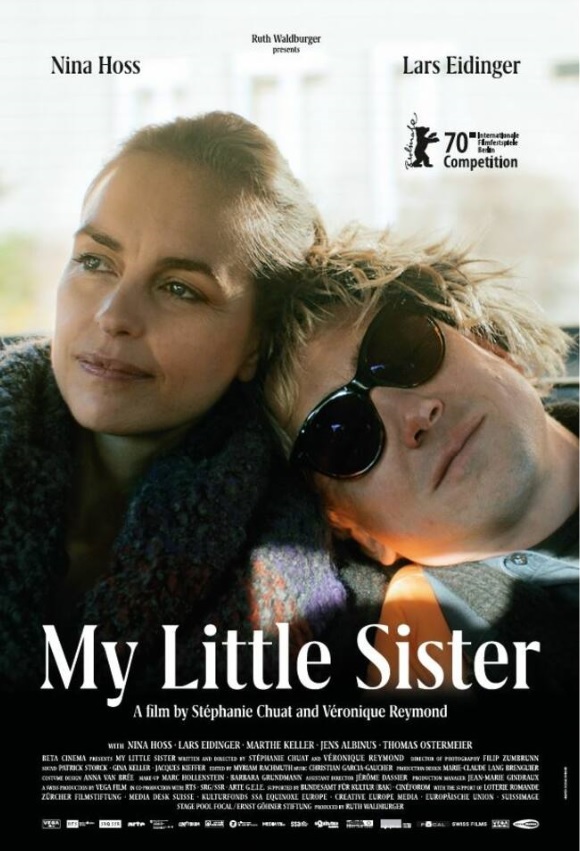

My Little Sister (Schwesterlein)

A fellow critic described this film as “relentlessly competent.” It is the sort of worthy middle-European drama commonly found on the festival circuit, the cinematic equivalent of a solemn nod. All items in the dramatic inventory are accounted for: a protracted tragedy, broad techniques of realism, the accumulation of small visual details that amass towards climax and denouement. It inspires in the viewer a bland appreciation, a desire to slow-clap a technically efficient piece of storytelling. There’s no excuse for it.

Sven (the always striking Lars Eidinger) is a relatively successful theatre actor in Berlin before he is diagnosed with leukaemia. His close relationship with his just-about younger sister Lisa (a supple performance from Nina Hoss) provides the central point from which the narrative develops. They are somewhat coyly and belatedly revealed as twins, and this explains the particularly acute connection between them. This synchronicity and reciprocation is even realised in a biophysical sense. Lisa gives Sven a bone marrow transfusion, the relative failure of which drives the plot.

There’s quite a bit of earnest literary name-dropping: characters pointedly read from “RILKE” and discuss “BRECHT”. Intertextual references abound. Sven starts out by playing Hamlet, his kingdom and constitution soon deteriorating. Lisa, a desultory playwright, uses her sibling experiences to create a Hansel and Gretel-like monologue she hopes Sven will perform. These are desperate measures just short of denial, producing a multilevelled stage of creative fictions. Within this network of reality and performance, the film offers quiet revelations about their respective lives with a consistently matter-of-fact tone and ambience.

Writer-directors Stéphanie Chuat and Véronique Reymond deploy useful variations in their scene-making: elegant conflations of diegetic and non-diegetic classical music, strategically inaudible dialogue, tactful shifts in camerawork. Unfussy transitions between character perspectives round out the subplots. Lisa’s husband (Jens Albinus) has a complex role as her immediate point of refuge and antagonism. He’s the headmaster of an elite, expensive international school in the Swiss Alps, one predicated on opulent displays of high culture and wishy-washy motivational mantras. Not so easy for him and their two children to fit into this five-act play of protracted dying.

Susan Sontag notes that with aggressive illnesses, encores are unlikely. They are certainly not bound up with one’s character or agency: “Theories that diseases are caused by mental states and can be cured by will power are always an index of how much is not understood about a disease.” This is what Lisa finally acknowledges: the brute, relentless fact of Sven’s terminal diagnosis. That middlebrow trope of the lingering portrait, capturing a subtly changing expression, shows her move from grief to acceptance, the acknowledgement that what comes with emotional loss is at least a form of residue.

Joseph Owen

My Little Sister (Schwesterlein) does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2020 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Watch a clip from My Little Sister (Schwesterlein) here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS